Festival report

3. Character observations

Moving to Mars

Of the festival’s character-based, observational docs, Mat Whitecross’s Moving to Mars: A Million Miles from Burma was a cute choice for Sheffield’s opening-night film, since it follows two Karen families (one headed by a civil engineer, one by an illiterate farmer, less propitiously) from their refugee camp over the Burmese border in Thailand to Sheffield’s grey ’city of sanctuary’, where they settle in neighbouring semis and slowly acclimatise to their new isolate urban individualism. The film was sleekly photographed and scrupulous; you just wished its patience had been rewarded with a little more acuity.

Men of the City

Mark Isaacs was more serendipitous with the shooting of his Men of the City, filming its odd quartet of City of London workers (a divorced, workaholic hedge-fund trader, a weary, chain-smoking insurance broker, an immigrant-Bangladeshi sandwich-board man and a philosophical street-sweeper) as the credit-crash broke around them. Perhaps there was less cultural distance between film-maker and subjects, but Isaacs also seemed better able to get to the hearts of his characters. In fact you felt he was most alert to what he abhorred about the world he depicted – the all-consuming mercilessness of London’s free-market human traffic. Only the street sweeper had found a way to maintain his moral equilibrium and the sense that he was contributing his work to a community.

Rough Aunties

For picking up a society’s broken pieces, though, few can be as indefatigable as the subjects of Kim Longinotto’s Sundance Grand Jury prize co-winner Rough Aunties. A mixed-race group of women in Durban, South Africa, who staff a volunteer support group for sexually abused children called Bobbi Bear, they swing from grim tragedy to ongoing calamity (a horrific roll-call of otherwise unheeded abuse cases and deaths) with amazing fortitude and not a little gallows humour. Longinotto filmed them for a mere ten weeks, but she captures the extent of their dedication and depth of their solidarity against a horrendous backdrop: a portrait of humanity at its best and worst.

Katatsumori

Intrepid women were also a theme of the third of Mark Cousins’ Doc/Fest retrospectives of the ‘golden age’ of Japanese documentaries (the 1960s and ’70s, natch), following 2007’s Noriaki Tsuchimoto programme and last year’s selection of Ogawa Shinsuke’s works. This year’s focus turned those two directors’ epic social-portrait observations on their head, focusing on the subjective selves in front of (and behind) the camera. I missed Imamura Shohei’s Madame Onboro (1970), alas, but Naomi (The Mourning Forest) Kawase’s ‘granny collection’ – Katasumori (1994), See Heaven (1995), The Setting Sun (1996) and Birth/Mother (2006) – were unsettlingly intimist, interventionist depictions of Kawase’s relationship with her ‘grandmother’ Uno (in fact her grandfather’s older sister, who adopted her after her parents’ divorce).

It’s a relationship that spans memories of Uno’s late husband, Naomi’s childhood, Uno’s ageing process and Naomi’s own procreation (Birth/Mother, most remarkably, starts with an unstinting perusal of Uno’s naked, pocked body in the bath, and ends with movingly silent footage of Naomi giving birth), and seems to be conducted entirely through the camera, whose unblimped motor is a frequent refrain on the soundtrack. The films aren’t so much ‘observational’ as ravenous for connections and contact; there’s little context, no wide or establishing shots, just long, leading close-ups, reaching out like Naomi’s occasionally visible hand.

Extreme Private Eros

Hara Kazuo’s even more intimate, ill-advised but bizarrely valiant Extreme Private Eros (1974) tries to be fly-on-the-wall, but given that the various walls are those of his headstrong ex-wife Miyuki, who has taken their son with her in search of new lovers, the uncertainty principle is writ particularly large here. “The only way to keep the relationship was to make a film,” muses the director at the beginning of the film, although there clearly wasn’t much chance for Miyuki’s next relationship, with a bar hostess, what with her ex hovering with a camera over their every exchange.

She goes slumming in Okinawa, pamphlets the local bar girls and gets Hara beaten up by gangsters, fails to adopt a mixed-race Okinawan baby, but gets pregnant by a black American G.I. and gives birth on camera, proudly unassisted. She also midwives for Hara’s sound girl Sachiko, whom he has got pregnant off-camera, and starts up a baby commune. What does Rei, their son, make of all this? Miyuki wants to raise him as “an aggressive fighter”, but alas, she laments, he’s the image of his dad, with Hara’s cowardliness and disposition to become “hysterical around her. He’s so mean…” It’s true that we see Hara weeping extravagantly at Miyuki’s assertion that she loves her G.I.; later, filming her giving birth, he’s too nervous to fix the focus, though he keeps on filming. After the screening Hara told the audience he saw himself as the film’s main character. The film was a piece of defiant self-expression in which he knew he had to show his weakness; younger self-documenting Japanese directors by contrast seem to be asking for help. (The film closed on Miyuki dancing topless at a nightclub. Those were the 1970s…)

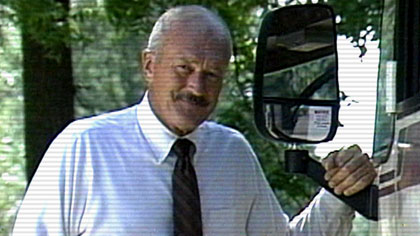

Winnebago Man

Ben Steinbauer mounted a search of a different kind in Winnebago Man, titled after the “angriest man in the world”, Jack Rebney, unwitting star of a ’90s cult video featuring foul-mouthed outtakes from a series of industrial videos Rebney had recorded working his way around a Winnebago luxury trailer. (You can see the clip reel on the film’s website.) The film was at its most fascinating offering a potted history of viral videos (and their cruelties) before and during the YouTube age. Rebney himself, a former TV journalist, turned out to be hiding with failing eyesight up a mountain in northern California; despite a strong, ongoing sense that the film was about to run out of material, Steinbauer managed to ride with Rebney to a sweet rapprochement with his unsolicited and somewhat humiliating celebrity.