Festivals

London Film Festival:

World Premiere reviews, part two

American – The Bill Hicks Story

UK 2009

Directors: Matt Harlock, Paul Thomas

110 mins

What would Bill Hicks have made of the reverence he has been held in since his death from cancer in 1994? The most iconoclastic American comedian of his generation, he has countless imitators in contemporary comedy, and has been the subject of biographies, stage shows and now even a rumoured Hollywood biopic produced by and starring Russell Crowe; yet he never broke through the American mainstream in his lifetime, while his comedy burned through such idolatry like his permanently lit cigarette.

American: The Bill Hicks Story has no intention of tearing this reputation down – it was made with the full cooperation of Hicks’ family and friends, many of whom are heard interviewed on the voiceover, with their testimonies taking the place of a single narrator – but it explodes several of the myths that have obscured reality. The portrait that emerges is of a romantic figure, despite his flaws, and a man who was intensely focused on a career as a professional comedian from a precociously young age. He was performing regularly at comedy clubs in Houston, Texas from his mid-teens. Hicks’ family granted the filmmakers access to their private archive of film footage of such performances, many of which are seen here publicly for the first time. The rage Hicks would later turn on political hypocrisy, the manipulations of those in power and other such subjects was here directed closer to home – at his family, at former girlfriends – but his brilliance is clear. The film is at its strongest when covering these early years, and is particularly good at setting us in the world of American stand-up comedy in the mid to late 1980s, when Hicks performed in Houston with his peers and friends the ‘Outlaw Comics’ – Dwight Slade, Jimmy Pineapple, Andy Huggins and others.

The film moves through Hicks’ move to L.A., his toiling on the American stand-up circuit, where he was held in huge esteem by his peers but neglected by a wider audience, the alcoholism and drug use that nearly derailed his career as promoters refused to book him (“like throwing gasoline on the fire”, as one interviewee remembers), and then the rock-star like success he achieved in the UK.

American largely avoids using talking heads, instead using a mix of archive footage, voiceover and ‘animated stills’ – a style borrowed from The Kid Stays in the Picture, the documentary about Paramount boss Robert Evans. Figures are moved from one still and placed on another, and zooms and animation are used to suggest three dimensions. It’s an ingenious approach, but at times over elaborate and distracting. The 110-minute cut premiered at the LFF feels overlong, and repetitive on some aspects of Hicks’ life (particularly when dealing with his use of psychedelic drugs – though the filmmakers do work in Hicks’ brilliant routine on a rare ‘positive LSD experience’ news story, where a young man ‘realises all matter is merely energy condensed to a slow vibration and we are all one consciousness experiencing itself subjectively… and here’s Tom with the weather’), while others (such as his relationships with girlfriends) are passed over. Nevertheless, the film gets as close to Hicks the man as we can hope for, and he emerges as an even more courageous, visionary figure as a result.

James Bell

Don’t Worry About Me

UK 2009

Director: David Morrissey

With James Brough, Helen Elizabeth

89 mins

To David Morrissey’s credit, it’s nigh-on impossible to imagine how his feature debut could have started life on stage. The lead actors from (and writers of) the original play The Pool may reprise their roles in this cinematic adaptation, but it’s Morrissey’s home town of Liverpool that’s the film’s real star. “Show me the sights”, cajoles James Brough’s Essex wideboy David of reluctant local lass Tina (Helen Elizabeth) at their initial meet-cute; and that’s precisely what Morrissey does, skipping clichéd images of Liver birds and the Walker Art Gallery in favour of the city’s more contemporary landmarks: the chrome and glass structures of the recently revived centre, dirty white turrets of the Catholic Cathedral and haunting, desolate vision of Antony Gormley’s Another Place project, its 100 life-size iron figures spread along three kilometres of the Sefton foreshore providing the film’s most indelible imagery, as well as an analogy for the characters’ overwhelming isolation.

With cheeky wag David having convinced the wary Tina to bunk off her betting-shop job for a tour of the, the two strangers stroll its streets and shores while swapping stories. Essentially Before Sunrise set in Scouseland, the film builds a bittersweet romance, the relationship reaching a dramatic climax of sorts in a confessional booth in the Cathedral. But despite some beautifully shimmering, shadowy imagery elicited from the dividing mesh, it’s here that the story’s stage roots sadly break through its surface: without the city’s sleek but seedy settings to support them, the exposed actors start to struggle, and while Elizabeth just manages to pull off a moving performance as a girl-woman brought to her knees by life’s injustices, Brough’s glib, theatrical posturing throws the film off-kilter. As Don’t Worry About Me reaches its melancholy conclusion, one can’t help but feel Tina’s had less of a brief encounter, and more of a lucky escape.

Catherine Wheatley

Have You Heard from Johannesburg: The Bottom Line

USA 2009

Director: Connie Field

90 mins

Apartheid-era was a morally bankrupt regime, but it was hard-nosed economic pressure as much as appeals to international justice that finally ended white rule. That's the argument persuasively advanced in Connie Field’s stirring and meticulous documentary, a feature-length version of one of a series of seven television films that she’s made on the anti-apartheid struggle.

The Bottom Line focuses on the long attempt by activists outside of South Africa to persuade foreign companies to withdraw from the country. It sticks to the conventions of television documentary about recent history, mixing archive footage with talking-head contributions from campaigners and business leaders, but the footage is well chosen (notably, excerpts from a slick PR assault by the South African foreign office on the virtues of ‘separate development’) and assembled with a clear and compelling narrative drive. The emphasis is on the small-scale protest groups ranged against far greater corporations, like the two Polaroid employees who exposed their company's profiteering from the South African government's compulsory ID scheme for all its black citizens, or the UK student groups who boycotted Barclays. One interviewee sums up the story as that of a mouse claiming victory over the elephant, and it has clearly been inspirational for subsequent campaigns against global injustices.

Ed Lawrenson

An Organisation of Dreams

UK/France 2009

Director: Ken McMullen

With Bernard Stiegler, Gabriella Wright, Dominique Pinon

90 mins

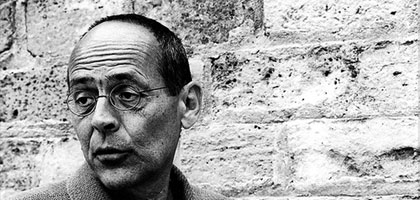

Experimental British director Ken McMullen’s latest is a fiction-essay hybrid, a fiercely ambitious, wide-ranging meditation on cinema as dream machine and political weapon, set predominantly in Paris and scored by Michael Nyman. It’s also an occasionally awkward assemblage of elements. There’s Dominique Pinon’s ponderous investigator, trailing a beautiful young journalist-actress who is obsessed with discovering if cinema can be dangerous – a question she puts to French philosopher Bernard Stiegler (as himself), recording him on a Nagra as he fires off aperçus on cinema, dreams and the unconscious. Another young couple turn New Wave-style tricks round the city, while on some faraway coastline their incarcerated activist father intones shards of Shakespearean verse-wisdom. The whole film is broken up into sections bearing one-word titles and an apposite quote: references to Derrida, Freud, Godard, May 1968 and more abound.

McMullen seems bent on creating his own deconstructive and ‘dangerous’ cinema, throwing in meta-narrative, reflexive games and repeated disruptions of the image to undermine the investigator’s attempt to 'fix' meanings. But too often Stiegler’s insights come across as banal or sweeping – philosophy for beginners – and the attempt to embed those ideas cinematically feels stilted, self-conscious rather than unconscious, other perhaps than in one peculiar scene on a Parisian rooftop. There’s also a curiously flat quality to the image, a fatal lack of energy and charge. A playful scene on a Seine tourist boat stands out: bathed in an uncharacteristically miraculous, silvery light, it nudges the film for once into a more mysterious realm.

Kieron Corless