Left On The Shelf

Mark Kermode questions the BBFC's 'new openness'

While explicit foreign-language films such as Romance, Ai no corrida, Saló and Baise-moi may be reaping the benefits of the BBFC's alleged 'new openness', the UK distributor of Wes Craven's comparatively mild 70s slasher classic The Last House on the Left believes little has changed when it comes to cutting and banning English-language films dealing with similarly controversial themes. A recent decision to continue to outlaw the American indie pic has angered and confused distributor Blue Underground, which currently holds UK rights to Craven's directorial debut. According to spokesman Carl Daft, 'The recent precedents set by Baise-moi and Saló, coupled with the BBFC's dogged insistence on substantially cutting The Last House on the Left, clearly demonstrate that the BBFC is still looking upon foreign-language films with an inherent bias.' The board disagrees. 'We make no distinction between foreign-language films and English-language films,' says the BBFC's head of press and publicity Sue Clark. 'It's the content of the film which concerns us, not the language spoken.'

At the centre of the furore are the apparent randomness of the BBFC's attitude to graphic depictions of sexual violence and the suggestion that it is more lenient towards subtitled (or 'arthouse') fare. According to the board, its guidelines don't distinguish between mainstream and arthouse films, but decree simply that 'where the portrayal eroticises sexual assault, cuts are likely to be required.' The exact definition of 'eroticised' assault, of course, remains vague. Pasolini's Saló, in which victims are stripped, raped, whipped and forced to eat excrement for a large part of the film's running time, was recently passed uncut under the strict provisions of the Video Recordings Act (VRA). For the cinema release of Baise-moi, which like The Last House on the Left has a rape-revenge narrative, a single 10-second close-up of vaginal penetration was removed from a lengthy rape sequence which otherwise retains its explicit depiction of sexual violation and humiliation. Although The Last House on the Left contains no such hardcore sexual imagery, and its scenes of sexual humiliation are cumulatively shorter than those in Saló, the BBFC has demanded that approximately nine times as much material be removed from Craven's film as from Baise-moi before cinema classification can be considered.

The Last House on the Left was first refused a UK cinema certificate by the BBFC in July 1974. Last year the board again decreed it to be 'not suitable for cinema exhibition' following a resubmission by the Feature Film Company. According to a BBFC press release dated February 2000, the distributor declined to accept 'cuts to remove images of the horrific stripping, rape and knife murder of two women' - cuts totalling around 90 seconds which would have made the film virtually unmarketable to the completist horror aficionados who constitute its core audience. The subsequent radical overhaul of BBFC guidelines unveiled in September 2000 has apparently made no difference to the board's demands for cuts which were reaffirmed as recently as April 2001 by BBFC director Robin Duval.

In the wake of the February 2000 ban, Feature dropped The Last House on the Left, which was picked up by Exploited Films, a subsidiary of Blue Underground. Blue Underground then toured an uncut print around Britain without a BBFC certificate, as had been done with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. The response was surprisingly favourable, with official approval coming from various local councils including Southampton, which granted The Last House on the Left its own uncut '18' certificate on 30 April 2001. On the same day, Duval wrote to Blue Underground restating his commitment to outlawing the film on the grounds that it contained 'gross violence committed against women, often in a context with clear sexual overtones. It invites the viewer to relish the detail of the violence and killings.' Daft disagrees: 'The BBFC's interpretation of The Last House on the Left as 'erotic' would appear to be quite unique. Reviewers over the years have invariably referred to the cold, flat, dispassionate style of the film-making - quite the opposite of 'erotica' in fact.' Nor is there any suggestion that the victims in The Last House on the Left either incite or enjoy their ordeal, a trait responsible for the video banning of Sam Peckinpah's Straw Dogs, another comparatively discreet English-language title.

Nevertheless, the BBFC remains adamant that there is no comparison to be made between The Last House on the Left and Baise-moi or Saló, and therefore no case for claiming 'precedent'. According to Clark, 'It is important to point out the difference in the nature of the violence being presented. The Last House on the Left contains three graphic rape scenes involving knives used on naked women: stripping a woman at knife-point, disembowelling a woman after raping her and knife cuts to a woman's chest during rape. The single rape scene in Baise-moi contains no weapons, but was cut nevertheless, and the violence in Saló does not contain this level of graphic and bloody violence. The Board is particularly concerned about the use of knives, which are common weapons.'

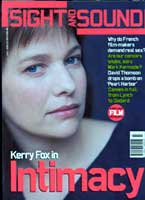

Nor does the BBFC concede any inconsistency between its treatment of English- and foreign-language films. 'It may seem that mainstream foreign language films have been passed with little or no interference,' says Clark, 'but that is only because there have been no English-language equivalents, until Intimacy.' At present the only course left open to Blue Underground seems to be to submit The Last House on the Left for video classification and - following an inevitable rejection - to take their case to the Video Appeals Committee. In the meantime, Daft remains defiant: 'Blue Underground will continue to push for the release of The Last House on the Left in an uncut form,' he says, 'unless or until the board openly admits the bias still forms part of its decision-making process.'