Last Tango In Lewisham

Last Tango in Lewisham

By Richard Falcon

In 1973 Norman Mailer sat in a crammed New York cinema anticipating what Pauline Kael had described as 'the most powerfully erotic and most liberating movie ever made' - Bernardo Bertolucci's Last Tango in Paris. As Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider rolled apart after their first carnal bout as anonymous lovers, Mailer's enthusiasm turned to disappointment: 'A marvellous scene, as good as a passionate kiss in real life then not so good,' he writes with a connoisseur's literalism, 'because there has been no shot of Brando going up Schneider.' Last Tango was for Mailer a failure as a film about sex but a potent display of Brando's soul-baring improvisations, Brando flying solo with Schneider almost as a prop. It was 'a fuck film without a fuck - like a Western without the horses.'

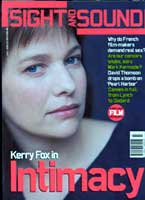

2001: French director Patrice Chéreau's Intimacy/ Intimité, an adaptation of themes and motifs from recent fiction by Hanif Kureishi, returns questions of explicit screen sex, performance and raw improvisation to the cultural agenda. Two hugely talented mainstream performers - New Zealand-born Kerry Fox and Shakespearean actor Mark Rylance (artistic director of the Globe Theatre, whose intense performance in the BBC film The Grass Arena recommended him to Chéreau) - enact a premise with echoes of Bertolucci's arthouse succès de scandale. Claire (whom we later discover to be the working-class wife of a taxi driver and an aspiring actress in her mid thirties) and Jay (a 40-ish head barman separated from his wife and children) have found themselves meeting every Wednesday in his comfortless basement flat in New Cross for sex and nothing else. No names, conversation, personal history - just sex. A film about the very 70s notion of the 'zipless fuck', Intimacy should by rights be something of a retro experience, aspiring perhaps to a neo-Reichian liberation for the characters on screen or for audiences exposed to what the pages of various British newspapers have stopwatched at 35 minutes of explicit screen sex, including the first brief shot of a serious actor fellating her co-star.

It is the latest in a series of mainly arthouse movies which have included shots of sexual penetration but which otherwise have little in common. The sequences that bind them together in this rapidly growing club fulfil different functions in each film: empty provocation in Lars von Trier's The Idiots (1998), camp retro exhibitionism in François Ozon's Sitcom (1997), hardcore pornography quoted as an index of nihilistic despair in Gaspar Noé's Seul contre tous (1998), punk shock tactic in Virginie Despentes' Baise-moi (2000), eroticism rooted in a young woman's quest for a viable sexual identity in Catherine Breillat's Romance (1999). Unlike all of these, but like a series of films waiting in the wings - including Wayne Wang's The Center of the World and Jonathon Teplitzky's Better Than Sex - the sex act itself is central to Intimacy's concerns. For all the dismay, though, that might creep into our sceptical British souls at the observation that Intimacy is a film that takes sex seriously, it feels against the odds very much a contemporary text. The camera's fixation on the bodies of Fox and Rylance as they use them to convey suffering, need and ecstasy in equal measure is troubled and disturbing. Its unswerving gaze takes on elements of a philosophical enquiry, which calls to mind the blunt suffering bodies of La Vie de Jésus. It probes intransigent issues about where performance begins and ends - in relationships, in the theatre, in the cinema.

Intimacy breaks down conventionally into three contrasting acts, of which the first, which contains most of the sex scenes, is, remarkably, the most impressive. It opens with Eric Gautier's restless camera roving in extreme close-up over the body of Jay as he sleeps on the battered sofa of his dingy basement flat. Verging on abstraction in its examination of the surface of his clothes and his flesh, this opening situates us, with a nervous determination, in potentially uncomfortable proximity to the performer's physical presence. It proposes a notion of a cinema as inescapably claustrophobic as pub theatre or as people pressed together on a train or bus. Chéreau, a talented theatre director for much of his career, is more concerned in these early stages with the body as a means of non-verbal communication than with eroticism, and this play of proxemics persists through the scenes that follow. We are up close and personal with Rylance at the start, as we shortly will be with Fox - the camera is going to pull back, but Chéreau's not going to let us get much further away.

Jay awakes with a start as Claire arrives at the battered front door. Conversation between them is stilted and tentative, but initially the Clash's 'London Calling' is high on the soundtrack. (Chéreau, sensitive to the musical enthusiasms of Kureishi's heroes, assembles a resonant mix that includes Bowie and Iggy Pop.) Claire uses a question about Jay's boxes of CDs to ease the transition into the flat, where he makes her a cup of instant coffee. As he tries to tidy the mess in the barely furnished room, he turns off the music and there's a charged and awkward silence. She stands above him and her hand reaches into the frame to touch his face and neck. It's a tender gesture which moves from pity then almost benediction through to desire, and on a rapid cut they are clawing at each other's clothes and then clumsily undressing side by side on the blanket strewn over the dirty carpet.

What follows is a sequence of urgent real-time sex in which the details - of pitilessly lit, vulnerable pallid flesh, of the condom hanging limply on Jay's penis as they disengage, of her reassurance to him after he has lost control too quickly - owe little to any recognisable tradition of filming sex for the screen. It's a painful sequence, conveying a powerful sense of need and desperation and wordless confession, as squalid and only as apparently artless as Tracey Emin's unmade bed. The performers' flesh is as candidly exposed as that of the figures in the paintings of Lucian Freud. (Freud and Francis Bacon were both artists discussed by Chéreau and Kureishi, reminding us that Bertolucci prefaced Last Tango with Bacon's 1964 portrait of his fellow artist.) There will during the course of the film be no less than five more scenes of sex between this couple. Resolutely non-pornographic despite their detail, each subtly illustrates through performance, editing and mise en scène the different meanings this act could have for these characters as their loose arrangement grows inevitably into a relationship - the fourth, for instance, embodies a mute act of betrayal on the part of Jay after he has uncovered Claire's home life.

The novella which gives the film its title is a tough gig for an adaptor. Ironically its Jay is not a barman but a writer who straightens out literary narratives for films, 'turning gold into dross' and making a good living in the process. ('If only writers had seen in the past that all written stories would be translated to the screen,' he laments.) It follows Jay's contradictory thoughts and the disorderly emotions to which they are in thrall on the night he has resolved to walk out on his wife Susan and their two small boys after 10 years of marriage. This interior monologue runs on a rich mixture of self-pity, self-loathing and self-justification. It is at its most shameless in its denigration of his wife, seen as efficient and bustling, with a 'hard, charmless carapace' - a woman too superficial to lapse into 'inner chaos' like Jay, whose 'fat red weeping face' during their attempts at marital therapy disgust him as does her claim to be a feminist when 'she is just angry.' (Kureishi had, famously, abandoned his own wife and children, and an unusual degree of controversy clustered around the novella's alleged lack of aesthetic distance - members of his own family even condemned him in the British press for publishing it.)

Depending on your perspective, Jay is an unreliable narrator - we are called on to supply our own moral perspective around the edges of the outpourings of his unquiet mind - or Kureishi is an unreliable novelist, placing the 'truth' of his own perspective on marriage, the unhappy realities of male middle age and the necessity of being true to one's own desires above common decency and the demands of literary construction. What is undeniable, though, is that Kureishi's vivid, accomplished and at times chafing and raw prose makes for intense and very uncomfortable reading. Jay is leaving out of boredom - he wants back the passion and relish of life which he remembers from his youth. He wants the intensity of romantic love - without which 'most of life remains concealed.'

Sex - along with drugs and rock and roll - has long been central to Kureishi's conception of the creative metropolitan boho life. A major climax of his screenplay for Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1987) - a film initially to be called The Fuck - is a split-screen sex scene involving the eponymous married couple and their respective lovers. In the novella Intimacy, sex with his lover Nina is the reward Jay holds out to himself at the end of the terrible night when he walks out. 'There are some fucks,' Kureishi has Jay pronounce with unwelcome and more than debatable candour, 'for which a person would have their partner and children drown in a freezing sea.' Life alone in a dank London flat, however - the existence being lived by the film's Jay and already lived in the novella by his frazzled friend Victor (Alastair Galbraith in the movie, first seen soaked in a stupendous drugs sweat) - may offer sexual opportunity, but in a cod-Freudian image worthy of Nabokov, also proffers the plate of saveloy and pickled onions in front of the television. Men behaving badly, dreaming of a life ungoverned by the orderliness of women while being driven forward by their bodies as blank canvases for their own desires and needs, were already caricatured by Kureishi in Sammy and Rosie get Laid, when during Rosie's absence Sammy tries to eat a hamburger, smoke a joint and masturbate all at the same time. The novella's most morosely difficult moment for the squeamish reader invokes just such a loosing of the male id, by having Jay masturbate furiously at the bathroom sink over his wife's knickers, and being disturbed after he has climaxed by his son who has just soiled his pyjamas.

Chéreau and his co-scriptwriter Anne-Louise Trividic retain this scene - giving Rylance the opportunity to go for gold as a kind of homegrown Harvey Keitel. Further scenes from Intimacy the novella appear in the film in two intensely brooding flashbacks and in verbal references to Jay's separation. The anonymous Wednesday liaison comes from the story Nightlight in Kureishi's collection Love in a Blue Time - a spare, elegant afterword almost to Intimacy. 'There are few creatures more despised,' the anonymous narrator tells us, bereft with self-pity, 'than a middle-aged man with strong desires.' Like Jay, this narrator has walked out on his family, and his meetings for sex with an anonymous woman who chooses to return each week for reasons he cannot fathom are his way of reassuring himself he is still alive, allowing him to 'reach beyond himself into the world, finger by finger.'

For Chéreau, 'Nightlight' was the key that opened up the world of Intimacy - the narrator here is holding on to his weekly sexual meetings as a hope of redemption, to edge him out of despair. The story is every bit as eloquent as the novella on the subject of male mid-life malaise, but its grief-stricken tone resists the provocations of its amoral ending, in which the narrator is free to be with his younger lover and is accorded a moment of grace in which - in terms that recall a consequence-free spin on the pact Faust struck with Mephistopheles - 'the best of everything accumulates in the moment.' Nightlight lends itself more to the unforgiving gaze of the movie camera, perhaps, because it is less self-deluding, but the narrative is still locked inside the tortured mind of its male narrator.

As with Chéreau's earlier Those Who Love Me Can Take the Train (Ceux qui m'aiment prendront le train, 1998), the most powerful parts of Intimacy tend to refuse exposition as a hindrance to improvisation and immediacy - precisely those qualities in life and art that Kureishi's protagonists hanker after. Where Kureishi's prose picks at Jay's psychic sores, Chéreau and Trividic's two flashbacks invoke the novella largely through iconic detail presented as emotional memory rather than backstory. We see Jay taking the signed John Lennon photograph from his study as his only keepsake, we see his children's shoes in the hallway, and Jay bathing them. We hear his son's heartrending sudden burst of childish enthusiasm for the world ('Daddy, I love everybody') and glimpse his wife Susan as she realises what's happening. These flashbacks recall the most emotionally incisive moments of the novella, making Chéreau's movie a rare adaptation - a film that's more resonant the more familiar you are with the Kureishi stories. Where it becomes too expository - in the final section and in a sequence where Jay sleeps with a giggling young woman he meets while rescuing Victor from a drugs party (taken from another Kureishi story, D'accord, Baby) - it is in danger of sliding into cliché and occasionally muddle. Chéreau himself seems to realise this: a third, talkier flashback (downloadable from the film's French website) which imports fully a sequence towards the end of the novella when Jay is attacked while trying to pick up a young woman at a club was removed from the release version.

Chéreau's upfront presentation of his protagonists' sexual encounters would once have run into problems with the BBFC - particularly as this is a film which could play in mainstream venues rather than in the arthouse ghetto where sexual explicitness is increasingly taken as read. According to research by the censors, though, explicit sex in the cinema isn't something that concerns the British public. Whether this is due to apathy, or to a genuine cultural or generational shift, or to the nature of the BBFC's research is beside the point - it looks as if the history of screen sex in the UK will be increasingly separated from the history of screen censorship. But as the BBFC's press spokesperson revealed to a Observer reporter, there are still nagging doubts: 'If it's in English,' she said, 'with people you recognise and bus routes you recognise, possibly, you become more involved with the film and might find it [i.e. the sex] more startling.' The comment about bus routes is particularly perceptive with regard to Intimacy's second act, as Jay decides to follow Claire through the streets and Chéreau reveals a fondness for London transport which redefines our notion of 'the red bus movie'. Jay follows Claire first by train to the pub where in the basement theatre she is performing as Laura in The Glass Menagerie. He discovers that she is married to a taxi driver (Timothy Spall) and has a small boy. On his second attempt to follow her he loses her in the West End and jumps on a number 23 to Ladbroke Grove. Claire has, with some delight, turned the tables and is now stalking him until she realises when he makes his way to the pub, with her husband's taxi parked outside, that he knows about her family. It's a pivotal scene - the hero stalks his romantic obsession through the city streets, Hitchcock's Vertigo recast in British naturalistic mode taking in the non-tourist London that is Mike Leigh territory: Lewisham Way, the Elephant & Castle and a bus route that leads to Timothy Spall playing pool in a pub.

As Chéreau and DoP Eric Gautier open the film out on to the London streets, we remember with a jolt that Kureishi in the 80s provided us with some of the most vivid images of the city - a suburban dream of a metropolis alive with possibilities for the bohemian and the carnivalesque, and to dust off two period adjectives, the alternative and the oppositional. In My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) Kureishi and Stephen Frears used the streets of South London to turn Thatcherite entrepreneurialism on its head, embracing a vision of multiculturalism and sexual freedom whose unexpected popularity defined a moment in British film's relationship with the city. In Sammy and Rosie Get Laid London took in an apocalyptic wasteland where the protagonists moved with easy aplomb through streets ablaze with riots resulting from the divisive politics of the decade. It was a resonant but resolutely fictional view. For all the 'searingly indicted' social injustice, Kureishi was clearly jazzed by the city as a site for the realisation of fantasies of bohemian self-fulfilment. The turning point, perhaps, was his disappointing directorial debut London Kills Me (1991), which transferred this take on the capital to the 90s and offered a compendium of sex, drugs and rock-and-roll alternative lifestyles which now looks as dated as Dock Green.

In Intimacy the novella Jay approaches the millennium with few hopes or ideals and is given to periodic musings about his generation. The beneficiaries of the hard-won freedoms of the 60s, they are defined as a contradictory bunch: both obsessed by 'music, dancing and conscienceless fucking' and 'an earnest and moral generation' who 'held back the Labour Party with their ideological obsessions.' Only the fucking appears retrievable for Kureishi's heroes now, and their London is 'a city of love vampires, going from person to person, looking for the one who will make a difference.' Chéreau's vision, red buses apart, owes little to the author's lost 80s metrocentric fantasia. The squalid interiors of Jay's and Victor's run-down flats might be a product of Kureishi's heroes' desire for dingy decadence and nihilistic chic, but the cramped and graffiti-covered streets Jay moves through convey a desolation beyond fashion - and defiantly a long way from Cool Britannia.

Chéreau's film is at its weakest as it becomes more dependent on dialogue. When Rylance's Jay spitefully goads Spall's cuckolded husband Andy with stories about his 'Wednesday fuck', there's an awkwardness to the exchanges, despite Spall bringing an edge to an unenviable role. The idiom is occasionally forced - 'Call me a wanker if you like, but I'm a pig in shit' is Andy's defiant summation of his marriage, which makes you wonder whether French offers better options for upfront verbal sparring around infidelity. (It's a thought soon squashed by the presence of young gay French barman Ian, whose occasional bursts of sagacity seem to come from a more hopeful but less convincing place.) Both Claire and Andy are conceived of, without a trace of patronage, as superficially 'ordinary' by Chéreau and Trividic - as if it takes a French director not to patronise the everyday quiet desperation of a character like Andy, whose anguish at the realisation of what is happening is vivid and affecting. Running alongside these scenes is what we are allowed to discover about Claire - her night-school acting class and her growing relationship with one of her older students, Betty (Marianne Faithfull), to whom she divulges details of her affair.

Both these female characters are the creations of Chéreau and Trividic, and as their film moves to its conclusion it becomes clear that the film-makers have shifted the emphasis from the claustrophobic self-pity of Kureishi's male egos to the female side of this heterosexual equation. As Claire breaks down as a tattooed youth improvises passion with Betty in her acting class, we realise that her desires and needs matter to the film-makers as much if not more than Jay's. In the novella Jay the writer justifies his sexual bad faith by his need to live a full and creative life - an old song. In the film Jay is a barman in a horrific trendy watering hole and Claire is the one with the creative impulse, even if her reach is seen to exceed her grasp. In one of a series of fever-pitch emotional confrontations played out in conspicuously self-conscious gallic mode in the tiny empty pub theatre, Chéreau's Jay berates her, verbalising his unspoken demands of their Wednesday meetings: he thought she could teach him, that she was 'ahead of him and would tell him what she knew.' On the other edge of the triangle, Andy at the height of the row following his discovery of her infidelity tells her that she 'will never be an actress.' Her response is that he doesn't even know how to hurt her: for Claire acting is about self-realisation; she's testing the boundaries of improvisation, investigating the meaning of a life fully lived against the constraints of the everyday, using it to fight the pain and to combat a defective self-esteem, ubiquitous in the film and the world of Kureishi's fiction, as in British life.

Chéreau here is finally according to her the motivation which in the novella is Jay's. Their sex was about her wanting to start feeling again, forcing her to embrace life. When we see Claire disappearing on to a bus in the busy South London street after it has all ended, it is her needs, desires and existential crisis that a gay French director and a female co-scriptwriter have lodged in our minds. Kerry Fox's achievement here is particularly marked. After a century in which the cinema has been the vehicle for men - Brando, for instance, in the medium's most famous testament to middle-aged anguish, the impossibility of divorcing sex from emotion and the performance from the performer - to bare their souls in virtuoso solos using the instrument of women's bodies, Fox's superb incarnation of Claire is a timely reminder that it really does take two to tango. In Mailer's terms, she has made a valiant effort to give the Western back its horses.

Braving out the explicit

Having won the Best Actress prize at the Berlin Film Festival for her role in Patrice Chéreau's Intimacy, New Zealand-born actress Kerry Fox admits, 'I've no idea where to go next.' When we met in London to discuss her sexually raw and emotionally unbridled performance, she had her mother at her side and her 11-week-old son at her feet.

Chris Darke: How did you come to be involved in Intimacy?

Kerry Fox: I met Patrice Chéreau months before we started shooting. I didn't know who he was or what the meeting was going to be about. I hadn't seen a script, so I had no preconceived ideas. He tried to be as explicit as possible and to gauge my reaction to the mention of the sex. I tried to brave it out and we talked about how we'd never seen a film like that and that it would be good to do an extremely truthful picture about a sexual relationship, about how you become intimate with someone else.

How did you go about building Claire as a character?

I got a lot of cues from Timothy Spall, who plays her husband Andy, and from the other English people involved, including Marianne Faithfull, who plays her friend Betty. In a way her character felt historical - she had a very limited world and environment, and she'd never really done much. But I never felt I had a whole picture of her as a character. Every day I'd come to work in a state over whether I'd do the right thing by her and I spent most of the time not knowing what I was doing. Part of that was because of the way we'd agreed to play it - that I'd give myself over to Patrice and trust him completely. That was the agreement I made with myself and as a result I did work I never thought possible. I got the impression that Claire's not a very good mother. She has a very strange relationship with her son, who comes to watch her in the play every night. Then her husband is bullying and controlling but she just allows it to happen. It's a complete lack of self-confidence.

Were you able to play the sex scenes with a variety of emotional registers or was there always only one way? For instance, the penultimate time...

Ah, the rapey one. I felt quite sure of that scene. I remember that my co-star Mark Rylance found it very shocking and I knew it would be terrible to shoot. I don't think Mark realised how terrible it would be. When I look back I have the sensation I took the images from life, not necessarily from my own experiences but from other people's.

I read that Chéreau directed the sex scenes so you would know exactly where the camera would be. That they were choreographed.

They were as choreographed as any scene is. There was no handheld camerawork but you weren't sure if the camera was on your face or on your hand. Though you knew it wasn't up your bum, which was important for me! We talked a lot beforehand because we knew it could make my life very difficult and that before I went into it I would have to be incredibly clear. When I finally watched the film I was eight months pregnant and was just laughing and thinking, 'Imagine doing that now!' In the past I've held on to aspects of my characters and found it very difficult to let them go, but not with this one.

How did you and Mark prepare for those scenes?

We talked to each other about how we were directed and Patrice talked to us about how we each worked. We talked about being good to each other, and kind, open and honest. That we must always tell each other exactly how we felt. If you're working with someone as good as Mark, it makes you a better actor. When I watch him on screen I'm amazed by his work - it just seems so simple. I wish I could be like that.

How did you feel about playing a failed actress?

[Laughs] It's a very delicate area, particularly as she teaches as well. It was made easier because she has a scene where she recognises her situation and despairs. She doesn't have the desire to be a professional deep within her, and since I used to teach acting, I'd seen that. It was something I found very difficult to get out of people. Why did they come to these classes? Did they want to meet people? Did they just love to perform?

New Cross climaxes

Richard Falcon: What attracted you to Hanif Kureishi's recent stories?

Patrice Chéreau: When my co-scriptwriter Anne-Louise Trividic and I read the collection Love In a Blue Time we were attracted to a very beautiful short story 'Nightlight'. It was like an enigma - and at the end we wanted to know what happened next. So though I was initially inspired by the novella Intimacy I later put it to one side and drew inspiration from the stories.

Your film indicates the extent to which Kureishi has repeatedly delved into male mid-life crisis.

I'm not so interested in male mid-life crisis. I had dinner with Hanif two days ago and he said, 'You took a novel which was about a man, and then made a film about a woman.' The woman, Claire, didn't exist in Intimacy and in the short story she was a myth. I'm very critical of the men in the film - they make every relationship mistake possible.

You give some of the motivation of Kureishi's male narrator to Claire in that she needs the relationship to feel alive.

Somebody at Berlin said Claire behaves like a man, but that's shorthand. She has the courage to act. Men are generally more vulnerable. Marianne Faithfull told me the film shows how men are: fragile.

Mark Rylance performs this aspect brilliantly.

Jay is hooked very quickly, is in love very quickly. But for Claire it's about survival. By the end of the film they've saved each other's lives and evolved. It's the most beautiful thing you can show in a film - that people can change.

How did you achieve the sex scenes?

The reason the sex scenes are unusual is that we rehearsed them in the same way as dialogue scenes. We gave time to the actors to get used to the scene. The scenes were completely written out and the point was not to stop at the moment where films usually stop and introduce an ellipsis. If we'd cut away, paradoxically it would have been just another sex scene. But now you see the difficult attempts of two bodies to unite when these characters don't know each other. The project with my writer was to script this to the climax, until they come. Of course many performers wouldn't go along with this. There were actors who wanted to do the part but refused to follow this through, actors who might agree but who'd change their mind on set or actors who are too happy to do it! In rehearsals with Mark and Kerry I developed rules. First, the point was not to show something in particular, but also not to hide anything. Second, I wouldn't use a handheld camera as this would be voyeuristic and the actors wouldn't be able to hide from it. And the third rule was to rehearse. The actors didn't improvise in these scenes: each gesture was discussed and they knew exactly where the camera was - a matter of respect - so they could hide parts of their bodies if they wanted to.

You make good use of non-tourist London.

I wanted Gary Oldman for the film, but he wouldn't do the sex scenes. But he did help me a lot - he showed me the Old Kent Road, Peckham and so on, and then I went off and discovered New Cross for myself. I also had a great location manager.