Festival report

Annecy’s animated crowd

Cristal-winner The Lost Thing

Isabella Kaminski reports on the Annecy Animation Festival, where techniques from past, present and future meet at one forward-thinking event

Although film software, style and substance have developed dramatically in the half-century since Annecy hosted its first animation festival, the sense of anarchic fun has not diminished. Every year, thousands of children and children at heart descend on this pretty French town to throw paper planes on to cinema stages and yell at animated rabbits. But once the lights dim there is always a respectful silence for the passion, frustration and heartache that have gone into making every film screened here.

It’s a tough time for animation, with co-productions becoming increasingly common as studios chase subsidies and tax breaks around the continent. There’s no doubt that France still outstrips other European countries, due in part to the classical training in drawing and sculpture offered in its film schools, so it is unsurprising that the festival’s opening ceremony features Sylvain Chomet’s The Illusionist (L’Illusionist). Based on a script by Jacques Tati, this is a film that rightly deserves to be described as charming.

This year’s big-budget films included the fourth instalment of the unstoppable Shrek franchise and a timely screening of Toy Story 3D just before Toy Story 3 is due to be released. There was also a premiere of Pierre Coffin and Chris Renaud’s Despicable Me, a witty CG animation about a failed supervillain.

Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox ultimately picked up both the jury and audience prizes this year, with any concerns about its faithfulness to the original Dahl story overshadowed by appreciation for the animators’ technical skills.

A special distinction was also given to Eleanor's Secret (Kerity la Maison des Contes), in which a dyslexic boy has to read a magic spell in order to rescue fairytale characters from oblivion. Although it refreshingly avoids a fantastical resolution to the boy’s reading problems, the story lacks any true emotional spark and the occasional use of CG is clunky against the gentle 2D drawings.

Metropia

Much more impressive was Tarik Saleh’s Metropia, an unnerving beige-toned thriller co-written by Stig Larsson and set in a future where Europe is connected by a giant subway system. Lead animator Isak Gjertsen developed an innovative photomontage technique specifically for the film, and the distinctive-looking characters, despite their bulging eyes and distorted heads, feel and act in a recognisably human manner as they unravel a terrible conspiracy.

Anime was well represented this year by the Japanese Academy Award-winning Summer Wars, a virtual-world fantasy brought firmly down to earth by a huge cast of characters representing the protagonist’s extended family. With work of this high quality Hosoda Mamoru deserves to be considered the new Miyazaki Hayao. There was also enjoyable silliness in One Piece Film, full of crazed oversized beasts and cheesy one-liners, and the futuristic Redline, a satire about commercialised racing set in a sprawling futuristic world.

Also noteworthy was Piercing 1, which director Liu Jian sold his house to finance and which he claims is the first fully independent Chinese animation. The hand-drawn images are crude and faintly reminiscent of Beavis and Butthead, but Jian’s script tackles the kinds of social problems – theft, drugs, alienation – resonant in any small town. Piercing 1 has not yet been publicly screened in China and Jian does not know how the censors will react, but it is certainly a brave film about the brutal physical reality and emotional emptiness of modern life, and it had one woman crying in the cinema.

Just when it was all getting a bit realistic, along came The Mysterious Presages of Leon Prozak (Los extraños presagios de León Prozak), a Pythonesque montage of insane dreams and pretentious self-referentiality.

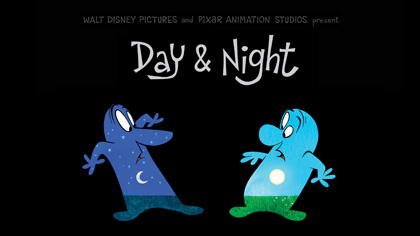

Day and Night

The short films were smart and fresh as ever, with the Annecy Cristal going to The Lost Thing, a quirky story based on a book by illustrator and writer Shaun Tan. Other highlights included Love Patate, a spud-based horror story; Recordare, an elegiac symphony of scanned images of human cadavers set to an operatic score; and Pixar’s latest short Day and Night, which layers traditional cartoon drawings over computer-generated images to excellent effect. Unfortunately the director, Teddy Newton, said it was unlikely Pixar would be experimenting with 2D animation again in the future.

Annecy has a sense of professional fun that is sorely lacking in other film festivals and a mood of collaboration that will undoubtedly lead to some great new work over the coming year. In particular, we were treated to a preview of The Flying Machine, a stop-motion and live-action adventure in which two children journey through the skies of Europe on a piano, set to a soundtrack of Chopin’s Études. Produced by Hugh Welchman (producer of Suzy Templeton’s Oscar-winning short Peter and the Wolf), the film features two appealing stop-motion characters: Anna and her geeky cousin Chip Chip, who have soft silicon faces sculpted around specially made mechanical heads, which gives them a gently naturalistic look and an astonishingly subtle range of facial movement. The film will premiere in November but its animators have yet to tackle an incredibly complex two-and-a-half-minute stop-motion sequence – apparently the longest in animation history – that will see characters dancing around a construction site as the flying machine circles above their heads, throwing up hundreds of flower petals in its wake.

Filming The Flying Machine

The true impact of 3D has been extensively debated elsewhere, but its presence is unavoidable here at Annecy, whether it is being fully embraced or subverted with deliberately flat 2D animation. However, The Flying Machine crew seem to have seriously considered how to use this new trick, designing extra-large sets to compensate for the narrowing effect of 3D.

Today’s animators have an archive spanning many decades to draw on but are keenly aware of the need to collaborate and share increasingly niche technical skills. If this festival is anything to go by – and the excellent clutch of graduation films suggests it is – the next 50 years will bring a wealth of new techniques and a generation of animators unafraid to tackle the most difficult and personal topics, as well as breathtaking flights of fantasy.

See also

Me and Joseph Brodsky: Nick Bradshaw talks to Russian animator Andrey Khrzhanovsky about his Joseph Brodsky memoir Room and a Half (online, May 2010)

Best of herd: Nick Bradshaw previews the 2010 British Animation Awards (online, February 2010)

The best online videos of 2009 (online, January 2010)

Animation: timeline from trick effects to CGI (August 2006)

Castles in the sky: Andrew Osmond on Hayao Miyazaki and Howl’s Moving Castle (October 2005)