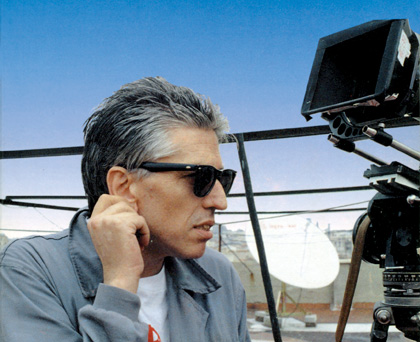

Iván Zulueta, director

b. 29/09/1943; d. 30/12/2009

With Iván Zulueta’s passing we have lost one of the few originals in modern Spanish cinema. Zulueta became a cult film-maker with his second and final film, Arrebato (1979), which follows José Sirgado (Eusebio Poncela), a hack director of horror films, as he drifts into the strange world of Pedro P. (Will More), a young amateur film-maker. Pedro shoots obsessively with a Super-8 camera in search of the right rhythm to capture the ‘pause’: a moment of suspension that leads to a state of rapture (the literal meaning of ‘arrebato’). Both men end up being literally and metaphorically devoured by cinema.

This state of rapture was something Zulueta pursued throughout his life. In his baroque imaginarium, Polaroids and children’s sticker albums amalgamated with Psycho and 1960s pop music; Welles happily co-existed with Disney and horror B movies. Zulueta thrived in the burgeoning countercultural milieu of the early-1980s Madrid movida. But unlike most film-makers in the transitional years from Franco’s dictatorship to democracy, he had travelled abroad. His exposure to the New York underground informed his numerous experimental shorts, as well as Arrebato’s bold use of found footage.

Zulueta’s fascination with the figure of the double features everywhere, from Leo es pardo (1976), his best-known short, to his late television work. Though the blue-eyed, androgynously handsome Poncela plays the director’s idealised alter ego in Arrebato, his mysterious dark twin, More’s Pedro P, haunts the film. The lonely scion of a well-to-do family, he wastes away, surrounded by childhood fetishes and Super-8 films. He’s a ghost of the first post-Francoist generation, caught between existential disenchantment and a state of emotional arrested development.

Arrebato was turned down by Cannes and Berlin, reportedly on the grounds of its explicit images of drug-taking and unapologetic intimations of suicide and homoeroticism. But the film’s subtle but pervasive influence can be traced in the work of many contemporary film-makers, especially in the new wave of Spanish horror films. When the film was released, one malicious review suggested that Zulueta’s obsessive love for cinema was unrequited. Yet his cinephilia was not mere infatuation but a way of life, which makes his untimely disappearance as a film-maker after Arrebato all the sadder.

In later years Zulueta was sustained by sporadic television assignments, while also designing film posters for Almodóvar and others. But his special place in Spanish film history is assured. Arrebato has become a bona fide object of cult cinephilia – though it still awaits an official DVD release in the UK and the US. In an era in which image saturation seems to be slowly killing off the thrill of unexpected discovery, Zulueta’s rapturous cinema haunts the screens of the digital age, waiting for its moment.

Belén Vidal