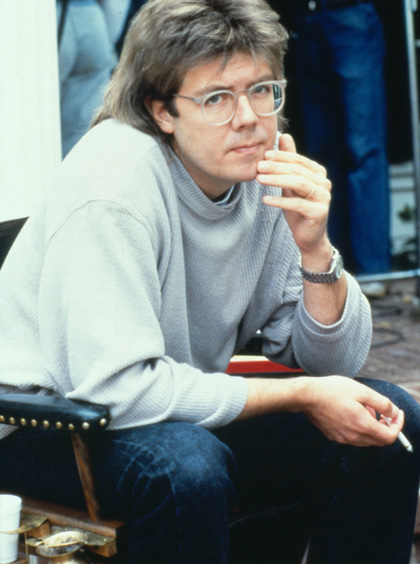

John Hughes, director

b. 19/3/1950; d. 6/8/2009

The high-school bell had rung in cinemas before John Hughes’ debut Sixteen Candles (1984), but never so convincingly. Where once Hollywood had given us immaculately coiffured twentysomethings, there were now real teenagers with their proper accessories – braces and glasses. Hughes understood the classroom to be a tribal place, and in the 1980s he obsessively catalogued the teen food chain with six comic dramas (four as writer-director, and two as writer-producer) in the space of four years.

Burrowing deep into the teenage psyche, he revealed awkwardness, longing and woe. His characters were sick of being held captive by parents who forgot their birthdays, expected too much or simply didn’t care. “I understood that the dark side of my middle-class, middle-American suburban life was not drugs, paganism or perversion. It was disappointment,” he once admitted. With his ‘yeahs’, ‘likes’ and ‘you knows’, he was the Bard of teen-speak, with a knack for both witty and philosophical one-liners. How many teenagers have watched his films with a finger on the rewind button, eager to memorise Buellerisms (“Only the meek get pinched. The bold survive”, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, 1986) or Benderisms (“Does Barry Manilow know that you raid his wardrobe?”, The Breakfast Club, 1985)? But while the boys got the best lines, the girls – squeaky introverts, flat-chested redheads or, even better, tomboys – were often the more memorable and human characters.

The majority of Hughes’ teen films were both critical and commercial successes, although critics tended to be sniffy about how his films ended – frequently with a kiss across the class and popularity divide. Hughes, who was adamant that he made films for teens not adults, would no doubt have rolled his eyes. His films were fun, escapist fantasies, where you could use your computer to create your dream girl (Weird Science, 1985), or where the school heartthrob is really after “somebody I can love, that’s gonna love me back” (Sixteen Candles). What else would you expect from a die-hard romantic who as a teenager claimed to have watched Doctor Zhivago every day during its local run?

Though forever associated with the 1980s, Hughes actually graduated in 1968 – from Glenbrook North High in Chicago’s suburbs (the facade of which you can spy in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off). Debate has always raged as to which of the teen types serving detention in The Breakfast Club offered the truest glimpse of Hughes’ soul: was it the brain, the beauty, the jock, the rebel or the recluse? Hughes never fessed up to being the geek (in his definition: “someone who has the software, but not the hardware yet”), but we had our suspicions. As Molly Ringwald (who starred in three Hughes-scripted teen epics, culminating in 1986’s Pretty in Pink) noted, in his films it was the geek who “always got the last word. And he always got the girl.”

This theory is somewhat confounded, however, by stories of Hughes’ double life as creative director of an ad agency (aged just 27) and writer for National Lampoon magazine – some of his antics have definite shades of Ferris Bueller (Hughes’ only protagonist who’s actually popular at school). “Whenever I had to leave my office unattended,” he once recalled of his moonlighting days, “I stashed my magazine text in the wastebasket, covered it with my morning newspaper, dumped what was left in my coffee cup on it, and emptied my ashtray over the whole mess. At the end of the day I put it in a Leo Burnett Co. interoffice envelope, took it home, cleaned it off and transcribed it.”

Later, while working as an editor at National Lampoon (“for less than half of my Christmas bonus”), he developed scripts from short stories for the Lampoon films Class Reunion (1982, which he later disowned) and Vacation (1983). The success of another comedy he scripted, Mr. Mom (1983) – combined with his dislike of being, as he termed it, “the least important person” as scriptwriter – led him to convince Universal to let him direct Sixteen Candles.

Hughes will always be associated with the ‘Brat Pack’ whose careers he helped to launch, but initially financiers wanted him to cast better-known older faces who would bypass restrictive child acting laws. Hughes held firm, preferring to work with genuine teenagers who had no image of themselves to adhere to and could contribute to their characters in rehearsals. (“Make my hair stand up more,” demanded Anthony Michael Hall, Hughes’ regular geek.)

But what would happen when they grew up? Some Kind of Wonderful (1987) was Hughes’ last high-school film. In the care of others, the genre was to turn to satire (Hairspray and Clueless), nihilism (Kids) or both (Heathers). Hughes, meanwhile, transferred his attention to adults, though they were seldom completely adult adults. John Candy starred in two films for Hughes: as the slobbish kidult craving acceptance from Steve Martin’s straight businessman in Planes, Trains & Automobiles (1987); and as the unemployed, non-house-trained protagonist of Uncle Buck (1989), another character firmly in touch with his inner teen. Tellingly, it was the most grown-up of Hughes’ films as director – She’s Having a Baby (1988), about a man coming to terms with the responsibilities of parenthood and the boredom of suburban life – that proved his biggest flop.

In the 1990s, he turned to kiddie capers with the 1990 hit Home Alone, which he wrote and produced, and his last film as director, the box-office dud Curly Sue (1991). But these films still had that old Hughes theme at their core: a kid at the mercy of a dysfunctional family. In 1994 Hughes retired to his beloved Chicago suburbs and retreated behind the pseudonym Edmond Dantes (protagonist of Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo) for some of his remaining writing jobs (among them the dog comedy Beethoven). While generations of Converse-wearing adolescent misfits would prefer to forget that their patron saint ever stooped so low, one word of criticism against his teen films and you’ll invoke the famous warning from The Breakfast Club: “When you grow up, your heart dies.”

Isabel Stevens