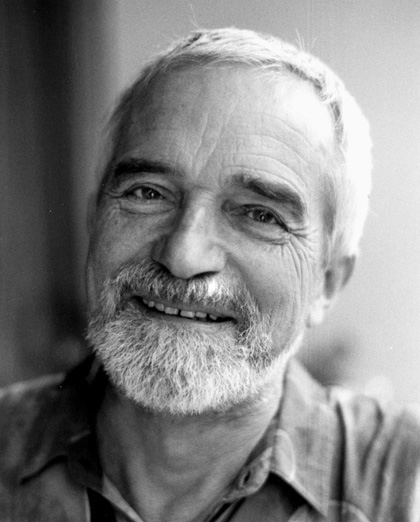

Robin Wood, critic

b. 23/2/1931; d. 18/12/2009

It is difficult to write in a dispassionate, academic manner about the death of a friend. In the case of Robin Wood, such an exercise would be a betrayal of everything he stood for. Robin’s constantly evolving body of work was always rooted in his own experience and animated by his belief that criticism that was not simultaneously personal and political (in the sense that the personal is political) must be doomed to irrelevance.

Wood, who died from leukaemia aged 78, was among the most important and influential film critics of his generation. Born in Richmond, Surrey in 1931, he read English at Cambridge, where he encountered F.R. Leavis, the self-styled keeper of English literature’s ‘Great Tradition’. Despite Leavis’ active hostility towards cinema, Robin’s work never lost touch with Leavisite ideals.

After Robin’s article on Psycho was published in Cahiers du cinéma, he began contributing regularly to the new magazine Movie in 1962. While working as a schoolteacher he went on to write Hitchcock’s Films (1965), the first book on Hitchcock to appear in English. This was followed by auteurist studies of Howard Hawks, Arthur Penn and Ingmar Bergman, as well as a series of articles engaging with the then fashionable schools of critical theory, which Robin struggled to reconcile with his own humanist approach. The turning point was his 1976 book Personal Views, in which he first wrote about coming out as gay. His article ‘Responsibilities of a Gay Film Critic’ appeared in Film Comment the following year, and set the tone for his work over the next three decades, during which he insisted that the only defensible reason for writing criticism was “to contribute, in however modest a way, to the possibility of social revolution, along lines suggested by radical feminism, Marxism and gay liberation.”

Such claims caused detractors to complain that he had become limited as a critic. But Robin – who could write with equal enthusiasm about Michael Haneke or My Best Friend’s Wedding – maintained that the opposite was true, pointing to his chapters of The American Nightmare to demonstrate how his political commitment enabled him to perceive value in films he would previously have dismissed as trash. In this landmark book, Robin developed his ideas about the horror genre, in particular the Freudian ‘return of the repressed’. The combination of Marx and Freud would be at the centre of his subsequent writing, much of which appeared in CineAction, a Canadian journal he co-founded in 1985 with his partner Richard Lippe and several of his students at Toronto’s York University.

It was in the pages of CineAction, as well as in the 1986 book Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan, that I first encountered Robin’s work; I felt I had discovered a writer who was telling me things I’d always thought, but never found the language to express. A series of letters to Robin, always answered in tones of warm friendship, led to his suggestion that I contribute an article on Michael Cimino’s The Sicilian to CineAction (my first published work) – and, eventually, to our meeting in London.

When I learned of Robin’s death, I recalled the following passage he wrote in Hitchcock’s Films Revisited (1989): “A Marxism crossed with feminism, incorporating a rethought humanism… might… eliminate, or at least greatly diminish, the fear of death [which] seems deeply connected to the sense of nonfulfillment – of energies dissipated in alienated labour, of potential cruelly wasted, of creativity frustrated. If the soul could blossom freely, it would fear death no more than the perfect rose fears the dropping of its petals.”

Brad Stevens