The White Stuff

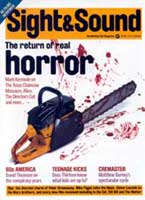

The Cremaster cycle is a visually stunning mix of biology, Houdini, Visconti and Vaseline. Mark Cousins salutes this remarkable art-film epic below.

It has taken nearly a decade to produce and runs for almost 400 minutes, but modern cinema's most discrepant series of films has now reached its conclusion. In 1994, when Matthew Barney began his Cremaster quintet, the director seemed hell-bent on creating a personal mythology as heterodox as Jean Cocteau's and on forcing his hero Joseph Beuys' fascination with the gloopy texture of material into an artform - cinema - that had never taken much notice of such things. Barney's mix of Vaseline, Harry Houdini, Celtic mythology, closed aesthetic systems and mutated genitals excited dissident cinephiles from the start, but it was too early to say whether his infractions of cinematic norms deserved to be taken seriously. As the cycle progressed, these doubts faded. The films' wordless tableaux became increasingly assured and by the fourth instalment the puzzle of Barney's references had extended into a rigorous maze of ideas.

Even allowing for the achievements of Cremaster 4 (1994), Cremaster 1 (1995), Cremaster 5 (1997) and 1999's Cremaster 2 (Barney has filmed and released the episodes out of sequence), few could have predicted that the latest and last instalment, Cremaster 3, would be so satisfying. Not only is it longer than the others combined, and the centrepiece of the cycle, but it introduces new layers to the already complex structure and is as arresting as such silent epics as Cabiria (1914) and Intolerance (1916).

Born in San Francisco in 1967, Barney took from his early success as an athlete an idea that became central to his work: that in order for a muscle to build, it must encounter resistance. Even his earliest sculptural and conceptual work pits creation against obstacles - Drawing Restraint II (1988), one of his first gallery projects, had Barney's attempts to draw on a wall constrained by apparatus attached to his arms and legs. And some 14 years later the storyline of Cremaster 3 would pit the architect of the Chrysler building in New York against a character called the Entered Apprentice (played by Barney) who destroys the building as it is constructed.

The equilibrium of a system of creation and destruction soon grew into a central metaphor. In Bolus (1991) - influenced by Beuys - Barney used frozen Vaseline to sculpt a dumb-bell-shaped object which he conceived as an oral and anal insertion to complete the circle of the digestive tract, a creative-destructive system not only in balance but also closed and self-contained. You could walk around it. This idea would shape the Cremaster cycle, which Barney has since referred to as a work of sculpture.

Somewhere along the way Barney saw Stanley Kubrick's The Shining and was impressed by how fully the empty hotel influenced the aesthetics of the completed work. Keen to use location in a related way, he translated the ideas of Bolus into an outline for a series of landscape artworks, and the Cremaster films were born. This outline took the form of a simple drawing of a bagpipe, entitled OTTOshaft (1992). The bag was a montage of two kilted Scotsmen sewn together at the knees and each of the five pipes - or drones - was named after a location: Bronco Stadium, a Columbia ice field, the Chrysler building, Ireland and Istanbul. Ireland became the Isle of Man and Istanbul became Budapest, but otherwise these would be the places used in each of the Cremaster films in their conceptual (1,2,3,4,5) order.

At this stage the films were conceived as records of staged events to be shown in galleries, but before embarking on the first Barney's ideas were augmented by what would soon become his most famous metaphor. Increasingly preoccupied with the process of sexual differentiation in human embryos, he applied the eastward journey mapped on the bagpipe drones to an allegory of the descent of the testicle. With this bizarre connection, the blueprint was complete. The muscle that raises and lowers the testicles - the cremaster - gave the series its name.

Cremaster 1, shot where Barney was born, represents the testicle at its least descended and is thus the most feminine of the films and the one most concerned with height. The scenario is remarkable and somewhat camp: two balloons float over Bronco Stadium, one containing a woman lying under a table picking red grapes through a hole in it and the other a woman doing the same with green grapes. Shot on analogue Betacam with tinny sound, the film is technically unpolished but wildly surreal, "slow like art" as Barney would later say. As befits the female stage of the embryonic process, Barney himself does not appear in it.

By the time he made Cremaster 2 on digital Beta, Barney had become a master film-maker. Again there are few social or historical co-ordinates, but inspired by Norman Mailer's book The Executioner's Song, about American murderer Gary Gilmore, whom Mailer argues might have been Harry Houdini's grandson, Barney created scenes as intense as the second half of Hitchcock's Vertigo. In a gas station before he shoots someone, Barney as Gilmore lolls in a Cronenbergian organic tract connecting two cars representing his own and his girlfriend's. He picks at the Vaseline linking the cars, uses it to create a messy sculpture, undresses to reveal a penis the size of a matchstick and almost no testicles - they are just beginning to descend - then leaves and commits the killing. Barney's editing is slower here, his camerawork more dreamlike, his soundtrack more brooding and the film more engaging and associative.

Cremaster 3 represents the mid point in the process of sexual differentiation, where male and female are in a Barney-esque tension, mirrored by the conflict between the Chrysler architect and the destroyer. The skyscraper rises and falls; Gilmore is represented by an emaciated female corpse that rises out of the earth at the base of the building; a legless woman played by Aimee Mullins cuts potatoes in a snug on high and embodies the Chrysler's unconscious life. The editing has slowed once more but the HDTV images are richer than those of the previous Beta films. The sense of indecision, of sexual and philosophical gridlock, is palpable and there's an overwhelming pathos: this is the moment before the scales will tip in favour of maleness and the balance will be lost forever.

To recreate the absurdity of this darker period of descent, Barney in Cremaster 4 dressed as a satyr and tap-danced his way through a pier in the Isle of Man, plunging down into the sea. Intercut with this are two TT vehicles racing around the island. From slits in the drivers' leather outfits, sticky gonads rise and fall. At the end of the film ribbons are attached from Barney's mutated genital sack to the vehicles, which rev in readiness to speed away.

For Cremaster 5, set in Budapest because that is where Houdini was born, Barney had Ursula Andress sing a heartbreaking operatic lament for a series of remembered embraces with her lover. Barney plays this character as well as Houdini, re-enacting the latter's famous dive into the freezing waters of the Danube. At the end, when Andress appears to fall asleep, saliva dribbles from her mouth into a swimming pool where water maidens tie ribbons to the penis of a Neptune-like figure, with their other end attached to doves.

Beuys, Cronenberg, Cocteau and Kubrick are among the artists Barney resembles - along with early David Lynch and the Visconti of Ludwig. On paper this sounds too rich a stew, but actually to watch the Cremaster films is to be seduced by the physical qualities of cinema. Barney's films have had ripped from their surfaces the rational layer of dialogue and worldliness we expect in movies. What is exposed is complex, but also, unexpectedly, moving.