Drive, He Said

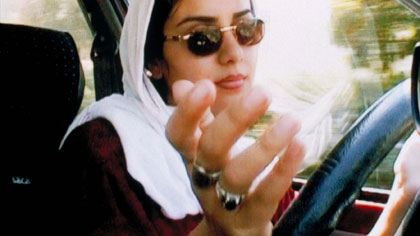

10 is a road movie set entirely in the front seat of a car. Who else but Abbas Kiarostami could have made it? Hitching a ride, Geoff Andrew rates it as among the director's richest works

When Abbas Kiarostami's 10 premiered at this year's Cannes, its reception was surprisingly muted given that the Iranian master's previous two features - A Taste of Cherry (1997) and The Wind Will Carry Us (1999) - each won the top prize when they were unveiled at Cannes and Venice respectively. 10's relatively low profile can probably be written off in part as the fate that awaits any 'small' work in an A-list festival, while the film certainly suffered from the proximity of its screenings and clash of its press conference with the first public appearance of the much hyped Miramax showreel for Scorsese's Gangs of New York. Against such competition, what hope was there for a modest movie rumoured to be a digitally shot documentary featuring women talking about their lives in Tehran?

Of those who bothered to see the film, a fair proportion - including some of Kiarostami's admirers - opined that it was simply more of the same (A Taste of Cherry, after all, was another so-called minimalist work largely made up of conversations in a car). But there were some, like myself, who felt they'd encountered something extraordinary; that this was probably the most audacious, innovative, relevant film in the entire festival. Certainly, since that first press screening in May, hardly a day has passed when I haven't puzzled over one of 10's many conundrums; in my head, at least, the film has grown in complexity, a development accelerated rather than halted by further viewings. Kiarostami, after all, is an artist who tries not to make films for consumption in the usual passive sense but wants to encourage us to think, question, decipher, to become active participants in the process he's set under way. All his films demand interpretation on several levels; he refutes the idea that his work should have a single fixed meaning. This is, then, an attempt not to impose a definitive reading on 10 but to suggest routes into the film which might offer a glimpse of its diverse riches.

10 consists of ten chapters or scenes, prefaced, respectively, by the numbers ten to one (in graphics reminiscent of the countdown on film leader); each takes place inside a car being driven around present-day Tehran. The digital camera or cameras, mounted on the car's bonnet (or very occasionally, it would seem, on the dashboard), are, with one brief but notable exception, trained either on the driver's seat or the passenger seat regardless of whether anyone's sitting there or who is speaking. There is no camera movement whatsoever.

In the first chapter (10) Amin, a boy probably in his very early teens, climbs into the car to be driven to the swimming pool by his mother (played by Mania Akbari); as they argue - mainly about her divorce from his father, Amin's dislike of his new stepfather and what he perceives as her selfish disregard for his feelings - we don't see the woman but only hear her increasingly strident voice trying to make itself heard over Amin's tantrums. Only after about 15 minutes, after he storms from the car, are we finally shown Akbari, drained by the quarrel and testily trying to park.

The next chapter (9) opens on a prolonged shot of another woman sitting in the passenger seat, evidently alone and unselfconsciously picking at spots on her face and fanning herself beneath her veil; finally a cut announces the arrival of the driver, who is again Amin's mother. The passenger is Akbari's character's sister, and as Akbari drives her home they discuss their husbands' birthdays, Amin's moodiness with their own mother and whether Akbari should allow him to live full time with her ex-husband. In the next segment (8) Akbari gives a lift to an old woman who visits the local mausoleum thrice daily and (unsuccessfully) tries to persuade her driver to take up prayer; in chapter 7, shot at night, Akbari asks her prostitute passenger about her life, work and attitudes to love and sex. In both these scenes the camera remains fixed on the driver's seat: we see the old woman only when she enters and leaves the car and the prostitute (in the aforementioned exceptional camera angle, looking forwards through the windscreen) only as she walks off into the street where she is approached within seconds by two kerbcrawlers.

By now most viewers will probably feel that the disjointed scenes are starting to take on a vague narrative shape. In chapter 6 Akbari collects a friend from the mausoleum and they discuss why each has recently taken up prayer: for Akbari it alleviates occasional feelings of guilt, while her passenger hopes that prayer might help to diminish her boyfriend's hesitancy over marriage. In episode 5 Akbari has a slightly less heated meeting with Amin, who screams that she's taking the wrong route to his grandmother's house and lets drop in passing that his father (with whom he's now living) watches "sexy" programmes on television late at night. Akbari is then seen collecting another friend to go to a restaurant; en route the woman sobs that she's distraught at her boyfriend having left her, while Akbari insists she should love herself more and not let her happiness depend on one man. In chapter 3 Akbari jokes with Amin about getting his father to remarry someone with a daughter suitable for himself, and even copes amiably with the boy's insistence that she prioritised herself and her work over becoming a good wife and mother. In chapter 2 Akbari again collects the friend seen in chapter 6, who is now upset by her boyfriend's decision not to marry her. When the woman's veil slips to reveal she has cropped her hair Akbari encourages her to remove it altogether, and compliments her on her courage, beauty and sensible attitude to the break-up. Finally, in a very brief chapter 1, Akbari collects Amin from his father and the boy at once demands to be taken to his grandma's. His mother simply replies "All right" before the image fades to black and the credits roll.

Given what may appear to be a randomly structured narrative and the absolute plausibility of everything we see and hear, it would be easy to assume that 10 is a fly-on-the-windscreen documentary. But Kiarostami is a director who repeatedly returns to that treacherous but very fertile no-man's land between fiction and non-fiction, and 10 is merely the latest and arguably most sophisticated in a series of forays into phenomenological and narrative ambiguity that have included Close-Up (1994), And Life Goes On... (1992) and Through the Olive Trees (1989). Here the driver and the passengers in the car are 'acting'; they were mostly chosen after auditions at which Kiarostami asked ordinary people to tell him about their lives. Having selected his cast, he entered into long discussions with them and decided what he wanted their characters to talk about during the different journeys: sometimes that might be left quite open, sometimes he was very specific. (It's impossible to tell which were the most precisely planned episodes, though the contribution of the prostitute character was carefully devised as probably was that of Amin.) Unlike in A Taste of Cherry - where contrary to appearances the actors were addressing Kiarostami and his camera and were never actually in the car together - here the director was usually absent when the film was being shot. The finished film was thus the result of extensive preparation and discussion, and then of extensive editing (its 94 minutes were assembled from some 23 hours of footage).

Why such methods? Partly because, as Laura Mulvey has noted, Kiarostami has always concerned himself with exploring "the narrow line between illusion and reality that is the defining characteristic of cinema." But one can't help feeling there are other things going on in 10, specifically linked to Kiarostami's conversion to the digital camera. The 'realism' on view here is unimaginable without the new technology: before digital any camera would have been too obtrusive, distracting the actors and making them self-conscious. Kiarostami has spoken of his desire to make direction itself disappear - presumably so his 'actors' can become wholly involved in their characters (which are often developed with reference to their own experiences, ideas and emotions) and so there's nothing to distract the viewer from what he considers most important, namely the individuals on (and just off) screen. This simplicity and directness make 10 both accessible and affecting: we are never waylaid by a virtuoso camera movement, a heart-tugging underlay of music, a flourish in the editing. What you see and hear is what you get... except that, this being Kiarostami, it sometimes isn't.

On one level the film deals with what can and can't be depicted or discussed within the strict codes of cinematic conduct laid down by Iran's post-revolutionary government. 10, after all, is primarily 'about' the lives and status of women in modern Tehran. Though Kiarostami said at his Cannes press conference that no objections were raised to the film when he submitted it for approval by the authorities, it's often brazenly iconoclastic. When Amin complains that his mother wrongly accused his father of being a drug addict, she replies that "the rotten laws of this society give no rights to women" and that to invent stories about addiction or beatings is often the only option for women suing for divorce. Her conversation with the prostitute is disarmingly frank: the girl is clearly unrepentant about her work, admits she enjoys sex and argues that what she does is no different from what wives do - except that "You're an idiot, I'm smart." (Kiarostami included the single brief exterior shot of a woman streetwalking to prove how quickly one of Tehran's many kerbcrawlers would pull over.) Akbari then tells her sobbing friend that men are fickle and two-a-penny, bemoans that many are interested only in "a big ass, or big tits", and decries her son and ex-husband for wanting an obedient woman who would cook and clean rather than an independent, intelligent and creative professional. Most subversive of all, however, is the unexpected, epiphanic and deeply moving moment when her other friend lets her scarf drop to reveal a close-cropped head. The Islamist code forbids women in Iranian films to be shown without a veil, and this scene not only breaks that ruling but does so in a context that acknowledges female sexual desire, gives voice to criticisms of unjust divorce laws, and implies that many men (and the deeply macho boy who serves as their representative) are hypocritical, fickle and antiquated chauvinists.

At the same time, however, Kiarostami is playful, even sly in his response to what can and can't be shown. That we never see the prostitute in the passenger seat implies she's a real streetwalker, when in fact the prostitutes auditioned were reluctant to use the vulgar language the director wanted for the scene so he was forced to find someone to play the part. Likewise he also barely shows us the devout old woman - out of respect, or perhaps to hint that these two characters, who embody traditionally polarised notions of sacred and profane femininity, are more interesting for what they have in common than for what divides them.

Both in terms of individual characterisation and through the structure he gives the film, Kiarostami avoids stereotyping and oversimplification. In the first episode, for instance, Akbari sounds strident and hectoring, but as the film proceeds we're forced to reassess not only that impression but many subsequent ones. While her smiling rejection of the old woman's suggestion that she should pray seems exactly what one would expect of this relatively well-off, free-thinking divorcee, we later learn she's acted on that advice; she may be strong, but she seeks peace of mind. That the encounter with the prostitute is shot at night might imply the character is being singled out as morally different, yet she is never judged and makes a strong case for the practical wisdom of her career choice. Then the scene with the jilted woman (chapter 4) also takes place at night, creating a visual link with the prostitute, who, we remember, confessed in passing that she herself had once been let down by a man. Moreover, the argument Akbari uses to comfort her weeping friend echoes many of the sentiments voiced by the prostitute in the earlier episode. Chapter 4 thus functions in various ways: as a portrait of a recently jilted woman which, through its subtle allusions to the previous encounter with the prostitute, reflects both back to the streetwalker's past and forwards to what might befall Akbari's friend if she can't overcome her dependence on men; as another step in Akbari's own growing self-confidence and self-awareness; as another tale of male selfishness and unreliability; and as a scene which explores different reactions to being abandoned, through Akbari's friend, the prostitute, and the passenger in chapters 6 and 2 whose unveiling stands as 10's dramatic, moral and emotional climax.

In so far as Kiarostami bothers to create a conventional climax, that is. Unconcerned with proffering the usual conflicts and resolutions, he ends the film on a seemingly inconclusive note, with Akbari merely agreeing to her son's insensitive demand that he be driven straight to his grandmother's house. It's less a closure than an admission that life goes on, for the audience as well as for the characters; we've been presented not with a self-contained story but with fragments from several 'stories' that throw light on each other, and we're invited to make of them what we will. The overwhelming impression left by 10, in fact, is of an artist trying to create a new kind of cinema - pace those in Cannes who carped about Kiarostami treading water.

That said, the complainants could have a point. 10's first 15 minutes find the camera trained exclusively on a young boy - and the child protagonist, the car and the journey are all motifs familiar from the director's earlier films. But Amin, for all his love of cartoons and other boyish traits, is most memorably an embodiment of adult masculine oppression in embryonic form. And the vehicle here is mainly a means of throwing Akbari into close proximity with a variety of people and of limiting conversations to the duration of short city journeys - journeys which are far less visually spectacular than the mountainscapes of many of the earlier films. The focus is on faces throughout, and the use of just two camera angles essentially isolates the characters in the frame: we may hear their partners in conversation, but the driver and her passengers don't touch - except, first, when Akbari feels Amin's feverish forehead, only to have her love rejected when he fails even to acknowledge her concern; and second, when Akbari's friend removes her veil and we see the driver's hand enter the frame to wipe away her tears. It's as if Kiarostami were saying that rules - social or self-imposed, cinematic or ideological - can and should be broken when human needs and happiness are at stake.

Is this, then, the same old Kiarostami? No, in that he's covering new territory (none of his previous films centred on women) and pushing his stylistic reserve to greater extremes; yes, in that familiar themes, formal tropes (repetition, simile, reversal, inversion, etc.), the quizzical take on reality and the unsentimental, profound humanism remain very much in evidence. With 10 the contradictions are more intriguing, the paradoxes go deeper. Even more than before, there's simplicity but also sophistication; complexity but also clarity; diversity yet coherence; and fictions, secrets and lies are an essential part of the strategy for getting closer to truth. Then there's the remarkable decision to eliminate 'direction' itself from the equation, not only by working without a script but by absenting himself from the 'set' and simply letting things happen; only at the editing stage does he exert control over what's already been recorded.

In a sense this is a logical development from earlier work where events and characters offscreen were as important as those onscreen. Yet just like the boy the director is looking for in And Life Goes On... or the ailing old lady in The Wind Will Carry Us, Kiarostami in his absence remains a haunting presence throughout. That's not merely because Akbari, with her habit of questioning her passengers about their lives, might be seen as yet another surrogate director in Kiarostami's work; it's also because we sense that no one else could have made 10, and no one else would have tried.

Krzysztof Kiezlowski once told me of his affection for what he regarded as his most personal film, Three Colours Red: "It's a bit like one of those car commercials you see on television: it seems so small - there's no action - and yet it's so large inside. There are so many layers there you can find if you want to." The same, perhaps, might be said of 10, which constitutes another crucial advance in a career that has merged humanism, rationalism, mysticism, modernism, postmodernism, socio-political comment, realism and poetry to unique effect. In contrast with so many films being made today, it has nothing to do with flashy technique, fashion, stars, big budgets, special effects, self-aggrandisement or marketing opportunities, and everything to do with using cinema as a tool for the cool, sympathetic contemplation - and celebration - of the uncertainties of everyday life. It may just be that Kiarostami's quiet minimalism, more than anything else now on our screens, points to the most richly rewarding route cinema might take on its journey into the future.