East Of Eden

The nostalgia for Communist GDR days in the political satire Good bye, Lenin! charms all us running dogs, says Dina Iordanova.

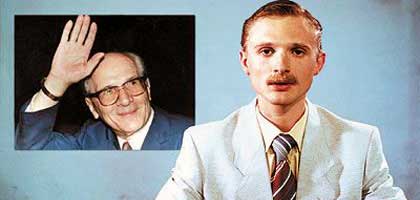

The scene is East Berlin, October 1989, on the eve of the German Democratic Republic's fortieth anniversary. With barely a month to go before the fall of the Wall, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev is in town, putting on a show of everlasting fraternity with GDR premier Erich Honecker. Twenty-year-old Alex (Daniel Brühl) shares an apartment with his mother and sister; his father defected to the West ten years earlier. When the mother (Katrin Sass, a veteran of East Germany's DEFA studio), a teacher and devoted party functionary, sees her son taking part in an anti-government demonstration, she is so shocked she has a heart attack.

While the mother remains in hospital in a coma political events gather speed. By the time she comes back to her senses eight months have passed, the Berlin Wall has fallen and the GDR is no more. Her daughter Ariane (Maria Simon) has quit her studies to work at Burger King. Alex has become a salesman with a satellite-dish company, bringing new means of access to the airwaves over East Berlin.

Though their mother looks likely to recover, her children are warned that any excitement could prove fatal. Alex knows news of the end of Communism will come as a profound shock, so he persuades the doctors to let him look after her at home. Here he establishes an increasingly complex operation to make time stand still: within their 79-square-metre apartment, the GDR lives on.

Made for DM8 million (about $4.7 million) and having earned more than $40 million in revenues to date, Wolfgang Becker's Good bye, Lenin! has done spectacularly well by the standards of European cinema. Within three months of its premiere at the Berlin film festival in February it had been seen by more than 5 million Germans, a total made possible by good word-of-mouth backed by a Hollywood-style saturation release of more than 500 prints (co-ordinated by Warner Bros.' European arm). Distributor Bavaria Film says Good bye, Lenin! has been sold into more than 40 territories. With its clever knitting together of comedy and politics, its closest precedent is perhaps Jan Sverák's Oscar-winning hit Kolja (1996), in which the bond between an ageing Czech man and a Russian boy triumphs over the protagonist's anti-Russian prejudice.

Similarly, in Good bye, Lenin! a caring young man from East Berlin puts his anti-GDR sentiments on hold for the sake of his mother's health. But a host of unexpected obstacles increasingly take up Alex's time and resources. His mother's favourite Spreewald gherkins disappear from the grocery store to be replaced by Dutch imports as do other familiar products, with the result that Alex spends a considerable amount of energy retrieving old jars and repacking foodstuffs to keep up appearances. Sometimes he overdoes the act, especially when he tries clumsily to involve other people, asking visitors and friends to lie about their backgrounds, bribing his mother's former pupils to perform pioneer songs for her and dragging an alcoholic former party secretary out to give a speech on her birthday.

For a while his mother remains blissfully unsuspecting, though she can't help but make some puzzling discoveries. Wandering out of the apartment, she notices some westerners moving into the building; she sees billboards advertising western brands and Lenin's giant sculpted torso being taken away by helicopter. Every time she comes near to finding out what has happened, though, Alex saves the day with a plausible explanation. His lies become ever more phantasmagorical: the presence of the westerners, for instance, is excused as a consequence of Comrade Honecker's new initiative to grant asylum to those disillusioned with capitalism. Alex and his friend Denis produce television reports that proficiently combine documentary footage with re-enacted episodes and (very funny) readjusted commentary, which they play on a television monitor from a VCR in the adjacent room.

As J. Hoberman has noted, the only 'co-production' between East and West Germany before 1995 was the Berlin Wall. A visit to East Berlin before 1989 would always involve listening to legends about resourceful individuals who had breached it: by digging a tunnel underneath, by swimming underwater across the Spree, by using ropes stretched between the windows of buildings on either side. Many films featuring the effects of the Wall Wim Wenders' Wings of Desire (1987) and Faraway, So Close! (1993), Margarethe von Trotta's The Promise (1994), Roland Suso Richter's The Tunnel (2001), even John Cameron Mitchell's Hedwig and the Angry Inch (2001) are peopled by protagonists suffering from what was commonly known as Mauerkrankheit or Wall-sickness.

Then came the films set in the new Berlin, such as Tom Tykwer's Run Lola Run (1998) or Wolfgang Becker's local hit, co-written by Tykwer, Life Is All You Get (1997). East Berlin had changed. The once run-down Prenzlauer Berg (location of DEFA's 1979 cult classic Solo Sunny) now became the centre of cool, with GDR nostalgia spawning renovated retro premises where as seen in Good bye, Lenin! young girls wear Russian nurse uniforms as a fashion statement. But Good bye, Lenin! has a unique place in this Berlin series because of the film's radical revision of the Wall's narrative standing: in most other Berlin films the Wall is the problem; here it is its absence that causes complications.

Forty-nine-year-old director and co-writer Wolfgang Becker was born and raised in the West and claims this distance allows him to see things more clearly. Extensive research into the "East German state of mind" led him to conclude that, contrary to popular belief, not everyone hated life under state socialism. The well-publicised images of crowds cheering the Berlin Wall's demolition that marked the Cold War's end left those who needed the Wall's protection out of the picture. When Communism collapsed, many people across the Eastern Bloc were ill prepared for the knock-on effects on work and domestic routines. In place of the old institutional evils a host of new ones arrived. Those who had nurtured an idealised image of western prosperity were startled by the increasing economic disparities within their once egalitarian universes. Confronted with a collapse of ideology, many were plunged into an identity crisis.

From a storytelling point of view, though, this was an extremely rich time. Film-makers from across Eastern Europe witnessed events that provided harrowing dramatic material. Time and again they dealt with gloom and despair, presenting frail characters battered by the mighty sweep of historical change. Films such as Ibolya Fekete's Chico (Hungary, 2001) featured individuals confounded by the volatility of a crumbling political system. The unique attraction of Good bye, Lenin! in this context is that here the protagonists try to customise the story for themselves.

The East Germans' precarious position is well illustrated by Alex's losing out when he tries to change the former East German currency into Deutsche Marks. The siblings manage to recover their mother's hidden life savings but only when it's too late to make the exchange. So Alex can only throw his inheritance from the rooftop in a symbolic gesture of parting with the past. He knows that even if it had been exchanged, it wouldn't have given him much leverage in the new economy.

The panorama of economic disparity widens when Alex's father comes on the scene. Alex always thought his father had abandoned the family, but now he learns that his mother chose to stay in the GDR when his father left. His father has since done quite well in West Berlin; his stately suburban villa presents a sharp contrast to the mother's modest flat. It's not that Alex cares very deeply, it's more that he can't ignore the differences between the two environments. The film's key message the voicing of suppressed discontent over the East Germans' newly acquired runner-up status is delivered by Alex in a seemingly rambling voiceover remark that brings together exchange rates and football scores: "The exchange rate was two to one, and Germany won, 1:0."

Alex is young, whereas most post-Wall films are filled with grumbling, disenfranchised pensioners. These are the real losers: full citizens before reunification but now marginalised and mocked, they are well aware that the only thing society expects of them is that they fade quietly away. One of Good bye, Lenin!'s most resonant subplots features a chance encounter between Alex and his one-time idol Sigmund Jähn, East Germany's only astronaut, now reduced to driving a taxi. Alex is quick to figure that he can use Jähn for his media fabrications and soon has him deliver a videotaped speech in which he poses as the GDR's newly appointed president. Even if it's only in a fake television report, here at last one of the losers takes control of history.

As the discrepancy between real life and Alex's contrivances grows, he realises he is adjusting the truth not only for his mother's sake but for himself as well: "The GDR I created for her increasingly became the one I might have wished for," he admits. He would much prefer it if refugees from the West were indeed flooding into East Germany and if it were the GDR which was guiding the country towards reunification. Had things happened Alex's way, East Germans wouldn't be passive bystanders but purposeful interventionists.

The reality, however, is that Alex's fellow GDR citizens eagerly allowed themselves to be taken over. The objects of their material culture were rapidly reduced to the status of useless props and replaced by western brands (represented here by plugs for Coca-Cola and Burger King); nostalgia for this lost popular culture manifests itself in a renewed interest in old clothes, objects and buildings, with several exhibitions focusing on the paraphernalia of everyday life under Communism, such as the Trabant car.

A similar nostalgic urge has been present in Eastern European cinema. A number of box-office hits paint an idyllic picture of life under Communism, functioning as a corrective to western propaganda. Emir Kusturica's Do You Remember Dolly Bell? (1981), set in the 1960s, catered to audiences' need to affirm that coming of age or falling in love were equally thrilling under any political system. In post-Communist Hungary the stylish musical Dollybirds (Péter Timár, 1997) showed local apparatchicks as singing and dancing pub patrons; in Germany Leander Haussmann's coming-of-age film Sun Alley (1999) featured rock-loving teenagers dancing in the shadow of the Wall.

This revisionism is particularly apparent in screen portrayals of Russians. The former coloniser became a permitted subject only recently, but instead of articulating long-standing resentments film-makers have tended to humanise Homo Sovieticus by depicting him as a vulnerable human being. Once dreaded in Germany, the Russians have been transformed in film into perplexed army deserters (Dusan Makavejev's Gorilla Bathes at Noon, 1993; Zoran Salomun's Weltmeister, 1994; Andreas Kleinert's Neben der Zeit, 1996). Then screenwriters turned to Russian women, showing them as trapped prostitutes, mail-order brides or visiting nurses, as is the case with Alex's love interest Lara (Chulpan Khamatova). Why absolve the Russians? Because it's one of the few subjects about which one can be generous.

Earlier films about the Communist period may have over-stressed the bleakness, but many critics feel the 'Ostalgie' films are going to the other extreme. How do memory and history relate? Good bye, Lenin!'s sobering message that parallel histories are created for the sake of reconciling memory - is somewhat obscured by the film's insistent preoccupation with family. "It's not a film about the fall of the Wall," says Katrin Sass. "It's about a mother and a son, a family. It's a story the audience should be able to relate to with or without the historical background." And Becker himself insists that the 'universal' family essence of the story can be "totally separated from this specific past."

But can it? Whatever Becker's declared intention, Good bye, Lenin! is not an existential 'Mother and Son' story (as in Aleksandr Sokurov's film by that title). Good bye, Lenin! is both a political film and a film about memory, and as such it can't be divorced from its "specific past". Whether its makers are aware of it or not, it's a film about our personal relationship with history, about what people choose to recall and the way revisionist histories emerge when individuals are denied agency and participation. Good bye, Lenin! tells of history not as it is, but as we, the losers, would like it to be.