Mother Courage

Panic Room situates Jodie Foster in a yuppie-in-peril tale resounding with echoes of her past career, from the strained fear on her face to the screen daughter who reminds us of Jodie's child roles. She's an ageless icon of female cool, says Linda Ruth Williams

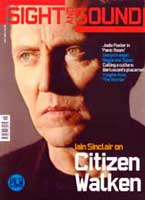

Jodie Foster, consummate child star turned accomplished Oscar-winning actress, will be 40 this year. Since 1966 she has notched up more screen performances than many a veteran twice her age by virtue of starting her career when she was three as the Coppertone suntan-lotion baby. The fact that she's been around for such a long time should not detract from the almost Wellesian proportions of her youthful achievements: she won her two Best Actress awards before she was 30, for Sarah Tobias in The Accused (1988) and Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs (1991). Critics endlessly comment on how remarkable it is not only that a successful child star, shaped and managed by a single-parent mother in a fatherless household, metamorphosed into the most respected adult actress of her generation, but that such a level-headed woman emerged from the exposure of early controversy. Writers eulogise Foster's professionalism, noting the veneer of ordinariness that encases her extraordinary success, belying the suspicion that she ought to be as maladjusted as a Royal Tenenbaum, as freaky and freaked-out as child-star casualties from Drew Barrymore to Michael Jackson. Foster admits an autobiographical connection with the genius child of a single mother at the heart of her 1991 directorial debut Little Man Tate. Yet she dismisses any lingering impact from the limelight that dogged her past: "I don't think somehow that I am walking wounded from my childhood in the film industry." Nevertheless, she had a central role in a presidential-assassination attempt (John Hinckley gunned down Ronald Reagan and three of his aides in 1981 in order to impress Foster having seen her in Taxi Driver) and has braved scandals such as an attempted 'outing' and persistent gossip surrounding the paternity of her son. More Hepburn than Garbo, it's reserve rather than reclusiveness that seems to characterise her private persona.

But if Foster has insisted on the "boring" quality of her personal life, she has embraced a cluster of contradictions in her work. Her child roles in dozens of commercials and in such television series as The Partridge Family and Kung Fu traded on her Californian golden-girl looks: blue eyes, blonde hair that chops and changes from curtain-of-corn to sharp bob, skinny bronzed limbs. But as a graduate of Yale University and, before that, of the elite bilingual Lycée Français de Los Angeles (which enabled her to translate for Scorsese at Cannes when promoting Taxi Driver), Foster didn't shape up into bimbo fodder. Even the sexualised roles that marked her work as a young adult (from Foxes, 1979, to Catchfire, 1991) present femininity as riven by dark desires rather than erotic availability. Indeed, her actorly filmography is a surprisingly mixed bag: child performances from the 1970s marked by an unsettling maturity; feisty 'women on the edge' in the 1980s; partners to unlikely leading men in the 1990s (the luminous romantic match for Richard Gere in Sommersby, 1993; a flirtatious poker-playing foil to Mel Gibson in Maverick, 1994; a coquettish whore in Woody Allen's Shadows and Fog, 1991); and post-Clarice Starling leading ladies who single-handedly carry major mainstream productions (Contact, 1997; Anna and the King, 1999; and now Panic Room). Foster also has two promising directorial ventures under her belt: Little Man Tate and Home for the Holidays (1995), quirky comedies that extend her image as a 'serious' thespian. And she helms her own production company, Egg Pictures.

Violence and victory

Foster has chosen to mark her fortieth year with David Fincher's Panic Room, a routine thriller that unpacks a number of genre staples. Here she portrays the film's sole repository of responsible adulthood, a sensible grown-up who under pressure metamorphoses into a risk-taking action woman. Foster's character Meg Altman and her screen daughter Sarah (Kristen Stewart) hole themselves up in their grand Manhattan brownstone's 'Panic Room' - an impregnable hideaway at the core of the house designed as a sanctuary against intruders - when three comic-book villains arrive in search of a buried fortune. This is essentially a surveillance suspense story, paying homage to Hitchcock (of course) in its obsession with the equivocal power of technologised looking. After Rear Window (1954) and lesser explorations of urban voyeurism such as Phillip Noyce's erotic thriller Sliver (1993), Panic Room presents us with yet another cinematic realisation of the Benthamite panopticon, the room being the hub of a spider's web of monitors and cameras that catch the robbers' every move. Trapped but (virtually) untouchable, the women see all without being seen themselves. One repeated two-shot features mother and daughter peering incredulously into the monitor in which Fincher's camera is positioned, so that as they survey the criminals they look directly to camera, and at us.

Though Panic Room is in part a woman-in-peril movie, scenes such as Meg's involuntary witnessing, via the monitors, of her husband's savage beating constitute a perverse wish-fulfilment for the abandoned wife - she responds with a primal scream of agonised contradiction. Another trademark Foster expression is that of strained fear, which becomes most resonant when her character is on the offensive. Here she reprises something of the 'Final Girl' aspect of Clarice Starling, and the dissolving shot on her stunned, blood-splattered face close to the conclusion is emblematic of an ambivalent relationship with violence and victory.

If Panic Room owes much to the yuppie-in-peril films that surfaced in the early 1990s (Pacific Heights, Unlawful Entry), it also resembles the Home Alone movies, suggesting that husband- and father-less women are as vulnerable as the diminutive Macaulay Culkin. Meg proves at least as resourceful as Culkin's character, rising to the challenge of the invasion with the rage of a mother whose brood is threatened, clad in the nifty black wardrobe of a cat burglar. The extended sequence in which she nips around the darkened house, measuring up to her assailants, is reminiscent of The Silence of the Lambs' final chase, when the roles of pursuer and pursued become increasingly blurred. The villains may be formulaically defined by comic idiocy; her ex may be incapacitated by injury; her daughter may be disempowered by adolescence and illness; but Meg does what has to be done. She hits all the marks of good parenting in times of crisis: completely focused on the well-being of her daughter, reassuringly inventive, steadfastly consistent. Feats of repression and suppression flicker across that eloquently furrowed forehead: Foster does tense worry like no other actor. I don't think she smiles in the course of the entire film, unless it's the odd glimmer of relief when the rollercoaster plot takes her up. During the estate agent's tour we learn Meg has claustrophobia ("Ever read any Poe?" is her first response to the Panic Room), but this is briskly put aside once she realises that only her level-headedness will ensure her daughter's survival. We just glimpse the deep waters raging beneath the still surface when she tucks Sarah in with the bedtime endearment, "It's disgusting how much I love you."

Single mothers and orphans

Meg's determined control is typical Foster. But much as Foster represents the consummate grown-up woman of contemporary cinema, there's also something ageless about her, something unsettled and unsettling in her ability simultaneously to embody naive youth and reflective maturity through explorations of adult childishness and the proximity to childhood mothering brings. An unease about the division of child from adult, adult from child, has characterised her most significant roles. Even the capable Meg confesses that post-divorce she is "going back to school - Columbia", so sketching a backstory of female development frozen by too-early motherhood. Foster the celebrity single mother, herself the daughter of a single mother, has given us three remarkable lone-parent portraits in the last ten years: action woman Meg was preceded by Dede Tate, mother of the child protégé in Little Man Tate, and Anna Leonowens in Anna and the King, widowed with a small son and coping on her wits in 19th-century Siam. In between she also directed Holly Hunter as a single mother thrust back into the bosom of her dysfunctional family in Home for the Holidays. Add to these the bereaved daughters mourning the death of a lone-parent father (Ellie Arroway in Contact; Clarice Starling) or lone mother (the eponymous Nell, 1994) and you have a slew of women struggling to cope with the repercussions of an incomplete family and not always positioning themselves on the right side of the child-parent divide. Only Nell manifests her response through emotional externalisation and a weird way with language; single mothers and orphans alike, Foster's characters are incompletely repressed, struggling for a linguistic precision with which to paper over the cracks.

Foster has been likened to America's grandes dames. One writer called her "the Eleanor Roosevelt of Nineties Hollywood" and Bette Davis herself remarked, "She's damn good. She's a young Bette Davis." But her position vis-à-vis class is far from straightforward: Hollywood's 'classiest' actress, an intellectual patrician figure, is driven by liberal sensibilities and a penchant for playing working-class women (even Clarice is "not more than one generation away from poor white trash"). Dede Tate and Sarah Tobias in particular recall 19th-century images of working-class women infantilised by class and gender. And though their struggles are presented mainly as the result of gender issues - Sarah's need to validate her experience of rape; Dede's mothering dilemmas - Foster's feminist choices are often underpinned by a class agenda. In The Accused, Little Man Tate and Nell her underclass figures are pitted against ambitious, professional, middle-class women who offer a different style of mothering (Kelly McGillis' lawyer, Dianne Wiest's educationalist, Natasha Richardson's psychologist respectively). From such a fiercely articulate person (she confessed in 1996 that as a child she "wanted to be a professional talker" when she grew up), Foster's on-screen displays of mumbled and humble inarticulacy are mesmerising: compare the bare bones of the screenplays with the fleshed-out performances and you appreciate the full force of what she achieves with her tongue-tied characters.

Foster has said that her preparation for her roles consists essentially of critical interpretation, for which her literature degree trained her well. Interviewed by Melvyn Bragg for The South Bank Show in 1995, she noted, "The real skill, for me anyway, is the literary criticism that comes before the acting." Her characterisations are not precious or Method-driven, but they are forensic. Foster starts with private textual analysis to produce three-dimensional emotional precision. Though she chides herself that "I didn't end up having the personality to be a writer, to be a novelist," the performances that result from her readings are themselves a kind of text, undertaken to "influence other people's lives and experiences in the same way that psychologists would or a novelist would."

Fallen angels

If Foster's female characters are grown-up children, this may be because they're haunted by the girl actor whose sassy hard work paved her career in the 1970s. As a child and teenager Foster portrayed youth at its most disturbingly adult, notably as Iris, the 12-year-old prostitute of Taxi Driver, and Tallulah, the pocket-sized speakeasy broad in Alan Parker's bizarre gangster movie for kids Bugsy Malone. These 1976 roles were followed by a child murderer in The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane (1976) and preceded by a streetwise child drunk in Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (1974). For each fallen angel, though, there's a feisty apple-pie Disney favourite, often hoodlums-with-a-heart (Foster was popular with the studio from her first film appearance in 1972 at the age of ten in Napoleon and Samantha with Michael Douglas, through One Little Indian and Tom Sawyer in 1973 to Freaky Friday and Candleshoe, both 1977). A common set piece for the serious Hollywood actor in the 1990s was to reveal the child persona buried within the adult frame, for instance Tom Hanks' grown-up-before-his-time in Big or Robin Williams' man-child in almost everything. Before these came Foster's mother-daughter in Freaky Friday (a body-swap tale that prefigures such films as Face/Off) where mother and daughter change bodies one Friday the 13th, requiring the 15-year-old Foster to play both adolescent daughterhood and 35-year-old motherhood. Directing her in a film which marks the end of this period (Foxes), Adrian Lyne said, "You felt that she was more mature than her mother."

Post-Yale and pre-The Silence of the Lambs, Foster repeatedly explored the unlucky choices women make, loving what's bad for them and betraying what's good for them, or - as in The Accused - straying into the ambivalences of desire while still claiming the rights of full agency. Foster did well to campaign so hard for the Starling role, which obliterated single-handedly the pursued-victim image of her 1980s parts. As a strong woman whose self- and image-control are legendary, surprisingly often the contradictions on Foster's screen face are driven by a masochistic aesthetic. She may announce herself to be a feminist humanist (as she did to a cheering audience at Yale in 1998), but her heroines are seldom paeans to liberated politics or political correctness (thank goodness). Indeed, The Accused is prefigured by a series of rape scenarios (and followed by its consequence: Nell is the product of a rape). In Carny (1980) Foster plays an adolescent who runs away to join the carnival and is assaulted by a gang of men at a strip show before being tied up and forced to the point of near-rape. In Five Corners (1987) she is terrorised by John Turturro as a rapist released from prison after attempting to rape her in the past. In Hotel New Hampshire (1984) her open-to-anything wild child Franny is the victim in an unsettlingly comic gang-rape scene after which she writes love letters to the lead rapist. This ill-judged comedy of errors also features a wacky extended family that includes gay taxidermist brother Freddie, dwarf sister Lily and doting brother John (Rob Lowe), with whom Franny initiates a fast-motion eight-hour bout of incestuous sex (after coupling with Matthew Modine's revolutionary pornographer and Nastassja Kinski's lesbian in a bear suit).

But at least the incest is consensual: in other roles Foster picks open the sticky issue of where complicity ends and force begins, prefiguring The Accused's talking-point analysis of the question. Catchfire, a noirish romance which director Dennis Hopper donated to the ranks of Alan Smithee films, features Foster as a conceptual artist who stumbles on a Mob hit and goes on the run. One of her artwork signs, reading "Protect me from what I want", might serve as a motto for Foster's 1980s women. Here she ends up wanting her murderous pursuer, who becomes sexually obsessed with his quarry when he sees photographs of her in kinky underwear. Foster's character reciprocates after being handcuffed and told, "Your life is mine, and you belong to me."

In the 1990s Foster shifted gear, incarnating a series of delicately drawn, repressed women of whom Meg Altman is the latest. Hollywood's long flirtation with psychoanalysis notwithstanding, Foster is now perhaps unique in being smart, or well read, enough an actress to understand the fascination of neurosis, the wound around which most interesting characterisations revolve. Nor does she fear the psycho-social stigma attached to the neurotic woman. Many of her later characters - Clarice, Anna, Ellie in Contact - bear their mental fissures like badges of accomplished human-ness. Foster has taken the impotence out of feminine neurosis. But uneasily repressed as these women may be, they are also effective agents, firmly grasping the symbolic order as they strive to wield public power. If this was driven only by a desire to produce positive female images it would be unspeakably dull, but Foster cautiously tweaks open the cracks: social power for Clarice the FBI agent, Anna the teacher and Ellie the astronomer is achieved without disavowing the fractures within female psychic life. Struggling to attain Freud's two pillars of sanity for the neurotically afflicted (by which he meant all of us) - fulfilment in work and the ability to love - Foster's women often succeed in the first but fail in the second by pressing desire back into its place (all those anxious sexual refusals, all that bitten-down fear). Anna, as the King puts it, is able to be, separately, "A mother, a teacher, a widow, but you're never just a woman." This is perhaps another way of saying that Foster's women are representations of contemporary femininity, having work without love, or love without work, but seldom both.

Picking open memory

I suspect this is why women like Foster so much: her grown-up characters

are mired in family, emotion and memory, however disinterested their

professionalism. Though not determined solely by the domestic, the

sexual or the personal, they are marked by a recognition that women

rarely slip into authority without the barbs of sexuality sticking.

For all her adult resourcefulness, Starling's characterisation is

based on the revelation of buried horrors, the unassimilated memory

of those doomed lambs on her uncle's farm, screaming like children.

It's not hard to see Anthony Hopkins' Hannibal Lecter as a demonic

shrink, confronting the adult Clarice with the child beneath as

he picks open memory as if it was a badly healed sore. Ellie's brilliant

astronomical career in Contact is predicated on the intimate

scenes between the child Ellie and her now dead lone-parent father

which open the film and punctuate her adult progress in flashback.

When she finally meets her extra-terrestrial, having journeyed (perhaps)

to Vega, it takes the physical form of this cherished father. However

ambitious your quest, you still confront the repercussions of the

buried family, the past self, its undead griefs. However grown-up

Jodie Foster gets, the child will always be mother to the woman.