Festival postcard

Abandon Normal Devices:

Near chaos and a happy ending

Night Fishing

Abandon Normal Devices Festival of New Cinema and Digital Culture

Liverpool, UK

September–October 2011

Sender: David Sorfa

Abandon Normal Devices positions itself somewhere between gallery opening, art event, club night, hipster ‘happening’ and film festival. It’s not based in a single city, nor does it have an absolute set of dates: in its three years to date the main event has alternated between Liverpool and Manchester, with ancillary events at other times taking place around the North-West.

Not only does AND champion a certain notion of experimental art, its very structure aims to upset received notions of what an art or film festival is supposed to be. This year’s Liverpool session took place in traditional art galleries, the FACT centre and other venues ranging from the abandoned Pilkington glass factory to Bold Street’s Leaf teashop. While it has an overarching interest in the moving image – from computer games to experimental shorts to more traditional feature films with requisite Q&As – its events range from one-off vinyl recordings made onto X-ray sheets (viz Forest Swords at the Static Gallery) to stroboscopic retinal projections in a smoke-filled gallery (Kurt Hentschläger’s Zee, which is a bit like a genuinely working version of William Burroughs’s Dream Machine).

This disparate presentation sometimes teeters on the edge of chaos but somehow never quite loses focus; it’s a pleasure being invited to follow your own proclivities. I learned on the third day that the festival had an overall theme, ‘Belief’, but sometimes these things are better discovered than over-zealously signposted.

While the short film programmes presented the usual gamut of adolescent experimentation, cod-mystical shamanism and retro-futuristic computer graphics, Park Chan-wook’s iPhone-shot kaidan-ghost film Night Fishing showed an astonishingly varied visual sensibility and keen genre understanding, evoking eerie Japanese films like Onibaba (1964) and the nightmarish world of Woman of the Dunes (1964). The disturbing fishing with barbed hooks harks back to the more unpleasantly graphic scenes in Kim Ki-duk’s The Isle (2000), but Night Fishing is a remarkable work of hallucinatory ritual that quickly transcends the novelty value of its low-fi production.

Piercing Brightness

Money was conspicuous by its absence in Elmina (2011), a feature-length Ghanaian melodrama funded by and starring American installation artist Doug Fishbone, but written and directed by Emmanuel Apea, Jr. and co-written by Apea’s brother John, Jr. Fishbone’s only authorial imposition on the local team was that his whiteness not be explicitly referenced in the film.

Elmina draws a fine line between irony and celebration, and while its craftsmanship is excruciating, it is not condescending. The picture appears to be of VHS quality and the sound suffers wild variations of texture and dynamics. The actors are spectacularly unconvincing with Fishbone only just discernible as the rank amateur.

The plot itself is somewhat Shakespearean as a corrupt chieftain descends into madness as he tries to convince the townspeople to sell off their land to a Korean oil company. Ghosts, corruption and cuckoldry, staples of Ghanaian and Nigerian films, abound. It will be interesting to see how Elmina fares in the North African market; it’s certainly unlikely to move beyond a gallery curiosity elsewhere in the world.

The two most successful films at the AND Festival were the Southern gothic Septien (2011) and the 45-minute preview of artist and dangerous intellectual Shezad Dawood’s Piercing Brightness (the latter due for release in 2012). Both had strong and, dare one say, traditional narratives, while every frame is composed with careful sensibility.

The short cut of Piercing Brightness, presented with live accompaniment by Japanese space-rock luminaries Acid Mothers Temple, referenced 1970s structuralist cinema and the delirious excesses of Derek Jarman and Peter Greenaway while presenting a distinctly E.T.-like story of aliens returning to earth to gather previous colonists for a glorious return. Dawood’s visual acuity gives this science-fiction premise an otherworldy timbre which may just help it cross over from the art world into cult cinema.

Septien

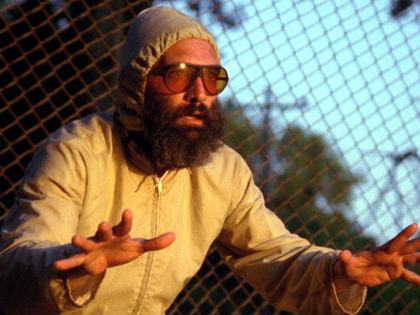

Septien, directed by prolific film critic Michael Tully, is a surprisingly gentle take on the twisted family politics of a dysfunctional trio of brothers. One obsessively produces coprophagic yet somehow cheerful paintings, another cleans, cooks and mothers all and sundry, while the third, played with a beard of immense conviction by Tully himself, huffs petrol, feels sorry for himself but still manages to play better tennis than the pros.

Both Septien and Piercing Brightness offer a vision of redemption which is not based on belief but rather on the inherent promise of fiction itself: that there will indeed be a happy ending.

See also

Quick cuts and slow change: Laura Allsop on UK experimental filmmaking and the Arts Council funding cuts (June 2011)

Tropical rocket: Tony Rayns on Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Phantoms of Nabua at the inaugural AND festival (September 2009)

Invisible classics: Mark Cousins on the masterworks of African cinema (February 2007)