Festival postcard

Dark days: post-Soviet realism at Tallinn’s Black Nights Film Festival

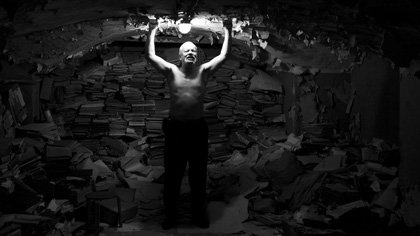

Veiko Õunpuu’s The Temptation of St. Tony

Black Nights Film Festival

Tallinn, Eastonia

December 2010

Sender: Carmen Gray

Perched up by the Gulf of Finland, Estonia’s capital is, at this time of year, dark for all but a few hours daily, providing an alluring promotional hook for its so-named Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival. The event’s wolf logo also milks the notion of an untamed hinterland – a mode of romanticism apt for a tiny Baltic nation which has emerged intact from years of bullying expansionism by European neighbours.

But following the initial euphoria of independence, Estonia is now, like Latvia and Lithuania, ambivalently struggling with its identity in the face of capitalism’s disillusioning realities – a grim state of post-Soviet unease that infuses the region’s current cinematic output. Given this, the crass commercialism of Tallinn’s huge ‘Coca-Cola Plaza’ multiplex, jarringly set against the city’s snow-capped and spired old-town quaintness, couldn’t have provided a more suitable viewing atmosphere.

Now in its 14th year, the festival – built up under director Tina Lokk’s sure hand – offers a wide-ranging programme. Regrettably short on time to sample the Finnish Focus or tempting Czech New Wave retrospective, I looked to the Baltic Feature section as the festival’s main point of distinction. The robust count of 17 films proved deceptive, being bulked up by a slew of mostly TV-length, sub-par documentaries. Still, the content of some – such as Is it Easy to Be…? After 20 Years from Latvia’s Antra Cilinska, which revisits the everyday subjects of Juris Podnieks’ Is It Easy To Be Young (1986) to discover how their aspirations have fared, provided backdrop social texture to the section’s key features.

The one strikingly accomplished documentary was Latvian director Andris Gauja’s Family Instinct, a portrait of rough-as-guts 28-year-old Zanda, whose incestuous relationship with her brother sees him thrown in jail and her shouldering the kid-raising in the chaos of an alcohol-sodden village. Intimately playing out like gripping fiction, it tinges its picture of rural Latvian decay with a unique tender humour, even as it shocks with the bleak extent of the social rot it captured.

Eastern Drift

Desperate dead-end existence also preoccupied Lithuanian director Sharunas Bartas’ Eastern Drift. Through dingy night cityscapes it follows the grim fortunes of Gena, who works for the Russian mafia in Vilnius and dreams of moving west, and his old flame Sasha, an emotionally fragile high-class prostitute he bumps into after heading to Moscow for a cash pick-up which goes drastically wrong. Empathy-tinged rather than glorifying, the film is shot and scored with a piercing melancholy, and delves deeper than its typical gangster plot set-up to critique the lawless opportunism engendered by the Soviet collapse.

While this was a solid, safe choice for the section’s Best Film, by far the better Baltic film was Estonian director Veiko Õunpuu’s complex and esoteric The Temptation of St. Tony, which at least won the FIPRESCI critics’ prize.

Stunningly shot in black-and-white in the vein of Bela Tarr, the film takes its title from the Hieronymous Bosch painting, offering a similarly grotesque, hellish vision of contemporary post-Soviet society. Its namesake is a set-upon middle-manager in existential crisis after his father dies and his boss orders him to fire his factory workers. Tempted to act morally but entrapped in an economy-revering system which contains space for nothing outside self-interest, his world starts to unravel, and after finding a pile of severed hands in the woods, he’s subjected to increasingly bizarre occurrences or visions.

In its absurdist black humour, mystical surrealism, jibes at bourgeois vacuity and atmosphere of institutionalised victimisation it’s thick with influences from Kafka through Buñuel to Lynch, but these derivative elements are together much more than the sum of their parts, and are placed in service to distinctly post-Soviet terrain.

The Temptation of St. Tony

“Capitalism is almost naked in former states that belonged to the USSR, so the problems of capitalism are most apparent here,” Õunpuu said, espousing a Žižek-style view that global capitalism is in inevitable systemic breakdown.

I’d taken the short early-morning flight out to visit him on the snow-deep Estonian island of Saaremaa, where The Temptation was partly filmed and where the uncompromising former painter lives with just his dog in the stove-heated wooden shack, built in 1918, in which the film’s funeral wake was shot. Having sold his apartment in Tallinn, he now fills days meditating, designing greenhouses and striving to perfect mandala geometry art. The set-up couldn’t be farther from brash consumerism; when I visited he didn’t even have running water (tradesmen had been promising to come for weeks).

“This Tony character is something that I could have been and I’m happy to say I didn’t become,” he said, having himself studied economics before dropping with “instinctual moral disdain.” This “strange, neurotic relationship to capitalism”, which he’d yearned for only to find it wasn’t the “salvation” he’d hoped, Õunpuu said is typical of his generation – and, the festival testified, to its cinema.

See also

Perestroika reviewed by Chris Darke (October 2010)

To Get to Heaven First You Have to Die reviewed by Michael Brooke (December 2008)

East of Eden: Dina Iordanova on nostalgia for Communist GDR days in the political satire Goodbye, Lenin! (August 2003)

Werckmeister Harmonies reviewed by Jonathan Romney (April 2003)

Buttoners reviewed by Julian Graffy (March 1999)