The Film Book poll

The best film books, by 51 critics

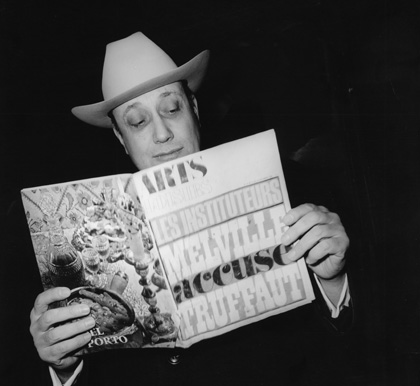

Jean-Pierre Melville

Which are the most inspirational five books about film ever written? This was the question we asked 51 leading critics and writers, and their answers are printed here in full

» Read Nick James’ introduction

Note: Publication dates are for first edition only, except where specified. However, votes for a particular title are collected together no matter what the edition (with the exception of Geoff Dyer’s voting for all five editions of David Thomson’s A Biographical Dictionary of Film).

Geoff Andrew (Head of film programme, BFI Southbank, UK)

Signs and Meaning in the Cinema

By Peter Wollen, Secker & Warburg, 1969

A Biographical Dictionary of Film

By David Thomson, Secker & Warburg, 1975

Hitchcock’s Films

By Robin Wood, A.S. Barnes & Co, 1965

The Making of Citizen Kane

By Robert L. Carringer, University of California Press, 1985

Mamoulian

By Tom Milne, Thames & Hudson, 1969

Michael Atkinson (Critic, USA)

The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968

By Andrew Sarris, Doubleday, 1968

A Biographical Dictionary of Film

By David Thomson

Vulgar Modernism

By J. Hoberman, Temple University Press, 1991

Agee on Film: Reviews and Comments

By James Agee, McDowell, Obolensky, 1958

Magic and Myth of the Movies

By Parker Tyler, Simon & Schuster, 1970

PLUS:

Cahiers du cinéma: The 1950s Edited By Jim Hillier

Confessions of a Cultist By Andrew Sarris

The Phantom Empire By Geoffrey O’Brien

Durgnat on Film By Raymond Durgnat

Science Fiction Movies By Philip Strick

The Hollywood Hallucination By Parker Tyler

Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies By Manny Farber

The Shadow of an Airplane Climbs the Empire State Building By Parker Tyler

Film as a Subversive Art By Amos Vogel

Dictionary of Films By Georges Sadoul

Cinema: A Critical Dictionary Edited By Richard Roud

On the History of Film Style By David Bordwell

City of Nets By Otto Friedrich

Visionary Film By P. Adams Sitney

Hitchcock By François Truffaut

Who the Devil Made It By Peter Bogdanovich

Signs and Meaning in the Cinema By Peter Wollen

Peter Biskind (Author/critic, USA)

The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era

By Thomas Schatz, Pantheon Books, 1988

I Lost It At the Movies

By Pauline Kael, Little, Brown, 1965

Final Cut

By Steven Bach, William Morrow, 1985

Indecent Exposure

By David McClintick, William Morrow, 1982

A Life

By Elia Kazan, Alfred A. Knopf, 1988

Edward Buscombe (Critic, UK)

Signs and Meaning in the Cinema

By Peter Wollen

The founding work of so-called Screen theory – which is where I came in, although it has now left me behind, or me it – is still a pretty enjoyable read today. Back in 1969 when it was first published, it was, like Martin Peters, ten years ahead of its time.

Hitchcock’s Films

By Robin Wood

Its opening sentence – “Why should we take Hitchcock seriously?” – strikes just the right note of courteous provocation in its determination to reorient our view of popular cinema. Although I disagree with much of it, Wood always demands to be taken seriously.

The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968

By Andrew Sarris

The Bible of the dedicated cinephile when it was first published in 1968, and still an invaluable route map of what needs to be seen.

Horizons West: Studies in Authorship in the Western

By Jim Kitses, Thames & Hudson, 1969

Here I have to declare an interest, in both senses: an enduring love of the Western, and a role in editing the much-expanded second edition of 2004. The best book of criticism bar none on the most important film genre.

The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era

By Thomas Schatz

First published in 1988, and thus the only one of my choices not first published in the 1960s (showing my age). A marvellously subtle and informative account of the way the Hollywood film industry worked in its heyday and a book I wish I’d been able to write myself.

Michael Chanan (Academic, UK)

The Technique of Film Editing

By Karel Reisz and Gavin Millar, Focal Press, 1953

This is the book that taught me about film language – not just the nuts and bolts of how it works, but the aesthetics. But I forgot that I’d read it (as an undergraduate, when I was first thinking of making films) until many years later, when I first started teaching film and rediscovered it. Now I recommend it to all my students, whether they’re interested in practice or theory.

The World Viewed

By Stanley Cavell, Viking, 1971

A book I found so captivating I devoured it in a single night. As a postgrad studying aesthetics, I was enthralled to find an English-language philosopher who understood cinema! At the end I felt it had said practically everything it needed to say. An exaggeration, of course, but for a while I was convinced.

The Camera and I

By Joris Ivens, International Publishers, 1969

Like all autobiographies, Ivens’ leaves certain things out, but it’s a great testimony to political commitment and full of wisdom about the nature of documentary, which Ivens calls “a creative no-man’s land”. Very inspiring.

Hitchcock

By François Truffaut, Simon & Schuster, 1967

I enjoyed this immensely, though largely because it seemed to me to explain why I didn’t really care much for Hitchcock.

Histoire économique du cinéma

By Pierre Bachlin, La Nouvelle Edition, 1947

I found this browsing for second-hand film books in Paris at the very moment I was first trying to figure out how the film industry worked. Bachlin was a Marxist, and this was the first rigorous analysis of the industry I’d discovered that made real sense to me. It seems symptomatic that the book has never been translated into English – neither has the film writing of the Italian Marxist Umberto Barbaro (which I read in the translation published in Cuba by the ICAIC).

Tom Charity (Lovefilm and CNN.com, Canada)

Hitchcock’s Films

By Robin Wood

Hitchcock

By François Truffaut

These were the most inspirational books to me as a film student (as was Truffaut’s The Films in My Life). If the first edition of Robin Wood’s study hadn’t been so seminal for me, I would now choose Hitchcock’s Films Revisited, because it shows how critical engagement is a lifetime’s process, always evolving as we mature. The Hitchcock interview book has probably inspired more film books than any other, including, I assume, the entire Faber ‘Directors on Directors’ series.

This is Orson Welles

By Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum, HarperPerennial, 1992

This is probably my favourite of the many books on Welles.

John Ford: The Man and His Films

By Tag Gallagher, University of California Press, 1986

Substantially revised in 2007 and made available for free download, this is exemplary film criticism, a book Ford would have delighted in deriding yet kept close by his bed, I’m sure.

A Biographical Dictionary of Film

By David Thomson

But let’s have the original 1975 edition, when it was really something.

Ian Christie (Professor of Film History, Birkbeck, UK)

Frank Kermode defined the ‘classic’ in literature as a work that can be endlessly re-interpreted, according to the needs and interests of successive generations. These are the books that I find myself returning to again and again, usually finding new information and insights that I hadn’t previously noticed.

Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Cinema

By Jay Leyda, Allen & Unwin, 1960

Surely one of the greatest books about a national cinema ever written? Leyda spent several years in the USSR in the mid-30s, studying at the world’s first film school, and assisting Eisenstein on his eventually banned film, Bezhin Meadow. And those ‘witnessed years’, as he calls them, are the fulcrum of the book. But the whole sweep of Russian cinema up to the years just after Stalin’s death are vividly chronicled by Leyda. We may know much more today about what really happened, but Leyda’s judgements were shrewd and his sheer enthusiasm is still infectious.

The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968

By Andrew Sarris

The book that every young film snob carried around or even memorised in the early 70s – just in case you might catch a rare Edgar Ulmer B movie in a rep cinema (yes, that’s how we saw films maudits in those days). Sarris’ classification of directors on different levels – from the 'Pantheon' to ‘Lightly Likeable’, via ‘Expressive Esoterica’ and ‘Less than Meets the Eye’ is imprinted on my attitude to American cinema, and I still have to argue in my head with Sarris’ unforgettably snappy put-downs. Sarris was far more influential than Chabrol, Truffaut and co., I’m sure, in shaping the British politique des auteurs.

What is Cinema?

By André Bazin, translated by Hugh Gray, University of California Press, 1967 (Volume 1) and 1971 (Volume 2)

This may be a poor translation of Bazin, inadequately edited, but it was my generation’s first contact with cinema’s greatest post-war critic-philosopher and the godfather of the French New Wave. After first swallowing Bazin whole, I turned against his Catholic humanism, but I find myself returning to him almost every week to check something, to argue with him, and often to agree.

Circles of Confusion

By Hollis Frampton, Visual Studies Workshop, 1983

Frampton wasn’t just the high priest of ‘structural cinema’, with his cerebral but playful masterpieces, Zorns Lemma and (nostalgia), but a superb essayist on classic photography and on the ontology of film as “the last machine”. This long-unfindable book (now revived in a new edition) brings together essays that can stand alongside those of Borges, Barthes and just about anyone who helped shape it.

A Life in Movies

By Michael Powell, Heinemann, 1986

After years of professional disappointment, Michael Powell decided to write a passionate no-holds-barred autobiography that would tell the story of cinema as the 20th century’s folk art from the standpoint of one who had helped shape it. There’s still no film autobiography to match it for style, audacity and insight – and it deserves to be recognised as one of the 20th century’s great memoirs. Apart from conveying what it felt like to be at the top of the game (and sliding to the bottom in the second, equally fascinating volume, Million Dollar Movie), it also provides dozens of shrewd judgements on film-makers who are only now being discovered.

Five is not enough! It leaves no room to mention Ray Durgnat’s crucial book, A Mirror for England, that staked a claim for British cinema when few film enthusiasts in Britain cared; or Rachael Low’s pioneering seven-volume history of British cinema from the very beginning to, alas, only 1939, although Low is a treasure trove of discoveries still being made. Or Dan Talbot’s eclectic Film: An Anthology (1966), a stirring alternative to Ernest Lindgren and Paul Rotha, which first introduced me to writings by Manny Farber, Parker Tyler, Gilbert Seldes and Erwin Panofsky. Peter Wollen’s Signs and Meaning in the Cinema, as elegantly written as it was groundbreaking, made semiotics exciting and revealed the political and wider aesthetic context of film. And what about the writing that was never in book form when it was most influential? How many Xeroxes of Laura Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasure’ Screen article have I passed on, along with essays by P. Adams Sitney, Annette Michelson and many others, before film books became common?

Michel Ciment (Editor, ‘Positif’, France)

What is Cinema?

By André Bazin

An anthology of the best French film critic of the 1940s and ’50s.

Hitchcock

By François Truffaut

A groundbreaking interview book and a model of its kind.

A Life

By Elia Kazan

The best autobiography (with Bergman’s) of a theatre and film director.

Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood

By Todd McCarthy, Grove Press, 1997

A perfect example of the critical biography: informed, never complacent, analytical and with a superb knowledge of the industry background.

Viv(r)e le cinéma

By Roger Tailleur, Institut Lumière, 1997

Personal Views: Explorations in Film

By Robin Wood, Gordon Fraser, 1976

Two volumes of selected film criticism by two inspirational critics, from France and England respectively.

Kieron Corless (Deputy Editor, ‘Sight & Sound’)

Abel Ferrara

By Nicole Brenez, University of Illinois Press, 2006

Poétique du cinématographe

By Eugène Green, Actes Sud, 2009

Notes on the Cinematographer

By Robert Bresson, Editions Gallimard, 1975

Fassbinder’s Germany

By Thomas Elsaesser, Amsterdam University Press, 1996

Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies

By Manny Farber, Da Capo Press, 1998 (expanded edition)

Mark Cousins (Critic and filmmaker, UK)

Who the Devil Made It?: Conversations with Legendary Film Directors

By Peter Bogdanovich, Alfred A. Knopf, 1997

The Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema

Edited By Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willemen, BFI, 1994

Notes on the Cinematographer

By Robert Bresson

Currents in Japanese Cinema

By Tadao Sato, Kodansha Int, 1982

Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis

By Barry Salt, Starword, 1983

Paul Cronin (Writer/film-maker, UK)

On Directing Film

By David Mamet, Viking, 1991

A beautiful, idiosyncratic articulation of the job of the film director. Eisenstein for the new millennium.

The Technique of Film Editing

By Karel Reisz and Gavin Millar

There is no better explanation of what it’s all about. Theory and practice intersect at craft.

My Life and My Films

By Jean Renoir, Collins, 1974

Autobiography and common sense.

Film: A Montage of Theories Edited

By Richard Dyer, MacCann, E.P. Dutton, 1966

A definition of film theory: anything written about the cinema.

Film as a Subversive Art

By Amos Vogel, Random House, 1974

Because he has spent the past 60 years opening up new worlds to us.

Chris Darke (Critic, UK)

The Republic

By Plato

Cinema was invented in the fourth century BC with the ‘Myth of the Cave’, a thought experiment illustrating the hard-won virtues of education via a parable of perception and knowledge. Socrates’ mise en scène depicts underground captives facing a wall on which the light of a fire casts lifelike shadows, which they mistake for reality. The question of whether we should believe our eyes (or any of our senses) is dramatised in a setting that uncannily predicts cinema. ‘The Cave’ is the first work of film theory, and considerably more readable than most examples of the genre written since.

Illuminations

By Walter Benjamin, Suhrkamp Verlag, 1955

For ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1936), a jazz standard of an essay that writers have riffed on (and ripped off) ever since. Benjamin was one of the first people to grapple with the question of how art is transformed by technology, supposedly sacrificing ‘aura’ for accessibility. A modernist rapture over the possibilities of the film image – deathlessly described as “an orchid in the land of technology” – is palpable throughout.

What is Cinema?

By André Bazin

In his clarity of expression and the way he develops theoretical ideas from specific examples, Bazin was a truly great writer on cinema. Two essays from the 1940s are irreplaceable, ‘The Ontology of the Photographic Image’ and ‘The Myth of Total Cinema’, both setting film in art’s longue durée. Should one want to get a handle on the thorny philosophical question of ‘faith’ in the image in the digital era, Bazin is the first go-to guy…

The Society of the Spectacle

By Guy Debord, Buchet-Chastel, 1967

…and Debord is the second. Platonic mistrust of mere appearances goes into late-1960s overdrive here, but Debord’s analysis remains astonishingly prescient given that the spectacle – described as “the other side of money” – is now the element we live in. And while cinema is inevitably compromised by its fundamental role in this state, it should be remembered that Debord was also a master of the found-footage film.

The Invention of Morel

By Adolfo Bioy Casares, Editorial Losada, 1940

There’s no shortage of novels deserving of a place on the shelf, including Shoot! Or the Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio by Luigi Pirandello (1916), pretty much everything by Don DeLillo, and Me, Cheeta by James Lever (2008). Three rules for great novels about film: 1) they needn’t be ‘great novels’; 2) they should concern themselves less with the intrigues of film-making than with cinema as a metaphor for the modern condition; 3) they must remain resolutely unfilmable. Which ought to rule out The Invention of Morel, the inspiration for Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad. Bioy Casares was a friend and collaborator of Borges, and his 1940 fantasy shares his quizzically metaphysical character and was inspired by the author’s Louise Brooks fixation. A fugitive finds his way to an unnamed island, discovers he has unexpected company, sees two suns rise, and observes how, with the aid of Dr Morel’s magical machine, space and time can be irretrievably altered. Borges called the plot “perfect” – if it was good enough for him, it’s good enough for me.

Maria Delgado (Academic, UK)

Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema

By Andrei Tarkovsky, The Bodley Head, 1986

Poetry as cinema, cinema as poetry. One of the best books on artistic endeavour and the craft of film-making. Just beautiful.

Out of the Past: Spanish Cinema After Franco

By John Hopewell, BFI, 1986

The first book to really explore what had happened to Spanish cinema post-Franco, rooting the argument in a discussion of how film-making had functioned under El Caudillo’s dictatorship. Still indispensable.

Letters

By François Truffaut, translated by Gilbert Adair, Faber & Faber, 1989

A funny, droll, incisive, idealistic and perceptive collection of letters to friends and collaborators, colleagues and film-makers he admired (and fell out with).

The Brechtian Aspect of Radical Cinema

By Martin Walsh, edited by Keith Griffiths, BFI, 1981

I picked it up as an undergrad and never looked back.

Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society

By Richard Dyer, BFI, 1986

The first edition was published in 1986 and changed the way I thought about film acting and stardom.

Geoff Dyer (Author, UK)

A Biographical Dictionary of Film

By David Thomson

I would restrict my choice to the various editions (the fifth, I believe, is forthcoming) of David Thomson’s A Biographical Dictionary of Film. I’m sure some future scholar will produce an admirable thesis comparing the changes in – and evolution of – what has come to be, along with everything else, a vicarious and incremental autobiography. In that context, even Thomson’s diminishing interest in cinema – or current cinema at any rate – becomes a source of fascination. The Dictionary is not only an indispensable book about cinema, but one of the most absurdly ambitious literary achievements of our time. It deserves a shelf to itself.

The Ferroni Brigade aka Christoph Huber & Olaf Moller (Critics, Austria/Germany)

Dictionnaire du cinéma

Edited by Jacques Lourcelles, Laffont, 1993

The only general dictionary we trust: absolutely partisan while commendably catholic in its scope and taste – just check out the list of auteurs worth discussing more deeply at the very end of the second edition from 2003.

Lignes d’ombre: une autre histoire du cinéma soviétique (1926-1968)

Edited by Bernard Eisenschitz, Edizioni Gabriele Mazzotta, 2000

Histoire du cinéma Nazi

By Francis Courtade and Pierre Cadars, Eric Losfeld/Éditions Le Terrain Vague, 1972

Two tomes that (should have, at least) changed the way we think about film history; two attempts to understand the (extra)ordinary in film cultures deemed totalitarian and therefore artistically irrelevant by our unquestioning middlebrow culture and its collaborators high and low.

Enciclopédia do Cinema Brasileiro

Edited by Fernão Ramos and Luiz Felipe Miranda, Senac São Paulo, 2000

Anschluß an Morgen and Das tägliche Brennen

By Elisabeth Büttner and Christian Dewald, Residenz Verlag, 1997 and 2002

Two exemplary ways of making sense of a national film culture: the first is an encyclopedia that invites the seeker to find his or her own way through a labyrinth of myriad relationships; the second offers creative criss-cross readings of topoi and obsessions through various decades, genres and political systems. We consider these approaches preferable to the common and-then-and-then histories, as these are usually too industry-development-keyed – i.e. disinterested in spheres like documentary cinema, the avant garde, sponsored films, amateur praxis, etc, which we consider all equal in importance and interest.

Mauritz Stiller och hans filmer 1912-1916

By Gösta Werner, Norstedt, 1969

Leo McCarey: sonrisas y lágrimas

By Miguel Marías, Nikel Odeon, 1999

The value of the late Gösta Werner’s work lies in its author’s age: he was old enough to have seen many a Stiller work now (considered) lost, meaning his memories are probably as close as we’ll ever get to these films. Marías’ McCarey monument is of interest and dear to us as an instance where the best analysis of an essential oeuvre was written and published in a language other than that of the auteur in question.

Soshun: Früher Frühling von Ozu Yasujiro

By Helmut Färber, Eigenverlag des Autors, 2006

Red Cars

By David Cronenberg, Volumina, 2006

Put them in your apartment and feel the atmosphere change for the better. Soshun is the most outstanding piece of film analysis in decades – based on only the first few minutes of the subject’s work.

Zur Kritik des Politischen Films: 6 analysierende Beschreibungen und ein Vorwort “Über Filmkritik”

By Peter Nau, DuMont Buchverlag, 1978

Der lachende Mann: Bekenntnisse eines Mörders

By Walter Heynowski and Gerhard Scheumann, Verlag der Nation, 1966

Criticism and agitation, reflection and documentation, theory and praxis.

Lizzie Francke (Development Producer, UK Film Council, UK)

Notes on the Cinematographer

By Robert Bresson

On Film-making

By Alexander Mackendrick, Faber & Faber, 2004

The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era

By Thomas Schatz

The Cinema Book

Edited by Pam Cook, BFI, 1985

Suspects

By David Thomson, Secker and Warburg, 1985

Philip French (Critic, ‘Observer’, UK)

Film

By Roger Manvell, Pelican, 1944

There was only a handful of books on the cinema when I and my contemporaries (now aged 70+) became cinephiles after World War II: Paul Rotha’s seminal The Film Till Now (1930 and never updated by its author); Alistair Cooke’s lively anthology of criticism, Garbo and the Night Watchmen; several theoretical works (Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Spottiswoode, Balázs, Arnheim); some dull sociological studies; and Manvell’s Pelican paperback Film. First published in 1944 and constantly revised over the next decade, Manvell’s marvellous book covered all aspects of cinema and was the one book that all of us owned. Affordable, deeply serious, clearly written, it gave us our first filmographies, 15 frame blow-ups from Battleship Potemkin and a cinematic canon that we eagerly accepted and then rebelled against.

Hitchcock’s Films

By Robin Wood

When this original paperback appeared in 1965, the first full-length study of Hitchcock in English, I wrote in my Observer review: “It is an important publication that sets an altogether new standard for critical books on the cinema in this country.” Revised and augmented several times (most recently in 1989), it remains unsurpassed and is the high-water mark of auteurist criticism, with Andrew Sarris’ taxonomic masterpiece The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 a close runner-up.

The Parade’s Gone By

By Kevin Brownlow, Secker & Warburg, 1968

Few people have done so much to revive interest in silent cinema and none has written so well about it as Brownlow. This beautifully produced book, the first and most essential volume in a trilogy on American cinema before the coming of sound, is based entirely on evidence gathered at first hand and mostly illustrated by photographs from the author’s own collection. It’s an informative delight to read and look at and the kind of thing that gives passionate enthusiasm a good name.

The Film Encylopedia

Edited by Ephraim Katz, Crowell, 1979

First published in 1979, this is by some way the best, most wide-ranging single-volume reference book on the cinema ever written. Entirely the work of one man, an Israeli documentarist resident in New York, it has been updated, though sadly not improved, since Katz’s untimely death at the age of 60 in 1992. It should be kept within easy reach by anyone interested in the cinema, whether writer or film fan.

The Last Tycoon

By F. Scott Fitzgerald, Scribner, 1941

The cinema as a subject for fiction has attracted serious writers ever since Luigi Pirandello’s Shoot! was published in 1915, and there are 50 or 60 examples on my shelves, gathered over the years for a book I’ll now never write. The best novel of recent years is Theodore Roszak’s astonishing Flicker (1991), while the finest on British cinema is Christopher Isherwood’s Prater Violet (1945), but greatest of all is Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon, left unfinished at his death in 1940 and superbly edited by his friend Edmund Wilson.

Chris Fujiwara (Critic, US)

Rivette: Texts and Interviews

Edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum, BFI, 1977

A manifesto for a revolutionary cinema, this compact selection of talks with and essays by Jacques Rivette includes his seminal text on Fritz Lang’s Beyond a Reasonable Doubt.

Godard on Godard

By Jean-Luc Godard, edited and translated by Tom Milne, Secker & Warburg, 1972

It may not always be obvious from reading Godard’s early reviews that the writer would become a film-making giant, but it’s clear he could inspire five or six others to do so.

Notes on the Cinematographer

By Robert Bresson

Every page of this slim volume – the Pascal’s Pensées of film – is filled with riches. Opened at random: “To your models: ‘You must play neither someone else, nor yourself. You have to play no one’”; “Neither director, nor film-maker. Forget that you’re making a film”; “Slow films in which everyone gallops and gesticulates; quick films in which people hardly move”; “Your film must be like the one you see while shutting your eyes.”

The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968

By Andrew Sarris

It launched and defined an era of cinephilia in the United States.

Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies

By Manny Farber

The only reason I list this edition instead of 2009’s Farber on Film: The Complete Film Writings is that the smaller collection is the one I spent years marveling at, puzzling over and taking comfort from as from a favourite food.

Graham Fuller (Critic, USA)

The Parade’s Gone By

By Kevin Brownlow

The History of World Cinema

By David Robinson, Stein and Day, 1973

The Haunted Screen

By Lotte Eisner, Le Terrain Vague, 1952

A Biographical Dictionary of Film

By David Thomson

Suspects

By David Thomson

Working on The Movie, a multi-volume history of the cinema published in weekly parts at the start of the 1980s, I found the first four books on this list not only remarkable for their scholarship and practical use, but as sources of magic – Eisner’s not least because of the dread-heavy stills and the electrifying chapter on G.W. Pabst and Louise Brooks, since exceeded only by ‘Lulu and the Meter Man’ in Thomas Elsaesser’s Weimar Cinema and After. Though in need of updating, Robinson’s History is unequalled as a single-volume narrative primer on cinema’s evolution. The Parade’s Gone By is the most accessible of Brownlow’s great books about silent film, though I could as easily have picked The War, the West and the Wilderness and Behind the Mask of Innocence.

Thomson’s Dictionary was a revelation when it first appeared 35 years ago because it doubled as a work of reference and (brilliant) criticism – it remains indispensable. Thomson was a historian writing like a novelist and so it was logical that he would eventually weave fiction with history in the serpentine Suspects, from which one can learn more about the iconography of film noir than from many worthy textbooks.

That’s five – and still I’m missing The BFI Companion to the Western and Hollywood Babylon.

Charlotte Garson (Critic, ‘Cahiers du cinéma’, France)

Hitchcock

By François Truffaut

Encompasses all film book categories: interview, yes, but also memoir, monograph, theory, picture book…

What is Cinema?

By André Bazin

It’s always fruitful to go back to Bazin’s writings, less as a theoretician than as a critic (with theoretical intuitions that are sometimes hazardous).

Notes on the Cinematographer

By Robert Bresson

The first film book I ever read.

Eric Rohmer

By Pascal Bonitzer, Cahiers du cinéma, 1991

Along with Bazin’s unfinished Jean Renoir this is one of the best monographs I know on any director.

Film: A Sound Art

By Michel Chion, Columbia University Press, 2003

PLUS:

Godard au travail: Les années 60 By Alain Bergala

A wealth of documents, but also Alain Bergala’s ever-clear, precise prose on one of the film-makers he knows best. (Also, in French: Nul mieux que Godard, an anthology published by Cahiers du cinéma on Godard and edited by Bergala.)

La Maison et le monde By Serge Daney

The anthology (in two volumes) of the Cahiers and Liberation French critic offers a panoramic view of the changes French criticism went through from the 1960s to the ’90s.

My Life and My Films By Jean Renoir

Beauty and the Beast: Diary of a Film By Jean Cocteau

The ‘I’ of the Camera: Essays in Film Criticism, History, and Aesthetics By William Rotman

John Ford hors-série, Cahiers du cinéma

Mikio Naruse By Jean Narboni

Sul cinema By Roland Barthes, edited by Sergio Toffetti

Only in Italy are Barthes’ writings on film collected!

Tom Gunning (Professor of Cinema and Media Studies, University of Chicago, USA)

What is Cinema?

By André Bazin

Film Form

By Sergei Eisenstein, edited and translated by Jay Leyda, Harcourt Brace, 1949

Visionary Film

By P. Adams Sitney, OUP, 1974

The World Viewed

By Stanley Cavell

From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film

By Siegfried Kracauer, Princeton University Press, 1947

Philip Horne (Academic, UK)

Prater Violet

By Christopher Isherwood, Methuen, 1945

The best novel I know on the film-making process, set in the 1930s and dealing (as if from the experience of ‘Christopher’ himself) with the career of Austrian director Friedrich Bergmann, whose genius is thrillingly evoked.

Hitchcock

By François Truffaut

One of the great landmarks, a meeting of two film cultures, two languages, two personalities – full of omissions and evasions, but richly suggestive, and a demonstration that criticism and creation can enter into a significant dialogue.

A Life in Movies

By Michael Powell

Powell was a major film-maker who could write and who cared immensely and generously for literature and art – this magnificently vivid, self-dramatising yet wonderfully responsive first volume of his memoirs brings to life one eccentric but steely Englishman’s journey to greatness.

Adventures of a Suburban Boy

By John Boorman, Faber & Faber, 2003

Like Powell, Boorman can write like a dream as well as direct films like Point Blank and Deliverance “in a state of grace”, and this wise, intensely sympathetic, informative, amusing, moving account of his globe-spanning trajectory from Carshalton via L.A. to Galway is a classic.

A Biographical Dictionary of Film

By David Thomson

After three decades of use, it’s an old companion, rather taken for granted and occasionally irritatingly prejudiced (eg on Ford), as well as funny and endlessly suggestive about avenues to explore; but whatever reservations it inspires (and expresses) it’s a grand example of appreciative, impassioned, intelligent, encyclopaedic criticism that shaped a generation or two of film watchers.

Kevin Jackson (Writer, UK)

Godard on Godard

By Jean-Luc Godard

A thrilling confection of passionate advocacy, youthful extremism, ardent love and lofty disdain. The one film book I crammed into my suitcase to keep me company when I went to live abroad for a couple of years; every dip into its pages offered something to think about, wonder at or silently dispute. So what if it borders on eccentricity, and then crosses the borders? It turns up the old mental rheostat every time. Well worth it even if you don’t much care for his films, and all the more so if you do.

Hitchcock

By François Truffaut

Doesn’t everyone enjoy these interviews? Highly informative when read innocently, highly entertaining when read for the implied drama: the hero-worshipping young man (who is no dummy, mind), paying court to the urbane old master who seems to give so much away, and yet, cunning trickster/shaman that he is, really yields nothing that could be used in court against him. The dialogue as artform.

Reeling

By Pauline Kael, Little, Brown, 1977

Or almost any of her collections, really, but wasn’t she at her best when she had plenty of movies to love? And wasn’t the 1970s the period of cinema she loved best? This was the volume that made a god awful 26-hour greyhound bus trip to New York seem bearable – in fact, time well spent. It doesn’t matter if you don’t admire all her raving and comminations; she is almost always a gas, and brought to film criticism an addictive combination of driven, garrulous intensity and loose-limbed, slangy intimacy. Has anyone ever managed that balance as well?

A Biographical Dictionary of Film

By David Thomson

A miracle. How could anyone – especially someone with a boring day job, and before the video/DVD age – have seen so much, noticed so much, understood so much, remembered so much at such a young age… and then written about it in a prose style of such idiosyncratic verve, lyricism and aphoristic pith? Not just one of the best film books, one of the best later 20th-century books of criticism of any medium. A monument.

Madame Depardieu and the Beautiful Strangers

By Antonia Quirke, Fourth Estate, 2007

Plus one: this lightly fictionalised memoir of film criticism, love affairs and the quest for beauty and perfection is so funny that it often makes you bark with laughter. Plus two: it is also an achingly serious discussion about why movies can be so potent, about the way they shape our fantasy lives and so our real lives, about how it really does matter whether or not you can love Withnail & I. Plus three: Quirke has an effortless knack for the mot juste; eat your liver, Flaubert. A potent and delicious cocktail.

Nick James (Editor, ‘Sight & Sound’)

Like most people in the unique position of foreknowledge of what others have said, I have avoided the choices that now seem obvious in this survey. My list is therefore devised partly to champion books neglected by everyone else.

A Mirror for England: British Movies from Austerity to Affluence

By Raymond Durgnat, Faber & Faber, 1970

I first encountered Durgnat’s seminal book by proxy in the stirring poetic quotes from it that turned up regularly in the reviews of old British films in London listings magazines. It was out of print by the time I wanted to buy it, but I found a copy on my first trip to New York in 1982 (along with Kings of the Bs), devoured it, then lent it to a friend and never saw it (or him) again. So it’s as mysterious a treasure for me as, say, any film seen and loved years ago and not re-encountered since – though of course there’s a copy in the BFI library just three floors down from my office. Call it deferred gratification.

Melville on Melville

Edited by Rui Noguera, translated by Tom Milne, Secker & Warburg, 1971

This most inspiring of interview texts is at least as fine a demonstration as Truffaut’s Hitchcock of why the Q&A format is so often more revealing than the mediated profile article or book. As befits his flinty films, Melville is a pugnacious, affectionate and slightly melancholy observer: sanguine and unequivocal about the daring with which his films were made. He gives a cool insight too into the rich inheritance of pre-war French cinema that declined post-war into the cinéma du papa so decidedly trashed by Truffaut. Towards the book’s end, Melville says, “I estimate the final disappearance of cinemas to take place around the year 2020.” Let’s hope he’s not right.

The New Wave: Truffaut, Godard, Chabrol, Rohmer, Rivette

By James Monaco, OUP, 1976

Again, for me this book was about self-education. Not at all professionally involved in film when I bought it, I wanted something to help a London art student get more out of the films of Godard, Truffaut, Rohmer, Chabrol and Rivette. And if it was as puzzling in its way as some of the films seemed at the time, then that only intrigued me more, as any introduction to so important a subject should.

The Avant-Garde Finds Andy Hardy

By Robert B. Ray, Harvard University Press, 1995

Judging from this survey few, if any, colleagues seem to share my enthusiasm for Ray’s attempts to break out of the cul-de-sacs of postmodern film theory, but I find his use of surrealist randomising and brainstorming games to generate new perspectives on classic Hollywood and other material stimulating, imaginative, informative and very entertaining, both here and in his more recent The ABCs of Classic Hollywood.

The Material Ghost: Films and Their Medium

By Gilberto Perez, The John Hopkins University Press, 1998

In recent decades there has been no more cogent a rethinking of the physical and psychological experience of film as it evolved, both as a technology and as an artform. I want to read it again, soon.

Kent Jones (Critic, USA)

Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies

By Manny Farber

Farber on Film: The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber

By Manny Farber, Library of America, 2009

King Vidor, American

By Raymond Durgnat and Scott Simmon, University of California Press, 1988

The American Cinema

By Andrew Sarris

Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage

By Stanley Cavell, Harvard University Press, 1981

Hitchcock

By François Truffaut

These are the books that I’ve lived with the longest (excepting Farber On Film), so I suppose they’re the ones that have had the most profound effect on me.

Richard T. Kelly (Author, UK)

Fun in a Chinese Laundry

By Josef von Sternberg, Secker & Warburg, 1965

Notes on the Cinematographer

By Robert Bresson

My Last Breath

By Luis Buñuel, Jonathan Cape, 1983

Beauty and the Beast: Diary of a Film

By Jean Cocteau, J.B. Janin, 1946

Hitchcock

By François Truffaut

Mark Le Fanu (Academic/critic, Denmark)

The books that most influence you tend to come early in one’s life – whether one likes it or not, everyone is a product of their generation. I started reading about cinema in the late 1960s, the heyday of auteurism: the books that I read then formed my taste and have marked me as a certain kind of cinephile and, 40 years on, after the great adventure (or misadventure) of theory, that is still how I would define myself. The opening revelation in my case was the discovery of the late Robin Wood’s writings, specifically the five or six beautiful monographs he wrote around that time on contemporary film-makers, so let me single out Bergman (Praeger, 1969). Wood’s patient, unpedantic, exegetical prose remains for me the permanent model of how to do these things.

Next, an interview book: Jon Halliday’s extended conversation Sirk on Sirk: Interviews with Jon Halliday (Secker & Warburg, 1971) hints at profound connections between European and American cinema and the sophisticated passage between the two cultures – connections deepened and cemented by my more or less simultaneous discovery of Andrew Sarris’ extraordinary handbook (compact and encyclopaedic at the same time) The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968. Over the years this little volume must surely have been the Bible for many of us.

Another bible (can there be two?) that has never left my desk is David Thomson’s A Biographical Dictionary of Film. Readers of Sight & Sound will need no introduction to Thomson’s stunningly erudite film scholarship – for over 30 years he has been a leading contributor to this journal.

Alas, only one more book! There are so many wonderful writers out there. Should I opt for something from my collection written by Geoffrey O’Brien? Or Pauline Kael? Or Robert Warshow? Or André Bazin? Or either of the two wise Gilberts (Perez and Adair)? No, it is going to be François Truffaut’s collection of essays The Films in My Life (translated by Leonard Mayhew, Simon & Schuster, 1978). The peerless lucidity of his writing about cinema is underscored by a profound moral passion. Indeed, this is true about all the writers on film that I admire most – even the aesthetes and dandies.

Toby Litt (Author, UK)

Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema

By Andrei Tarkovsky

Tarkovsky is my all-time favourite director. But while this is fascinating, I sometimes find his statements frustratingly evasive. Or to the point but about very vague subjects: “Time”. Everything’s a lot clearer in the films. Yet this is what he had to say about them, and that makes it uniquely valuable.

Notes: On the Making of Apocalypse Now!

By Eleanor Coppola, Simon & Schuster, 1979

For a while I became obsessed with what must have been the best-documented disaster shoot in film history. I had the photo of Francis Ford Coppola pointing a revolver at his head up on my office wall the whole time I was writing Corpsing.

Louise Brooks

By Barry Paris, Hamish Hamilton, 1989

This depressed the hell out of me, but it’s a great read. Louise Brooks was one of the few actresses with absolute integrity. This may have something to do with why she also had the most vivid screen presence.

Lulu in Hollywood

By Louise Brooks, Hamish Hamilton, 1982

And she could write, too.

Quay Brothers Dictionary

By Michael Brooke

In the absence of a full book on my favourite contemporary film-makers, this pamphlet that came with the DVD Quay Brothers: The Short Films 1979-2003 will do very well. I’m still following up all the references to writers, artists and poster designers.

Brian McFarlane (Academic, Australia)

Agee on Film: Reviews and Comments

By James Agee

I loved his willingness to find excitement in unexpected places, to do justice to merit when he found it and to write in such a strongly personal voice.

Ealing Studios

By Charles Barr, Cameron & Tayleur/David & Charles, 1977

This still seems to me the definitive account of the ethos of a studio. Lucid, rigorous and utterly readable.

David Lean: A Biography

By Kevin Brownlow, Richard Cohen Books, 1996

The best biography of a film-maker I’ve ever read. An enthralling account of a man enraptured by cinema, written by another man enraptured by cinema.

Typical Men: The Representation of Masculinity in British Cinema

By Andrew Spicer, I.B. Tauris, 2001

Gives a whole new perspective on the phenomenon of male stardom in British film, wears its theory lightly and is written with wit and perception.

A Biographical Dictionary of Film

By David Thomson

Infuriating and stimulating by turns, this is an idiosyncratic inclusion. It leaves out Phyllis Calvert and includes Audie Murphy, which enrages me, but I read it from cover to cover.

Luke McKernan (Curator, Moving Image, British Library, UK)

Spellbound in Darkness

Edited by George C. Pratt, University of Rochester, 1966

A loving anthology, with commentary, on the silent cinema. An invitation to discovery on every page, and perhaps the best title for any film book yet published.

The British Film Catalogue, 1895-1970

By Denis Gifford, David & Charles, 1973

The nearest we have to a British national filmography was created not by any institute or university but by one man.

Ealing Studios

By Charles Barr, 1977

A classic analysis of a film studio’s output in terms of nation, society and politics. There is no better stimulus to look at films seriously.

The Pleasure Dome

By Graham Greene, Secker & Warburg, 1972

Greene’s film reviews from the 1930s are filled with sharp observations and haunting turns of phrase no other critical anthology can match.

The Cinematograph in Science, Education and Matters of State

By Charles Urban, The Charles Urban Trading Company, 1907

Written at the dawn of cinema, an inspirational manifesto for film as an educative medium.

Geoffrey Macnab (Critic, UK)

A Life In Movies

By Michael Powell

The richness of Powell’s autobiography lies in its scope and its colour. On the one hand, it’s a fantastically useful resource for anyone interested in British film history. Powell offers vivid portraits of his colleagues and collaborators, many of them émigrés. This is a gossipy and very colourful memoir, full of anecdotes and asides about Powell’s romantic life and his sometimes vexed relationships with studio bosses. On the other hand, it is also a self-portrait by a brilliant and uncompromising English film-maker.

A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies

By Martin Scorsese and Michael Henry Wilson, Faber & Faber, 1997

Published to accompany a BFI documentary, this is a beautifully illustrated and very sharp-eyed tour through a century of American cinema by a true obsessive. Scorsese is as interested in Allan Dwan, Phil Karlson, Jacques Tourneur and Sam Fuller as he is in the bigger-name directors.

Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges: His Life in His Words

By Preston Sturges, Simon & Schuster, 1990

Sturges’ autobiography is as well written, droll and well observed as his best films.

The Magic Lantern

By Ingmar Bergman, translated by Joan Tate, Hamish Hamilton, 1987

There’s a wild streak of perversity to Bergman’s autobiography. He is honest and self-lacerating about his own foibles and equally caustic about those of others. Morbidity and lyricism run side by side as he lays bare his demons.

An Autobiography of British Cinema

By Brian McFarlane, Methuen, 1997

This book is easy to undervalue. At first glance it looks like a series of nostalgic, fireside chats with actors and film-makers from the good old days of British cinema. However, no one else was doing these interviews. Thirteen years on, many of the 180 interviewees have died. McFarlane did future British historians an extraordinary service by capturing their reminiscences.

Adrian Martin (Critic, Australia)

Theory of Film Practice

By Noël Burch, Secker & Warburg, 1973

A book that opens minds to formalism in the fullest and most supple way. Burch has changed his position many times since 1967 (when the chapters first appeared in Cahiers du cinéma), but there is still much to excite in these pages.

The Memory of Tiresias: Intertextuality and Film

By Mikhail Iampolski, University of California Press, 1998

So you think you know what intertextuality is? Iampolski, a pre-eminent contemporary Russian theorist, gives a dazzling demonstration of how, when, where and why films quote other films (and other media) and why we should care. A book so far ahead of its time we haven’t caught up with it.

The Material Ghost: Films and Their Medium

By Gilberto Perez

The long tradition of sensitive film aesthetics (it would once have been called film appreciation), from Béla Balázs to V.F. Perkins, finds its apotheosis in Perez’s superb book, as fully literary as it is analytical. Has anyone ever written this beautifully about Dovzhenko, Renoir or Straub-Huillet?

Deadline at Dawn: Film Criticism

1980-1990 By Judith Williamson, Marion Boyars, 1992

Journalist-critic heroes play out, on a weekly or even daily basis, the tension between the pressure to publish an instant response and the background resource of a lifetime’s reflection. Bazin, Daney, Rosenbaum and a dozen others fill this role admirably, but my vote is for Britain’s own Judith Williamson, whose books of collected reviews from the 1980s and ’90s are an unending inspiration.

Poetics of Cinema

By Raúl Ruiz, Dis Voir, 1995 (volume 1) and 2007 (volume 2)

Writings on film by film-makers form a generally undervalued genre. Among the many candidates – from Eisenstein, Tarkvosky and Pasolini to Alexander Kluge, Marcel Hanoun and Alexander Mackendrick – Ruiz’s ongoing Poetics of Cinema project stands out for its intellectual generosity, its luminous storytelling, its sly wit and its surrealist vision of what cinema could still become.

PLUS FIVE UNTRANSLATED GEMS:

Method

By Sergei Eisenstein, Museum of Cinema, Eisenstein-Centre, 2002

A casual observer might think we have much or most of Eisenstein’s writings in English, but the complete assemblage of his lifelong two-volume project Method has only appeared in Russian (and German) over the past decade. It will forever change the way we regard his life, work and thought. Fortunately, thanks to the gifted Russian-Australian scholar Julia Vassilieva, this project is on the way.

De la figure en général et du corps en particulier: L’invention figurative au cinéma

By Nicole Brenez, De Boeck, 1998

English-language film cultures have kept pace with French aesthetic philosophers like Jacques Rancière and Alain Badiou, but forgot to check where film analysis itself went in France after the heyday of semiotics. Here’s the answer: the most radical, innovative and inventive tome of cinema study in the past quarter-century, boldly proposing a ‘figural’ approach that combines meaning with emotion, history with imagination. Brenez is our greatest living critic.

Im/Off: Filmartikel

By Frieda Grafe and Enno Patalas, Hanser, 1974

Emerging from Filmkritik magazine in the late 1950s, this lively pair shaped much future German-language film culture to come with their analyses, programming, teaching and restoration work. Grafe (1934-2002), in particular, combined a crisp, evocative, Barthesian style with a rigorous eye and brilliant mind. This book is among the key chronicles of the 1960s and ’70s revolutions in cinema and film criticism.

Viv(r)e le cinéma

By Roger Tailleur

Francophiles, in general, know a lot about Cahiers du cinéma (and the whole artistic-intellectual culture that goes with it) and almost nothing about Positif (ditto). The saddest lacuna of all is Roger Tailleur (1927-85), an extraordinary prose stylist and encyclopaedic brain who, on a good day, makes Manny Farber seem like Harry Knowles. This selection, lovingly assembled by Positif comrades Michel Ciment and Louis Seguin, and containing classic essays on Bogart, Antonioni, Hawks and Marker, really just scratches the surface of Tailleur’s remarkable oeuvre – a true thinking-person’s cinephilia.

Kantuko Ozu Yasujiro

By Shigehiko Hasumi, Chikuma Shobo, 1983

Hasumi’s analytical method is deceptively simple: he takes us through the facts, limpidly described, of the everyday world of Ozu’s films – the walking, sitting, dressing, banal chit-chat – in order to arrive at often devastating revelations of this master director’s sensibility at work. Few critics give us such a concrete sense of what Godard once called “the evidence”. Cahiers du cinéma published a French version in 1998; we English readers are still waiting.

Peter Matthews (Academic, UK)

Agee on Film: Reviews and Comment

By James Agee

The greatest American film reviewer of the 1940s is a neglected figure these days, no doubt as his lofty humanist standards are out of tune with our own cynical resignation to ‘entertainment’. Ever the disappointed idealist, Agee offered grudging praise to such compromised efforts as Meet Me in St. Louis and Double Indemnity in long, delicately cadenced sentences that would never survive the copy editor now. Yet he was equally a master of the short demolition job (Princess O’Rourke: “An unobtrusive raising of the window, and the less said the better”), while his clairvoyant appreciation of Zéro de conduite almost single-handedly put Jean Vigo on the map in the English-speaking world. Though he could get it wrong (as in his cranky dismissal of Citizen Kane), Agee’s intense moral engagement with cinema sets him far above critics who merely get it right.

Katharine Hepburn: Star as Feminist

By Andrew Britton, Studio Vista, 1995

The competition isn’t fierce, but this book remains easily the best serious full-length study of a star. Shunning the high road of 1970s ‘apparatus theory’, with its curiously self-defeating notion that pleasure is an ideological error, Britton champions Hollywood icons as authentic sources of emotional and political inspiration. Hepburn’s fey, tomboyish persona may not have been radical exactly, but its very oddity created a worrying disturbance in her films that even the ritual clinch at the end didn’t entirely pacify. Stars back then embodied vital social contradictions – one doubts whether the featureless pretty people of contemporary celebrity would repay so subtle and scrupulous a treatment.

The Material Ghost: Films and their Medium

By Gilberto Perez

This volume has already become a milestone in film criticism, and it isn’t hard to see why. For one thing, Perez magnificently vindicates the beauty of illusionism – a salutary attitude after decades of academic militancy that judged it a ruling-class plot. But even more crucially, he understands how every general theory of cinema must start from its concrete particulars as an artform. The book is really about nothing beyond the author’s own infinite sensitivity to the implications of style. Has anyone else been quite so astute regarding the poetics of the shot/reverse shot (in Straub-Huillet’s History Lessons) or the uses of stasis (in Dovzhenko’s Earth)? A work of transcendent intelligence.

Notes on the Cinematographer

By Robert Bresson

These aphoristic memos from the legendary director are often as inscrutable as Zen Buddhist koans, yet reflecting on them can produce a similar enlightenment. Bresson’s notorious contempt for acting is explained here in the distinction he draws between cinematography (pure writing with images) and mere cinema (still beholden to the mimetic fakery of theatre). The professional player counterfeits truth vaingloriously, whereas the amateur or ‘model’ simply reveals a soul. Essential reading for anyone curious about the physics and metaphysics of film, this slender volume can be profitably revisited over a lifetime.

Sirk on Sirk: Interviews with Jon Halliday

Edited by Jon Halliday

A book that revolutionised film studies. Douglas Sirk’s erudite exchanges with Halliday in 1971 turned his previous reputation as a merchant of lachrymose piffle upside down by revealing he had been a cool ironist all along. Universal loved the Panglossian optimism of the title All That Heaven Allows, but Sirk knew what it really meant (‘heaven is stingy’) and proved the point with a mise en scène that systematically undercuts its own chocolate-box display of luxury. Through his sophisticated apologia for melodrama, a despised genre was propelled into the academic spotlight where it has remained ever since.

I could as easily have picked William Rothman’s Documentary Film Classics, Robin Wood’s Hitchcock’s Films Revisited, Stanley Cavell’s Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage or Paul Schrader’s Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer. I haven’t included André Bazin’s What is Cinema? because it sits in a class by itself.

Sophie Mayer (Academic, UK)

Decreation

By Anne Carson, Alfred A. Knopf, 2005

Beauty and the Beast: Diary of a Film

By Jean Cocteau

Essential Deren: Collected Writings on Film

By Maya Deren, edited by Bruce McPherson, Documentext, 2005

Queer Edward II (annotated screenplay)

By Derek Jarman, BFI, 1991

When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender and Cultural Politics

By Trinh T. Minh-ha, Routledge, 1991

Henry K. Miller (Academic, UK)

Let’s Go to the Pictures

By Iris Barry, Chatto & Windus, 1926

A product and record of the years when cinema first came to be ‘taken seriously’ in Britain, to use the conventional phrase. Barry was a cinephile pioneer among the literati, and one of film culture’s seminal figures. Very little was outside her scope. Sample observation: “Every habitual cinemagoer must have been struck at some time or another by the comparative slowness of perception and understanding of a person not accustomed to the pictures: the newcomer nearly always misses half of what occurs. To be a habitué makes one easily suggestible through the eye, quick at observing manners, gestures and tricks of expression.”

The Aesthetics and Psychology of the Cinema

By Jean Mitry, Indiana University Press, 1997

Overflowing with riches, it’s something of a scandal that Mitry’s summa went untranslated until the 1990s while the canon was packed by scores of philosophers manqués.

Films and Feelings

By Raymond Durgnat, Faber & Faber, 1967

Hard to pick just one Durgnat. Films and Feelings makes it because its extended chapter on the history of Franco-Anglo-American film criticism, ‘Auteurs and Dream Factories’, has yet to be bettered.

The Studio

By John Gregory Dunne, Farrer, Straus & Giroux, 1969

This account of a year at Twentieth Century Fox during the dying days of the dream factory is the best of the ‘inside Hollywood’ books by dint of Dunne’s peerlessly dry prose.

Cinema: A Critical Dictionary

Edited by Richard Roud, Secker & Warburg, 1980

The single best reference work on the cinema I’ve dipped into, this ought to have become standard household issue. Having assembled an all-star team of contributors – from Jean-Andre Fiéschi to Robin Wood to P. Adams Sitney – editor Roud (an S&S mainstay) himself jumps in at the end of each entry to register the extent of his disagreement.

Kim Newman (Critic, UK)

An Illustrated History of the Horror Film

By Carlos Clarens, Putnam, 1967

The first film book I ever bought – or nagged my parents to buy me – and still a model of genre history/criticism, teasing out bigger narratives from the mosaic achievements of individual films.

Kings of the Bs: Working Within the Hollywood System

Edited by Todd McCarthy and Charles Flynn, Dutton, 1975

Full of important things, like Manny Farber on Val Lewton and Roger Ebert on Russ Meyer, and evaluations of previously obscure films (Thunder Road) and film-makers (Sam Katzman).

Looking Away: Hollywood and Vietnam

By Julian Smith, Scribner, 1975

A study that manages to say a lot of fascinating, illuminating things about its subject even though it labours under the handicap that when it was published (1975) Hollywood had made almost no films about the Vietnam War.

Nightmare USA: The Untold Story of the Exploitation Independents

By Stephen Thrower, FAB Press, 2007

A huge study of independent American horror films of the 1970s and ’80s, this is a rare book that tells me things I didn’t already know. A monumental achievement, and it’s only the first part.

Science Fiction Movies

By Philip Strick, Octopus, 1976

Strick, a long-time S&S commentator, was one of the sharpest writers on science fiction in film and literature. This was one of a series of disposable illustrated books, but proved that the wordage between the stills needn’t just be rehashed press releases. Like all books I go back to, it has solid information, wide-ranging insight and an elegant, precise, wry prose style.

Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (Academic and writer, UK)

Qu’est-ce que le cinéma? (What is Cinema?)

By André Bazin, Editions du Cerf, 1958-62

Four little volumes of essays and reviews written in the 1940s and 1950s, published posthumously, that were absolutely formative for the film-makers of the nouvelle vague and for critics ever after. The selective and not very good English translation as What is Cinema? may have done more harm than good in reach-me-down film studies courses. A much better translation of most of the key essays has recently been published (What is Cinema?, edited and translated by Timothy Barnard, Montreal: Caboose, 2010), but for copyright reasons is available only in Canada.

Signs and Meaning in the Cinema

By Peter Wollen

A Bazin antidote. Harbinger of the theory boom of the 1970s, but much more readable than most of what followed.

Godard on Godard

By Jean-Luc Godard

Thoughts and opinions of the most important and revolutionary film-maker of the past 50 years. Beautifully edited and translated, but it unfortunately stops just before 1968. For Godard’s later thinking, avoid books and watch his extraordinary Histoire(s) du cinéma (1998).

For a reference book, am I allowed to put forward The Oxford History of World Cinema, despite being its editor (OUP, 1996)? If debarred, then the 2000 edition of the Time Out Film Guide, being less bulky than it has since become.

Michael O’Pray (Academic, UK)

Visionary Film

By P. Adams Sitney

Magisterial. It was written over 30 years ago, yet remains the most lucid and critically coherent account of American avant-garde film.

A World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film

By Stanley Cavell, Harvard University Press, 1971

The most sophisticated marriage of philosophy and film written. Brimming with ideas and beautifully written.

Stargazer: The Life, World and Films of Andy Warhol

By Stephen Koch, Marion Boyars, 1991

Still the best book on Warhol’s cinema. A cool gaze at a cool world.

My Last Breath

By Luis Buñuel

Surrealism, not as a set of dogmas, but as a life lived.

Durgnat on Film

By Raymond Durgnat, Faber & Faber, 1976

So sharp and so readable.

John Orr (Academic, UK)

My Last Breath

By Luis Buñuel

This is as sharp, witty and lacerating as all his best pictures; Buñuel’s observing eye turned into an act of reflective writing on his own life.

L’Imaginaire

By Jean-Paul Sartre (mistranslated as The Psychology of the Imagination), Gallimard, 1940

This is the book of books that helped me develop a cinematic eye.

Memoirs of the Beijing Film Academy

By Ni Zhen, National Publishers of Japan, 1995

Charts the rise of the Fifth Generation out of nowhere to astonish the world.

Ingmar Bergman

By Jacques Aumont, Cahiers du cinéma, 2003

In which the French critic says it all and shows us that further Bergman books must lie in new detail or a broader window on the film world.

Film Journal

By Eve Arnold, Bloomsbury, 2001

A masterpiece of stills photography that captures the world behind the movie camera, culminating in her extraordinary on-set pics of Marilyn and The Misfits.

Tim Robey (Critic, ‘Daily Telegraph’, UK)

The Aurum Film Encyclopedia

Edited by Phil Hardy, Aurum, 1983-98

This guide to the horror (1983 edition), science fiction (1984) and Western (1984) genres is addictive, exhaustive and unsurpassed.

Reeling

By Pauline Kael

My favourite Kael collection because the period it covers (1973-75) coincides with so many of her true passions.

Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism

By Jonathan Rosenbaum, University of California Press, 1995

No one else seems to get the point of film criticism as well as Rosenbaum, or to pursue it with such prickly independence.

Dirk Bogarde: The Authorised Biography

By John Coldstream, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004

This grasping of a unique career and life is an absolute model of diligence and wisdom.

The Devil’s Candy: The Bonfire of the Vanities Goes to Hollywood

By Julie Salamon, Delta, 1992

Outstrips even Steven Bach’s Final Cut as an appalled account of big-budget catastrophe.

Nick Roddick (Critic, UK)

André Bazin’s What is Cinema? introduced me to a different way of thinking about film and Christian Metz’s [two-volume] Essais sur la signification au cinéma (Klincksieck, 1968 and 1972) took things to a whole new level – even if the air up there was sometimes a little too thin to breathe.

In an entirely different context, a trio of Hollywood autobiographies – Sterling Hayden’s Wanderer (Alfred A. Knopf, 1963), Raoul Walsh’s Each Man in His Time: The Life Story of a Director (Farrer, Straus & Giroux, 1974) and Sam Fuller’s A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting and Filmmaking (Alfred A. Knopf, 2002) – confirmed that, even within the studio system, there were different lives being lived and different stories being told.

So, in a quite different but unforgettable way, did Kenneth Anger’s scurrilous Hollywood Babylon (J.J. Pauvert, 1959), which should be prescribed reading on every po-faced film course.

One that got away: Hugh Fordin’s MGM’s Greatest Musicals: The Arthur Freed Unit (Da Capo, 1996), which I lent to someone in 1976 and never saw again.

But if there is one book to rule them all, it is Peter Wollen’s Signs and Meaning in the Cinema. The revised and enlarged edition of 1972 is the most concise, lucid and inspiring introduction to thinking about film ever written.

Jonathan Romney (Critic, ‘Independent on Sunday’, UK)

Deadline at Dawn

By Judith Williamson

This is an exemplary collection, with a superb opening essay on the importance of resisting complicity with the culture supermarket. Its key statement, provocative but true: asking a critic what films to go to is as inappropriate as asking a geographer where to go on holiday.

Devant la recrudescence des vols de sac à main, cinéma, télévision, information

By Serge Daney, Aléas, 1997

This was my first exposure to the complexity, provocation and sometimes perversity of this French critic, a champion of cinephilic promiscuity and a brilliant expander of small, seemingly inconspicuous details into troubling symptoms. The title is what they used to warn audiences about in French cinemas: “Given the increase in handbag thefts…”

Flicker

By Theodore Roszak, Summit, 1991

Dan Brown avant la lettre for film buffs and those who tolerate their obsessions, Roszak’s novel is the best airport thriller ever, a passionate mythomanic celebration of cinema and its possible secret histories and, incidentally, a prescient forecast of the satanic-brat film-making generation of Gaspar Noé, Harmony Korine, Eli Roth et al. If ever I were to use the term ‘unputdownable’…

Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles

By David Thomson, Alfred A. Knopf, 1996

Biography as something close to picaresque fiction. At once imaginative myth-making and insightful, demystifying critical essay.

The Phantom Empire

By Geoffrey O’Brien, W.W. Norton & Company, 1993

A sui generis reimagining of film history – a poetic treatise, cultural delirium and phenomenological evocation of the mysterious, multiform rapture of watching. O’Brien’s prose textures alone bear testimony to the power of film to galvanise the creative impulse.

Jonathan Rosenbaum (Critic, USA)

Films and Feelings

By Raymond Durgnat

This first collection by the most thoughtful, penetrating, and far-reaching of UK film critics ever remains scandalously overlooked and undervalued. Conceivably more ideas per page can be found here than in the work of any other English-language critic, and Durgnat’s grounding in surrealism and the school of Positif is merely one of the starting points for an exploratory critical intelligence that is nonetheless quintessentially English.

Godard on Godard

By Jean-Luc Godard

I also prize the expanded original, Jean-Luc Godard par Jean-Luc Godard of 1985 – it’s only the first of two volumes, but still a doorstop at 638 pages. The shorter English version of this seminal collection of criticism and interviews may be only 292 pages, but Tom Milne’s translation and commentary are exemplary, and there’s no other volume of criticism from Cahiers du cinéma that has influenced me as deeply. (The main reason, incidentally, why I haven’t selected any collections in French by André Bazin or Serge Daney is the absence of any fully satisfying volume in the first case and too many possible candidates in the second.)

More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts

By James Naremore, University of California Press, 2008 (revised and expanded edition)

Although it’s hard to arrive at a single title by my favourite academic film critic (my second choice would probably be the updated edition of The Magic World of Orson Welles), this is probably the most enjoyable, edifying, and rereadable of Naremore’s books – and certainly the best study of noir ever published.

Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies

By Manny Farber

After much internal debate, I’ve opted for this essential collection over the far heftier Farber on Film because this includes the lengthy and indispensable interview Farber and Patricia Patterson gave to Richard Thompson in 1977, whereas the other volume, even though it sports the almost accurate subtitle The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber, contains only excerpts from it.

Romantic Comedy in Hollywood: From Lubitsch to Sturges

By James Harvey, Alfred A. Knopf, 1987

Sukhdev Sandhu (Critic, ‘Daily Telegraph’, UK)

Channel 4 Guide to François Truffaut

Channel 4, 1984

As all who recall the glory days of the fanzine will know, great, life-changing literature often comes through the front door in a self-addressed envelope. This small booklet, issued as a pedagogic aid of sorts, is a reminder of a time when terrestrial television scheduled whole series dedicated to individual arthouse directors (at prime time!) – series that would initiate ignorant schoolboys like me into the joys of world cinema.

Notes on the Cinematographer

By Robert Bresson

Geoff Dyer once wrote: “Spare me the drudgery of systematic examinations and give me the lightning flashes of those wild books in which there is no attempt to cover the ground thoroughly or reasonably.” Bresson’s slender collection of jottings and aphorisms (“The ejaculatory force of the eye”; “The terrible habit of theatre”; “Don’t run after poetry: it penetrates unaided through the joins”) is a witty example of the virtues of brevity.

100 Modern Soundtracks

By Philip Brophy, BFI, 2004

It doesn’t have the most compelling title, and this kind of synoptic volume is usually far less than the sum of its parts, but Brophy is a terrifically incisive and generative thinker about the possibilities of Ear Cinema, audio-delving into films as diverse as India Song and I Spit on Your Grave to create what he calls a “Braille for the deaf”.

The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era

By Thomas Schatz

As a film writer, my knee-jerk position is to use the word ‘studio’ as shorthand for greed, enervated groupthink, imaginative inertia, capitalism, western imperialism, evil itself. Sometimes, especially after you’ve just stumbled out of the remake of Clash of the Titans, that seems an intellectually responsible position. Mostly though, as this fastidiously researched and elegantly argued rebuff to auteurism shows, it’s not: the complex mesh of marketing, production and management enabled as much as it retarded the creation of the best US cinema of the mid-century.

An Amorous History of the Silver Screen: Shanghai Cinema, 1896-1937

By Zhang Zhen, University of Chicago Press, 2006

As the years trundle by, I’m more and more embarrassed by the parochialism of my filmic knowledge. Of Bollywood and Nollywood and Latin American cinema I know a bit, but not as much as I ought. As for Chinese film, well, this superb history, in which Zhang spotlights the teeming interplay between movies, photography and architecture in early 20th-century Shanghai, performs the function of all the best literature: it leaves you ravenous for more.

Jaspar Sharp (‘Midnight Eye’, UK)

The Japanese Film: Art and Industry

By Joseph L. Anderson and Donald Richie, Princeton University Press, 1959 (expanded edition 1982)

Although only covering developments prior to the 1960s, this is still the most essential publication out there on Japanese film.

The Imperial Screen: Japanese Film Culture in the Fifteen Years’ War, 1931-45

By Peter B. High, University of Wisconsin Press, 2003

An exhaustive and fascinating account of how the Japanese film industry was mobilised during the war years.

From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film

By Siegfried Kracauer

Its arguments as to how Germany’s national cinema portended the rise of Nazism might seem a bit oversimplified, but this book still provides a fascinating insight into the rise and fall of one of the world’s greatest film industries.

A Pictorial History of Horror Movies

By Denis Gifford, Hamlyn, 1973

I owe my obsession with cinema to being given a copy of this at the age of ten.

Mondo Macabro: Weird & Wonderful Cinema around the World

By Pete Tombs, St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998

The book that really opened my eyes to some of the more obscure corners of global film culture.

Iain Sinclair (Writer, UK)

Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies

By Manny Farber

Proving you don’t need to rehash the plot (it’s only there to secure financing). And for that essay ‘White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art’. And for the undeceived appreciation of Sam Fuller. Rescues, with painterly intelligence, a defunct form.

Joseph Losey: A Revenge on Life

By David Caute, Faber & Faber, 1994

Begins with the balance sheet: accountancy, documentation, polemic. The cultural connections of that period, from Brecht to Pinter, nicely fixed.

From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film

By Siegfried Kracauer

Knotty meat. A good place from which to steal.

Film at Wit’s End: Essays on American Independent Film-makers

By Stan Brakhage, Polygon, 1989

Generous evaluations of his peers by the inspirational film poet.

Nouvelle Vague, The First Decade

By Raymond Durgnat, Motion, 1963

Provocative, opinionated and a little crazy. I read this one until it fell apart, pre-viewing in my imagination films I had not yet seen and might never see. A fine example of literature as catalogue.

David Thompson (Critic/documentarian, UK)

A Discovery of Cinema

By Thorold Dickinson, OUP, 1971

A Biographical Dictionary of Film

By David Thomson

Reeling By Pauline Kael

Film as a Subversive Art By Amos Vogel

The Parade’s Gone By

By Kevin Brownlow

I would also add a complete set of Sight & Sound – no kidding!

David Thomson (Critic/author, USA)

A Life

By Elia Kazan

I don’t think this has been equalled as a record of a life in show business desperate to get into art.

Final Cut

By Steven Bach

The most candid and complete account of a film, and a famous disaster – which looks better every time you see it.

David O. Selznick’s Hollywood

By Ronald Haver, Bonanza, 1980

The most beautiful film book.

This is Orson Welles

By Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Endlessly fascinating, a book of record that is bursting to be a novel.

The Deer Park

By Norman Mailer, Putnam, 1955

Mailer had so many great insights about film and they start in this 1955 novel.

Kenneth Turan (Critic, ‘LA Times’, USA)

Picture

By Lillian Ross, Rinehart, 1952

A terrific piece of journalism and a landmark in the history of American non-fiction writing, this look at how John Huston made The Red Badge of Courage remains the ultimate Hollywood behind-the-scenes story.

The Pat Hobby Stories

By F. Scott Fitzgerald, Scribner, 1962

The great American novelist turned his attention to a Hollywood he knew well for this collection of short stories about a washed-up screenwriter, which retain their relevance and punch to this day.

The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968

By Andrew Sarris

For US critics of a certain age this is the most obvious choice, but there is no overestimating the impact its English-language exploration of auteur theory had on serious filmgoers and critics.

The Parade’s Gone By

By Kevin Brownlow

The book that almost single-handedly revived serious interest in the long-reviled world of silent film.

King Cohn: The Life and Times of Harry Cohn

By Bob Thomas, Putnam, 1967

A deliciously gossipy biography of Harry Cohn, the feared and reviled head of Columbia Pictures. As comedian Red Skelton said of the man’s well-attended funeral, “It proves what Harry always said: ‘Give the public what they want and they’ll come out for it.’”

Catherine Wheatley (Critic/Academic, UK)

Hollywood Babylon