Pi

USA 1997

Reviewed by Mark Sinker

Synopsis

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

Maximillian Cohen is obsessed with numbers, a human calculator seeking patterns in p and the stock market. Suffering from migraines, he injects painkillers and suffers hallucinations. One day he meets Lenny, a Hasidic Jew, who tries to befriend him, saying that the Kabbalah and the Torah are numerical codes sent from God. Max's former teacher Sol, who spent 40 years seeking similar patterns, tells him to take a break. Euclid, Max's computer, spits out some impossible stock predictions and a 216-digit number, then crashes.

Businesswoman Marcy Dawson wants a meeting, but Max evades her. A newspaper says the stock market has just collapsed; Euclid's predictions were correct after all. Max hunts for the 216-digit number in the trash, but it's gone. Lenny and Sol both mention a 216-digit number, but Sol warns Max off his obsessive search. Dawson offers Max a chip to improve Euclid. He hallucinates finding a brain on the subway steps. He finds a shell and looks at it with a microscope. The rebuilt Euclid crashes, again spitting out the number. Max accepts Dawson's offer of the chip, shaves his head, injects himself and collapses. When he wakes, he has the number. Sol tells him that computers become conscious of themselves just before they crash; this number is a sign of this. Dawson menaces Max for the number. Lenny rescues him, but only so the Hasidim can have the number. Max refuses. Sol dies, and Max realises he too had discovered the number. Max trashes Euclid, and, thinking he has a microchip in his head, drills a hole in his skull, destroying his skill at calculation.

Review

A computer-age update of Der Golem (1920) by way of Jorge Luis Borges, where technology is rendered lethal by an admixture of quasi-Kabbalistic symbols, p is a Hegelian occult thriller that never sheds its sense of its own cleverness (not entirely merited). For a film that's basically about a man chasing the secret of the universe regardless of the cost to sanity and humanity, and despite its teasing claims to knowledge from the frontiers of the knowable, it's often a bit timid.

Part of the problem is that the film-makers don't understand the maths they're using to sex up their plot. Certainly p when represented digitally never ends; it is a doorway to the infinite, if you like. But to real mathematicians, proofs of p 's infinitude are linked to proofs of its 'transcendentality', professional jargon for a very rigorous algebraic form of patternlessness. For many the allure of the various geometrical diagrams flashed before us in montage during the credits derives from their visually 'abstract' mystery rather than their concrete content. Max has a little mantra setting out his philosophy of cosmic patterning: it shows him to be either a rotten mathematician, ignorant of p 's proven properties, or else a lunatic, the kind that blitzes Harvard professors with 'disproofs' of Einstein in angry green ink. This latter option, Max as madman, is so overdetermined (he's forever shooting up and seeing things) it wrecks much chance of drama.

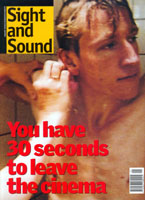

In its favour, p looks great, shot in a high-contrast black-and-white 16mm stock that recalls Maya Deren, Tetsuo, David Lynch and Cabaret Voltaire's early videos, with a nod to Buñuel that's a plain old bad pun (ants on a brain for bugs in a computer). Seeing the Hasidim in the role reserved by Hollywood for Native Americans - as repositories of ancient wisdoms that rationalists forget at our peril - is refreshing, if no less patronising.

As Max, Sean Gullette gives a one-note performance which sells short the sublimated passion of genuine intellectual obsession (compare recent television footage on Horizon of a choked-up Andrew Wiles recalling his solution of Fermat's 'last theorem'). The amused affection shown by female neighbours toward Max - Devi who feeds him, little Jenna who plays calculator games with him - makes up for the pushy corporate cipher that is Marcy Dawson. Max's mentor Sol has the best joke, about Archimedes and common sense - and perhaps the nicest touch is his apartment, which captures well the ambience of a Scientific American reader's room circa 1974, right down to the Go board instead of chess. But p would be much more fun if it wasn't trying to kid us that it's about so much more than fun.

Credits

- Producer

- Eric Watson

- Screenplay

- Darren Aronofsky

- Story

- Darren Aronofsky

- Sean Gullette

- Eric Watson

- Voice-over Written by

- Darren Aronofsky

- Sean Gullette

- Director of Photography

- Matthew Libatique

- Editor

- Oren Sarch

- Production Designer

- Matthew Maraffi

- Music

- Clint Mansell

- ©Protozoa Pictures, Inc

- Production Companies

- A Harvest Filmworks/Truth & Soul/Plantain Films presentation

- Executive Producer

- Randy Simon

- Co-executive Producers

- David Godbout

- Tyler Brodie

- Jonah S. Smith

- Co-producer

- Scott Vogel

- Consulting Producer

- Richard Lifschutz

- Associate Producer

- Scott Franklin

- Post-production Co-ordinator

- Katie King

- Assistant Directors

- Lora Zuckerman

- Henri Falconi

- Script Supervisor

- Kate King

- Casting

- Denise Fitzgerald

- Additional Cinematography

- Chris Bierlien

- Additional Camera Operator

- Nina Davenport

- Steadicam Operator

- Paul Burns

- Digital Film Recording

- Cineric Inc

- Special Effects

- Ariyela Wald-Cohain

- Computer Screen Graphics

- Jeremy Dawson

- Sneak Attack

- Can Schrecker

- Newspaper Graphics

- Gargan Sarch

- Khalsa Graphics

- Additional Graphics

- Sean Gullette

- Additional Editing

- Tatjana Kalinin

- Art Director

- Eileen Butler

- Snorri Cam Design

- The Snorri Brothers

- Vaccination Gun

- Sasha Noe

- Wardrobe

- Eric 'Shorty' Meyerson

- Make-up

- Ariyela Wald-Cohain

- Main Title Sequence

- Jeremy Dawson

- Sneak Attack

- Shofar Performed by

- Adam Burstein

- Music Supervisor

- Sioux Zimmerman

- Soundtrack

- "I Only Have Eyes for You" by Al Dubin, Harry Warren, performed by Stanely Herman; "Drippy" by Teddy Marks, performed by Banco De Gaia; "P.E.T.R.O.L." by Paul Hartnoll, Phill Hartnoll, performed by Orbital; "Kalpol Intro" by Sean Booth, Rob Brown, performed by Autrechre; "Full Moon Generator" by James Lumb, performed by Electric Skychurch; "A Low Frequency Inversion Field" by Jonah Sharp; "Some of These Days" by Shelton Brooks, performed by Joanne Gordon

- Sound Design

- Brian Emrich

- Sound Recording

- Ken Ishii

- Additional Sound Mixing/Recording

- Mark Enette

- Re-recording/Sound Mixer

- Dominick Tavella

- Pre-mixing Supervisor

- Joe O'Connell

- Medical Advisers

- Alissa Rosen

- Alan Lipp

- Judaica Advisers

- Richard Lifschutz

- Rabbi Alan Zelenetz

- Go Advisers

- Barbara Calhoun

- Michael Solomon

- Dan Wiener

- Microscope Cinematography Adviser

- Gerald McCollam

- Stunt Co-ordinator

- Marc Vivian

- Ant Wranglers

- Nico Tavernise

- Credits:

- Matt Dawson

- Cristina Hernandez

- Cast

- Sean Gullette

- Maximillian Cohen

- Mark Margolis

- Sol Robeson

- Ben Shenkman

- Lenny Meyer

- Pamela Hart

- Marcy Dawson

- Stephen Pearlman

- Rabbi Cohen

- Samia Shoaib

- Devi

- Ajay Naidu

- Farrouhk

- Kristin Mae-Anne Lao

- Jenna

- Espher Lao Nieves

- Jenna's mom

- Joanne Gordon

- Mrs Ovadia

- Lauren Fox

- Jenny Robeson

- Stanely Herman

- moustacheless man

- Clint Mansell

- photographer

- Totumminello

- Ephraim

- Henri Falconi

- Isaac Fried

- Ari Handel

- Oren Sarch

- Lloyd Schwartz

- Richard 'Izzi' Lifschutz

- David Strahlberg

- Kaballah scholars

- Peter Cheyenne

- Brad

- David Tawil

- Jake

- J.C. Islander

- man presenting suitcase

- Abraham Aronofsky

- man delivering suitcase

- Ray Seiden

- transit cop

- Scott Franklin

- voice of transit cop

- Chris Johnson

- limo driver

- Sal Monte

- King Neptune

- Certificate

- 15

- Distributor

- Guild Film Distribution

- 7,559 feet

- 83 minutes 59 seconds

- Black and White