Titanic Town

UK/Germany/France 1998

Reviewed by Geoffrey Macnab

Synopsis

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

Northern Ireland, 1972. Bernie McPhelimy and her family move to Anderstown, in Catholic West Belfast. Soon after they've arrived they see a running battle between an IRA gunman and the British army outside their house. Bernie's anger at the violence spilling into her backyard is exacerbated when a neighbour is dragged away by the soldiers and an acquaintance is killed by a stray bullet. After attending a meeting of local women to stop the violence, Bernie and her friend Deirdre decide to spearhead a new peace movement. Bernie provokes the wrath of the IRA with some ill-chosen words to the media. A brick is thrown through her window and her children suffer at school.

Bernie and Deirdre meet both the IRA leadership and the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. They propose a peace petition. At first, no one wants to sign. Bernie's actions drive a wedge between her and her family. Her husband falls ill, while her teenage daughter Annie starts a romance with a student who - she discovers much later - is an IRA volunteer. A mob led by Bernie's bigoted neighbour Patsy gathers outside the McPhelimys' house. In the clamour, Bernie's son receives a near-fatal head wound. Bernie and Deirdre's peace petition suddenly takes off and they gather 25,000 signatures, yet Bernie begins to fear the petition will make no difference. She and her family decide to leave Anderstown.

Review

Early on in Titanic Town we see a British soldier lying on his stomach in the flowerbed outside the McPhelimys' new house in Anderstown, West Belfast. It's an incongruous but telling image. He looks almost like a garden ornament, but his presence, like that of the IRA gunman a few minutes earlier, is taken as a personal affront by Bernie McPhelimy who refuses to accept the Troubles spilling into her own backyard. Repeatedly, quiet domesticity and political violence are juxtaposed: a dinner is interrupted by an explosion or a siren, a simple shopping trip or a visit to the hairdresser is blighted by a stray bullet.

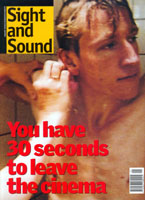

All Bernie wants is peace for her family. Julie Walters plays her as the archetypal housewife. Curlers in her hair, she is intent on keeping up appearances, always bustling and fussing. Confronted with slippery British politicians and plain-speaking IRA leaders, she reacts like an angry mother discussing a child's future with dim-witted and patronising teachers. It's an engaging but mannered performance, a little like Mother Courage done sitcom-style. Unlike Helen Mirren's character, who became politicised when she saw how the Long Kesh prisoners were treated in Terry George's Some Mother's Son, Bernie won't take sides. She scolds soldiers and terrorists alike.

Anne Devlin's screenplay doesn't hide the fact that many consider Bernie a naïve and meddlesome busybody. Even her husband is sceptical about her peace campaign. There is never any suggestion that Bernie's intervention is somehow going to sort out the Troubles once and for all, nor do the film-makers impose a pat, happy ending. The story, after all, is set in 1972. There are running gun battles when the McPhelimy family arrive in Anderstown and the tanks are rumbling along the streets when they leave.

Titanic Town is loosely based on an autobiographical novel by Mary Costello, whose mother was involved in the Peace Campaign of the early 70s. (The area is so named because of the Harland and Wollf shipyard which built the Titanic.) The film, however, is not simply about Bernie's fight against sectarianism. It also doubles up as a rites-of-passage yarn about her daughter Annie. Director Roger Michell (whose next film is the Four Weddings follow-up, Notting Hill ) handles the scenes between Annie and her schoolfriends and her burgeoning love affair with a medical student delicately enough. The problem is bringing the competing strands of the narrative together. At times it's as if there are two different films running side by side - one from the perspective of the mother and one from that of the daughter.

The mood oscillates wildly. When Bernie is holding forth to an interviewer on BBC Radio 4's Women's Hour or dropping clangers in television debates, the emphasis is on comedy. Then, an instant later, matters darken as somebody is killed or wounded. The film-makers can't resist caricature. The bigoted, loud-mouthed next-door neighbour Patsy and her malingering, thieving son are presented in an entirely negative light. Why they behave as they do is never addressed. The patronising, middle-class Protestant women are likewise used as comic targets. They're pelted with eggs, but such knockabout slapstick can't help but seem strained when, a few scenes later, Bernie's son is almost lynched by an angry mob. Unlike many films about the Troubles, Titanic Town isn't blighted by machismo and doesn't preach. It shifts the focus away from the politicians to the families whose lives are affected on a day-to-day level by the violence. Michell seems caught, though, in a no-man's land between gritty realism and upbeat, stylised comedy. For all its strengths, the film comes no closer to marrying its competing storytelling styles than Bernie herself does to bringing about peace.

Credits

- Producers

- George Faber

- Charles Pattinson

- Screenplay

- Anne Devlin

- Based on the novel by

- Mary Costello

- Director of Photography

- John Daly

- Editor

- Kate Evans

- Production Designer

- Pat Campbell

- Music

- Trevor Jones

- ©Titanic Town Limited.

- Production Companies

- BBC Films presents in association with Hollywood Partners/Pandora Cinema

- Supported by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland through its National Lottery Fund

- With the Participation of British Screen

- A Company Pictures production

- Developed with the assistance of British Screen Finance Limited

- Executive Producers

- David Thompson

- Robert Cooper

- Rainer Mockert

- Line Producer

- Sally French

- Production Co-ordinator

- Winnie Wishart

- 2nd Unit Production Manager

- Shellie Smith

- Location Managers

- Sam Breckman

- 2nd Unit:

- Victoria Misson

- Belfast Crew Locations

- Michael Casey

- Post-production Supervisor

- Maxine Stanley

- Assistant Directors

- Deborah Saban

- Olivia Lloyd

- Lee Trevor

- 2nd Unit:

- Matt Carver

- Script Supervisor

- Kim Armitage

- Casting

- Sarah Trevis

- Script Associate

- Robyn Slovo

- Script Consultant

- Anna Price

- Steadicam Operator

- Vince McGahon

- Special Effects Supervisor

- John Markwell

- Effects Technician

- John Dempsey

- Art Directors

- Dave Arrowsmith

- 2nd Unit:

- Antonia Birk

- Costume Designer

- Hazel Pethig

- Chief Make-up/Hair

- Jean Speak

- Titles

- Cine Image

- Music Producer

- Trevor Jones

- Music Co-ordinator for CMMP

- Victoria Seale

- Music Recordist/Mixer

- Gareth Cousins

- Musicians

- Guitars Arranger/Performer:

- Kipper

- Penny Whistle:

- Tony Hinnegan

- Soundtrack

- "Go Down Easy", "Back Down the River", "Easy Blues", "Over the Hill", "Solid Air", "May You Never" by/performed by John Martyn; "Rock 'N Roll Suicide" by/performed by David Bowie

- Sound Mixer

- Rosie Straker

- Dubbing Mixer

- Tim Alban

- Dialogue Editor

- Danny Hambrook

- Effects Editor

- Simon Gershon

- ADR

- Recordist:

- Glenn Calder

- Foley

- Artists:

- Ruth Sullivan

- Paula Boram

- Recordist:

- Jens Christensen

- Consultant

- Tess Costello

- Military Adviser

- Richard Smedley

- Stunt Co-ordinator

- Andy Bradford

- Armourer

- Bapty & Co.

- Cast

- Julie Walters

- Bernie McPhelimy

- Ciaran Hinds

- Aidan McPhelimy

- Ciaran McMenamin

- Dino/Owen

- Nuala O'Neill

- Annie McPhelimy

- Lorcan Cranitch

- Tony

- Oliver Ford Davies

- George Whittington

- Des McAleer

- Finbar

- James Loughran

- Thomas McPhelimy

- Barry Loughran

- Brendan McPhelimy

- Elizabeth Donaghy

- Sinead McPhelimy

- Aingeal Grehan

- Deirdre

- Jaz Pollock

- Patsy French

- Kelly Flynn

- Bridget

- Nicholas Woodeson

- Immonger

- Doreen Hepburn

- Nora

- Veronica Duffy

- Mary McCoy

- Cathy White

- Rosaleen

- Ruth McCabe

- Kathleen

- Caolan Byrne

- Niall French

- Cheryl O'Dwyer

- Maureen

- Maggie Shevlin

- Mrs Morris

- Timmy McCoy

- Colm

- Malcolm Rogers

- Uncle James

- Tracey Wilkinson

- Lucy

- Billy Clarke

- gunman

- Fo Cullen

- Miss Savage

- Simon Fullerton

- Jimmy Cane

- Duncan Marwick

- Lionel Thirston

- John Drummond

- sergeant

- Paul Trussell

- lanky para

- Lee Nettleingham

- Neil Maskell

- Peter Ferdinando

- Mark Mooney

- paras

- Darren Bancroft

- corporal

- Claire Murphy

- Nuala Curran

- Julia Dearden

- Mrs Gilroy

- Mairead Redmond

- Mairead Curran

- Andrew Havill

- officer

- Paula Hamilton

- Mrs Brennan

- Mike Dowling

- butcher

- Robert Calvert

- bus driver

- Jeananne Crowley

- Mrs Lockhart

- Peter Ballance

- Fergus

- Richard Clements

- Brian

- Colum Convey

- interviewer

- Amanda Hurwitz

- night nurse

- Tony Rohr

- Cork driver

- B.J. Hogg

- Chair

- Richard Smedley

- patrol leader

- Alan McKee

- reporter

- Tony Devlin

- Republican youth

- Andrew Downs

- ambulance driver

Breffni McKenna- paramedic

- John Quinn

- publican

- Packy Lee

- hijack youth

- Catriona Hinds

- TV journalist

- Christina Nelson

- Gerard Mccartney

- journalists

- Karen Staples

- nurse

- Kieran Ahern

- Father Clancy

- Brenda Winter

- Mrs Duffy

- Richard Orr

- man in black jacket

- Chris Parr

- 1st radio interviewee

- Certificate

- 15

- Distributor

- Alliance Releasing (UK)

- 9,140 feet

- 101 minutes 34 seconds

- Dolby

- In Colour