Gallery review

Dara Birnbaum: the caged artist

Arabesque

Laura Allsop on the video appropriator’s new and old visions of suffering for – and in – one’s art

South London Gallery, London, UK

9 December 2011–12 February 2012

In the mid-1970s, when New York artist Dara Birnbaum began working with video, Nielsen ratings revealed that Americans watched just over seven hours of TV a day. It was enough to convince the artist of the need to use, appropriate and deconstruct the language of TV in her practise. Over 30 years later, she is mining what’s arguably today’s dominant media – the Internet – for her latest work.

Birnbaum’s solo exhibition at the South London Gallery features a new four-channel installation entitled Arabesque, alongside single-channel videos and an installation dating from the 1970s. It seems odd to leave out her works from the intervening years, though in January 2012 the Gallery will present a one-off screening survey of her work from the late-1970s and 80s, including video Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978/9).

In the latter, probably her best-known work, Birnbaum showed Wonder Woman spinning around like a broken record, caught in the moment of becoming the bustier-and-knickers-clad heroine, the flow of images interrupted to give pause to question the nature of gender representation onscreen. Pride of place in this exhibition goes to the new installation Arabesque (2011), which unfolds over four screens the length of the ground-floor gallery and appears to deal with similar issues relating to the representation of women in culture.

The work takes its title from composer Robert Schumann’s 1839 Arabesque Opus 18, which he wrote for his wife Clara, and features YouTube footage across three screens of women and young girls performing the piece with varying degrees of proficiency. On a fourth screen to the far right is the only YouTube video the artist could find of someone (a woman) playing Clara Schumann’s Romanze 1, Opus 11, which she wrote for her husband. This latter footage is inter-cut with stills and written dialogue from the 1947 film Song of Love, a drama about the composer and his wife starring Katharine Hepburn and Paul Henreid. (Excerpts from Clara’s letters detailing her sadness, grief and love for her husband, who suffered from bouts of depression and madness, are also interspersed on one of the three screens of women playing Robert’s piece.)

Notwithstanding the dearth of people playing Clara’s highly accomplished Romanze 1 compared to the numbers playing her husband’s work, Arabesque does not impress itself as a work dealing solely with the side-lining of women from history. Rather it seems to foreground the notion of the Romantic artist, suffering and sacrificing for her art. The YouTube clips of women hammering away at the piano, some on stage in satin ball-gowns, others dressed down in their own music rooms, shows how prevalent is the notion of enslavement to one’s art – even if the art you perfect is not your own. Arabesque is an elegant, sometimes swooning work, with moments of humour and pathos. Though its use of social media continues Birnbaum’s early experiments with appropriation, it’s tonally very different to the other videos on display.

Attack Piece

Upstairs in a small room, you’re confronted with six single-channel, black-and-white videos dating from 1975, set up so that three TV screens mirror another three, with the videos playing simultaneously. In Addendum: Autism Birnbaum rocks back and forth on her heels, panting madly, her hair mussed and eyes wild. The sexual nature of her movements and sounds is juxtaposed with the frightened, confused look in her eyes, leading you to wonder if she is simulating being attacked.

Chaired Anxieties: Slewed meanwhile follows the artist’s tensed legs and arched feet as she rocks around on a fold-up chair. Her frantic movements, the way her hands grip the chair and the way she crosses and uncrosses her legs are all unnerving and suggestive of a struggle between self-consciousness and abandonment.

Another video, Mirroring, shows the artist obsessively moving towards and away from a mirror. These are powerful self-portraits, detailing the artist’s attempts to master self-representation, with the viewer caught between them and surrounded by numerous reflections and primal sounds.

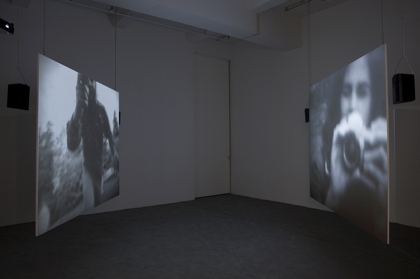

This sense of entrapment is further compounded on entering the two-screen installation Attack Piece (also 1975), in which footage projected onto one wall of the artist wielding a stills camera faces on the opposite wall a slide-show of images of camera-toting men running amok in her home. You again feel physically trapped between the different lenses.

The link between these older works and Arabesque comes courtesy of the 1976 video Everything’s Gonna Be Alright, which appropriates images and storytelling techniques from TV and magazines, interrupting them throughout with footage of a couple dancing to Bob Marley’s No Woman, No Cry, to discuss the hypocrisy of politicians and their attitudes to women. The images, music and sexual mores are certainly of their time – but the way Birnbaum shows pop culture acting as a salve for social ills seems just as relevant today.

See also

Sublime pants: Laura Allsop on Pipilotti Rist’s ‘Eyeball Massage’ exhibition (October 2011)

Electric dreamer: Laura Allsop on Nam June Paik, the first master of video art (January 2011)

Self Made reviewed by Mark Fisher (August 2011)