Border Control

Robert Rodriguez's latest south-of-the-border Western Once upon a Time in Mexico is set during a peasants' revolution and features corrupt generals and profiteering CIA agents. But while the film owes a stylistic debt to spaghetti Westerns, does it retain their radical edge, asks Edward Buscombe

In his book Spaghetti Westerns (1981) Christopher Frayling gives a handy checklist of what to expect in a Hollywood film set in Mexico: "the horses and armoured cars, the machetes and machine guns, the deserts and the barbed wire, the hacendados in their splendid charro costumes, the comic-opera generals, the fiestas, with guitars, fireworks and beautiful peasants dancing in the village square." Frayling points up the contrast between the colourful folksiness of Mexico as seen through American eyes and its location as the site of the first revolution of the 20th century, allying modern weaponry and military methods with the cunning and commitment of the peasants.

The source of the 'modern' in this confrontation in Hollywood terms is invariably Europe or America. Thus in The Wild Bunch (1969) General Mapache, fighting against the guerrillas, is aided by a Prussian army officer and the present of a machine gun and a motor car. In Bandido (1956) Robert Mitchum plays an American arms dealer, at first uncommitted but who gets progressively caught up in the revolutionary struggle. Mitchum is again the American outsider at the service of the revolution, this time an aviator with cutting-edge technology, in Villa Rides (1968). Two Mules for Sister Sara (1969) cast Clint Eastwood as an American whose skill with dynamite and other weapons is sorely needed by the Juaristas, an earlier generation of revolutionaries fighting the French. In The Mag-nificent Seven (1960) there's no revolution as such, but the seven mercenaries from north of the border bring tactical nous, technical skills and fire-power to assist the peasants fighting a predatory bandit.

Mapped on to the clash between the traditional and the modern is another: the opposition of emotion and intellect. It's as though the map of North America were anthropomorphised at the top is the head, seat of rational thought; below the belt are raging passions. Mexicans are headstrong, driven by elemental forces of love, hate and revenge. They laugh a lot, they sing a lot, they die a lot. By contrast the men from the north are in control, both of themselves and of the Mexicans they have come to help. They calculate the percentages and do their killing with efficiency.

In the Italian Westerns of the 1960s, Mexico became the preferred setting, partly for topographical reasons. The films were often shot in Spain, many around Almeria, whose desert landscapes offered a passable imitation of Mexico or the American southwest. But a Mexican setting supplied not just a generalised Latin aura congenial to the Italians. It also allowed the injection of a political agenda into the Western in a much more explicit form than a setting north of the border could plausibly permit.

Frayling explores the ways Hollywood's version of Mexico was developed and politicised in the more left-wing Italian films. Overlaid on the Marxism inherited from the Italian Communist Party was a concern for the struggles of the emerging third world, as theorised by Frantz Fanon in his 1961 book The Wretched of the Earth. A series of films by directors and writers such as Damiano Damiani, Sergio Sollima and Sergio Corbucci employed the same structuring opposition between an outsider (sometimes from Europe, sometimes from the US) and indigenous revolutionaries. But whereas in Hollywood's version there is rarely any discussion of politics (the revolution is just the good guys against the bad guys), in such films as A Bullet for the General (1966), Face to Face (1967) and A Professional Gun (1968) the outsider is confronted by the kind of social bandit who instinctively fights on behalf of the poor even if he does not yet have a fully developed political programme. There is thus a dialectic between the one who is distanced from the peasants' struggle, who is on the scene for motives of his own, usually mercenary, and the man of the people who, if not at the beginning, is by the end committed to their cause. Although the peasants can benefit from the technical assistance of the outsider, ultimately they must achieve victory by their own efforts: the philosophy of guerrilla leaders throughout the third world.

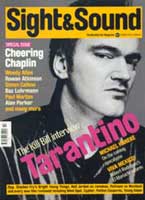

Superficially Robert Rodriguez's Once upon a Time in Mexico inhabits this world. Rodriguez occupies the status of a patron saint of American independent cinema, based on the legend of his first film El Mariachi (1993), which cost $7,000 of his own money to shoot and grossed $2 million. (Actually, as John Pierson points out in Spike, Mike, Slackers & Dykes, his informal history of the indie movement, Columbia spent another $1 million on the film before releasing it.) Visiting the set of Desperado (1995), Rodriguez's big-budget sequel to El Mariachi, Quentin Tarantino (something of an éminence grise: they worked together on 1995's Four Rooms and From Dusk till Dawn) at once recognised the influence of the Italian Western and allegedly remarked, "This is your Dollars trilogy." Once upon a Time in Mexico now completes the sequence.

A well-meaning but ineffectual Mexican president is being plotted against by a cool but callous local drug baron Barillo (Willem Dafoe), who is bankrolling a corrupt army general to carry out a coup. Sands (Johnny Depp) is a CIA agent who is trying to sabotage the plot, but for reasons of his own (he plans to make off with the money used to bribe the general). The hero El Mariachi (Antonio Banderas) is a guitar-playing romantic whose beautiful wife (Salma Hayek) has been killed by the general and who is bent on revenge. Others involved include an American gangster (Mickey Rourke) being forced to work for the Mexican drugs cartel and a former FBI man out to revenge a colleague who was tortured to death by the drugs baron.

This story of treachery, venality, revenge and opportunism, so typical of Hollywood films with a Mexican setting, is dressed out with a good deal of local colour of the type Frayling identifies. Motorbikes substitute for horses, but there are guitars and machine guns in plenty. Some of the action is set in the picturesque town of San Miguel de Allende, its pastel-coloured buildings bathed in the bright Mexican light; the peasants march against the army under the disguise of a parade during the Day of the Dead (which as Frayling points out formed a major motif in Sergei Eisenstein's abortive Hollywood venture Que Viva Mexico!).

However, in Rodriguez's film the contrast between cold-eyed northern efficiency and passionate revolutionary commitment is replaced by a combination of cynical venality and lust for revenge. Any political significance has been evacuated from man-from-the-north Sands, who stands not for modern efficiency but for old-fashioned greed. He's a CIA man but there's no implication of US government interference; he's working on his own account and his technological edge is nothing more than a clunky false arm he uses to hide the gun he's holding under the table. No one in the story actually believes in the political system, with the exception of the president himself. The characters in control who are manipulating the action, Barillo and Sands, though ostensibly on opposite sides are united in their single-minded pursuit of money. The good guys, El Mariachi and the ex-FBI man, are motivated solely by revenge.

So despite its revolutionary subject matter, Once upon a Time in Mexico is more interested in the stylistics of the spaghetti Western than in its ideology. In so far as it does borrow aspects of its world view, these derive more directly from the films of Sergio Leone, a debt Rodriguez makes no attempt to disguise. His title could hardly signal more clearly its antecedents. Leone's Once upon a Time in the West (1968) is the summation of his work in the Western and his next film Giù la testa (1971) had several alternative titles, one of which was Once upon a Time the Revolution. Leone liked this formulation so much he used it in his last film, gangster epic Once upon a Time in America (1983).

There are few political idealists in Leone's work, and the combination of greed and revenge usually suffices as the motivation for his plots. Only Giù la testa has a character with political commitment, in the form of Sean (James Coburn), an IRA man who in the course of the film loses his enthusiasm for the cause. (With his motorbike and his skill as a dynamiter, Sean is another European with modern technical expertise.)

Rodriguez's stylistic debt to Leone specifically and to the Italian Western generally can hardly be overstated. His film is essentially a collection of action sequences, fast paced and skilfully choreographed, shot and edited (Rodriguez is his own cameraman and editor); the frequent use of the zoom lens gives the film a curiously authentic 1960s feel. The music, also composed by Rodriguez, is a straight pastiche of Ennio Morricone. A Leone trademark is the long-drawn-out, elaborately staged showdown between two gunfighters, in which all attempt at realism is abandoned and the action slowed to a seemingly endless series of close-ups. Rodriguez too is willing to sacrifice narrative plausibility to baroque stylisation when at the end Sands has been blinded by his opponents. Undaunted, he dons black leather gloves and straps on a pair of six-guns for a final ritual confrontation.

Sands cannot see, so he recruits a young child to help him shoot. The involvement of children in macabre death scenes recalls Leone's Once upon a Time in the West, in which Frank (Henry Fonda) cold-bloodedly shoots little Timmy McBain and hangs Harmonica by the neck, standing him on the shoulders of his little brother, who knows what will happen when he weakens. It's a favourite Leone rhetorical strategy to make extreme contrasts to shock the audience out of its complacency. Rodriguez tries for a similar effect in a scene where Barillo is having piano lessons. An unguarded remark by his teacher leads Barillo to order his execution; his civilised exterior hides a murderous nature. Is there an echo here of the Civil War prison camp in Leone's The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) where an orchestra plays to drown out the sound of beatings?

Mention of children might also recall The Wild Bunch, which begins with children tormenting insects and climaxes with a child shooting one of the Bunch in the back. But Peckinpah's presentation of violence, though it may have upped the body count in the American Western, is more serious than Rodriguez's. In Once upon a Time in Mexico lots of people get killed, but there's no real pain. The violence, as in the bravura scene of a shoot-out in a church, is balletic, pretty in its way but without consequences (nor does the scene contain any of the Italian Western's anti-clericalism).

Rodriguez has fun with ingenious weaponry. Besides Sands' false arm, El Mariachi has a machine gun hidden in his guitar case. Later a guitar case is used as a flame-thrower and turned into a bomb to be pushed under an army truck. Such outré weaponry is common in the Italian Western. In Leone's For a Few Dollars More (1965) Colonel Mortimer, the bounty hunter played by Lee Van Cleef, has a small arsenal of weapons stowed on his horse, including a six-gun fitted with a rifle stock. In Corbucci's The Big Silence (1968) Jean-Louis Trintignant sports a Mauser automatic. In Damiani's A Bullet for the General the revolutionaries acquire an enormous machine gun, with devastating effects. In Corbucci's Django (1966) the hero keeps his machine gun in the coffin he drags around.

There's a curious absence of sex in Leone's films. Only in Once upon a Time in the West is there a female character of any status, and even there the main characters mostly have other things on their minds than Claudia Cardinale. In Once upon a Time in Mexico El Mariachi is ostensibly motivated by revenge against the general who murdered his pregnant wife. But Salma Hayek's role, sketched in flashbacks, is marginal. We have no sense of a relationship; she is simply an icon of beauty and goodness for whom the hero grieves in a self-regarding way, at the end posing against the sunset, holding his wife's locket while he strums his guitar.

The spaghetti Western by no means exhausts the range of Rodriguez's borrowings. Hayek with a knife strapped to her thigh has a touch of the Lara Crofts, Mickey Rourke fondling his pet chihuahua evokes Charles Gray cuddling his cat in Diamonds Are Forever (1971), and Barillo's attempt to change his appearance by swapping faces with another man through plastic surgery recalls Face/Off (1997), John Woo's thriller (Woo, of course, has long been a favourite of Tarantino). The one source from which Rodriguez doesn't borrow is the real Mexico, with its deep-seated economic inequalities and social injustices, its political struggles between a landless peasantry and a powerful entrenched oligarchy. You'd have to be a real independent to take on that.