Supertramp

Nearly one hundred years after his first screen appearance, Charles Chaplin's Little Tramp remains one of cinema's most cherished icons. But there's more to Chaplin than his battered bowler hat and mobile moustache.

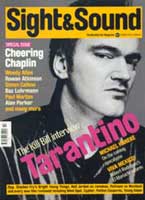

Few careers in film have reflected the challenges of their time quite like Chaplin's. A natural-born entertainer, he was also one of cinema's first auteurs, creating work that drew on his personal experiences to delight millions; a tireless perfectionist, he filmed take after take in pursuit of the most carefree comic effect; steeped in the hard-knocks traditions of London's 1890s music-hall scene, his films mixed Victorian sentiment with sharp contemporary views. He made movies that danced to the rhythm of modernity and captured the anxieties of changing political times. As a package of theatrical and DVD presentations of his work is issued in the UK, we asked film-makers, actors and critics, including Woody Allen, Baz Luhrmann and Rowan Atkinson, for their views on Chaplin. Their comments are featured as part of a 13 page special on Chaplin in the magazine. And here, comedian and writer Paul Merton gets back to basics and explains why Chaplin is so funny it hurts

Over the years it's become fashionable to denigrate Chaplin. "Keaton," they say. "Oh yes, Keaton is extraordinary. But Chaplin? He's just pathos." Yet Buster Keaton himself said that Chaplin was the greatest comedy director that ever lived, and Stan Laurel agreed with him. Groucho Marx called him "the funniest man on earth", and Groucho Marx hadn't a good word to say about anybody. Three years ago Evening Standard columnist A.N. Wilson went so far as to argue that Chaplin had never been funny, that no one had ever been amused by him. In response I wrote a stiff letter on a piece of cardboard which they completely failed to publish in which I suggested that not only had Charlie never been funny, but that Michael Owen had never scored a goal and the Beatles had never had a hit record.

There are a lot of reasons why Chaplin fell out of favour McCarthyism, bad publicity surrounding a trumped-up paternity suit in the 1940s, and also perhaps the natural pendulum swing away from the idolatry of the 1920s and 1930s. But I think there's a simpler explanation.

For many years the only place you could see a Chaplin movie was on television. My first memory of watching him was in a dodgy print of Easy Street, with my grandfather, who had watched his films as a child (my grandmother was born in Bermondsey, a few streets away from where Chaplin was brought up). I loved it. But for most people, watching terrible prints projected at the wrong speed on small television screens, with an inappropriate honky-tonk piano score, reduced the silent films to a bewildering succession of vaguely comprehensible actions involving big men in large fake beards being kicked up the arse in a monotonous fashion. Interestingly, in the 1960s Keaton's films good-quality prints with live-music accompaniment had been rediscovered on the arthouse circuit.

I think the DVDs which are now available, with cleaned-up images and newly recorded scores, go a long way to bringing these films back to life. But to appreciate the Chaplin phenomenon fully I would still go and watch his films on a large screen with a live audience. You have to see his eyes only then will you understand why he's kicking the fat man up the arse. In simple socio-political terms, he kicks the fat man up the arse because it's funny.

But Charlie is more than funny. Let me take you back to 1914. (I know some of you will have made other arrangements, but let's go back to 1914 anyway.) Chaplin has been a film star for just under a year, his superior acting and enormous charm quickly setting him apart from the frantic mugging and over-the-top histrionics of his fellow Keystone comics. He's funny, he's sexy and he's naughty. His early appeal rests with women and children. He flirts with the pretty ladies in the park while simultaneously kicking the fat man up the arse.

When he moves to Essanay Studios he has two weeks instead of two days to make a picture. One of these is The Tramp. It's set on a farm and much of it is tedious cartoon slapstick: a giant mallet smashed over a farmhand's head causes no more than a quick rolling of the eyes; pitchforks are tiresomely prodded into rustic bottoms. The violence is fake, and thus we feel no pain until when thwarting a robbery at the farm the Tramp is shot in the leg. Instead of jumping up and down in empty rage, he collapses. The wound is real. The pain is obvious. The Tramp is flesh and blood. He has dared, amid the cartoonery, to become real. And so, when he falls in love with Edna, the heroine who has nursed him back to health, then discovers she has a beau, we care. His misspelled note to her "I thort your kindness was love but it ain't cause I seen him. Goodbye" isn't intended to make us laugh.

This was Chaplin's first major artistic breakthrough. It is comedy of the soul. In the final scene Charlie shuffles away down the middle of a dusty track, hunched, dejected, lost. But then a tiny moment he kicks up his heels and straightens his back. There is now a cheery determination about him. Something will turn up tomorrow; the human spirit can't be crushed. We're with him all the way, and he achieves this with his back to the camera. We don't need to see the expression on his face. We know he's a human being.

This is one of the moments which Chaplin's detractors call pathos, as if a remarkable piece of sensitive acting is a weakness to be used against him. But for me it raises him above his contemporaries and sets new standards for the comedy film. After this breakthrough Chaplin was to use emotional reality in all his classic films. In The Immigrant it's his own experience of poverty and being an outsider; he starts making The Kid only days after losing his infant son. And in his often underrated masterpiece Limelight he uses his childhood the music halls, boarding houses and grinding poverty of Bermondsey ("Where we lived, next to the slaughter house and the pickle factory, after Mother came out of the asylum," as he describes it in his autobiography) and his own fall from grace to chart the decline of a major comedian. What happens when they don't laugh any more?

Charlie's own favourite among his films was The Gold Rush, which is packed with great scenes the dance of the bread rolls, eating the boot, Charlie as a chicken pursued by a hallucinating, hungry prospector. But if we judge the potency of a comedy scene by the number of laughs it generates, then the cabin balanced on the rim of the precipice is the funniest scene in the history of motion pictures. I took my wife Sarah to see the film at the Royal Festival Hall a couple of years ago. She couldn't believe a film could be so funny. For the seven minutes that the cabin teeters on the brink of the precipice, the audience couldn't stop laughing. And there's nothing that compares to being engulfed by waves of beautiful laughter.

In 1925 BBC Radio broadcast what was described as "An Interlude of Laughter: Ten Minutes with Charlie Chaplin and his Audience at the Tivoli". That's right: they broadcast an excerpt from a silent film. It was this very scene. And what did the listeners hear? According to the Star newspaper, they heard "whimsical crescendos of delirious delight, which culminated in torrential laughter that finally broke out into a terrific uproar a perfect storm of uncontrollable guffaws."

What more could you ask from another human being? Charlie gives you the lot. Riotous laughter, emotional depth, and the ever-present possibility that a fat man is about to be kicked up the arse.