Written On The Body

Set around the decaying canals of 1950s Scotland, Young Adam drifts on powerful undercurrents of sex and death. By Ryan Gilbey

"Young Adam is a movie just waiting to be made," declares John Pringle in his introduction to the most recent edition of Alexander Trocchi's 1954 novel, about Joe, an amoral drifter toiling on a barge between Glasgow and Edinburgh. Pringle goes on to worry about "how to create on film the narcissistic neurotic mess that is Joe's consciousness."

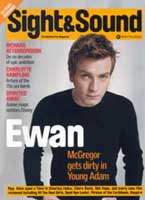

British film-maker David MacKenzie has made light work of the problem. He has cast Ewan McGregor, and apparently directed him not to do anything very much. "My mind was not blank," says Joe in the novel, "but I could not have been said to be thinking about anything." That admission could be the lynchpin of McGregor's performance. "I instinctively thought it was about a man's moral decline," said the actor while shooting the film, "but then realised that it's not. It's about a man who chooses not to involve himself in society's morals." His face, which we are so accustomed to seeing flare into life with romance or mischief, looks here as doomy as the river from which Joe and Les (Peter Mullan) drag a woman's corpse one slate-grey morning.

A person striving to interpret the film through Alexander Trocchi's life can take their pick from a shopping list of strange and sordid details. The Glaswegian author, who died in 1984 aged 59, was Scotland's own Beat icon. He earned the friendship and approbation of William Burroughs, Leonard Cohen and Terry Southern. He scratched out stark prose, often delivering one measly chapter at a time in exchange for enough cash to buy another armful of heroin before embarking on the next one. He founded and edited Merlin, the early-1950s avant-garde magazine that published Beckett, Genet and Ionesco. He was jailed for possession, and pimped his wife in Las Vegas to keep the smack coming. He wrote Cain's Book, a fictionalised junkie's memoir that is alternately staunch and sorrowful, while still in the grip of his own addiction.

And he spent time in Paris bashing out pornography. Among those efforts was an exploitative version of Young Adam in which formerly mortifying sex scenes were beefed up for cheap kicks. The version of the book Trocchi declared to be definitive didn't actually emerge until 1966, pretty much cleaned up but with the addition of an alarming food-and-sex scene that will earn the film its notoriety, if not a spin-off feature in a Sunday-supplement cookery column.

All this is undoubtedly significant. But the fact most pertinent to the experience of watching Young Adam is that Trocchi was a man who, in his poem 'A Beginning', felt no compunction about rhyming "sunlight" with "shite". David MacKenzie does something similar. His film is layered with off-colour visual and thematic rhymes, most obviously between sex and death, epitomised in the close-up of a fly traversing a woman's nipple, but also between sex and food, food and death, death and domesticity.

Finding the woman's corpse stimulates Joe and Les' prurience. Les can't be discouraged from recounting the story: you would think he was boasting about deflowering her. His wife Ella (Tilda Swinton) suspects as much. "You can't keep your eyes off a woman," she rebukes him, "even one that's dead." Holding court at the pub, Les reserves special enthusiasm for the dead woman's nakedness. When it's pointed out she was in fact wearing a petticoat, he shrugs off such details. But that petticoat, seen quivering in the breeze, symbolises the negligible barrier between the film's various opposing forces land and water, action and consequence, guilt and innocence. The petticoat, so inconsequential it dissolves in Les' memory, is all that divides this world from oblivion.

Joe is no less captivated by the body than Les. He actually seems more taken with it than with any of the women he paws solemnly in the course of the film. Of course, this is a man more emotionally attached to his roll-up or his morning egg than to his lovers. Even men figure more prominently in his affections. Examine the shot of Joe and Les scrubbing anthracite dust from one another's bodies and you'll find a mute tenderness absent from the ghastly sex scenes. Men don't do unpredictable things. They don't fall pregnant, or plummet into the Clyde. They don't let you down.

That might explain why Joe seems so comfortable with the corpse it is no longer able to impinge on his life, as it did when it was alive, when 'it' was 'she'. When asked how he thinks the body might have come to be in a state of undress, Joe develops an erotic fantasy about a woman shaking free of her garments. He hijacks the tragedy to titillate Ella, who is eavesdropping as she scalps a knobbly potato. MacKenzie is mindful not to dress up Joe's lust for Ella as anything fancy. In one scene he inserts a brutal cut from Ella painting Joe's ear with her tongue to an iron claw noisily dumping a stash of tangled metal on to a barge. If anyone is under the misapprehension that these loveless lovers will sail off into the sunset, that discordant editing should set them straight.

When Joe finally has Ella on the towpath while Les is playing darts, his post-coital conversation turns back to the corpse almost before their bodies have separated. Carnal pleasure brings death more keenly into focus for him, and vice versa. He's at his most stimulated when spooking his girlfriend Cathie (Emily Mortimer), who can't swim, by rocking the rowboat they are in; her fear of drowning excites him, and they make love there, out at sea (it must be a wholesome fuck, you find yourself presuming, because the camera has no interest in documenting it). Death, in turn, gets his gastronomic juices flowing. Trocchi writes that Joe's first thought upon laying out the woman's body is, "A hundred and thirty at elevenpence a pound." Her foot, trailing from the stretcher, is likened to a parsnip. Joe broods over "the dead woman and the egg and the salt", mixing up his gruesome discovery with a trivial grudge about breakfast portions.

Life and death are no less prone to confusion. MacKenzie has omitted the scene in which Joe and Les pass a tramp and idly debate whether or not he has expired, but the suspicion remains that the dead are mingling with the living. Grotesquely animated by the ebbing water, the corpse appears to be doing a kind of Mexican wave before it is pulled ashore. And it's another wicked touch that mere seconds after glimpsing the body we first meet Ella and her son both of whom look like they were also recently fished out of the river, with their lank greasy hair and sour-milk complexions. That Joe has unambitious designs on Ella only deepens the suggestion of necrophilia that hangs over the film: it's as though he wants to take this member of the living dead and screw her back to life. Initially their relationship carries suggestions of rebirth. "When he goes away," says Ella as she dispatches her son to boarding school, "it breaks my heart." Almost immediately she is offering Joe her breasts to suckle on, and she will watch as he swigs greedily from a jug of milk, the liquid pulsing down his chin.

Ella gets her Black Narcissus moment, bringing a splash of lipstick to a mouth, and a movie, hitherto starved of colour. But Joe has had his fill of her by then. Once Ella is properly alive, with demands and desires of her own, she becomes a liability to Joe, who prides himself on being free of moorings. It's a mirror image of his relationship with the deceased, who turns out to be a former lover. We see her making love with Joe only after we have become familiar with how she looks as a corpse. The flashback structure here, even more so than in Nicolas Roeg's Bad Timing, whips up the stench of crypto-necrophilia.

In the novel Trocchi places that word in the foreground during a bar-room discussion about the trial of the woman's suspected murderer. An unnamed drinker pipes up: "Necrophilia, it's called, but they won't let it out... You'll see!" The decision to exclude the word in the film exemplifies MacKenzie's tendency towards judicious pruning. The first meeting between Joe and Cathie spans five pages of the book. But the small amount of detail in this pared-down piece of writing can't help but seem fussy when compared to the movie, in which the seduction is shaved to the bone. "Would you like to come for a walk with me, Cathie?" "Where to?" "Over there." It's a masterclass in not-so-sweet nothings.

Only one adjustment, noticeable for being minor, feels needlessly cautious. Trocchi is careful to point out that while Joe plays no part in the woman's death, he does see her fall into the water. MacKenzie, on the other hand, denies him the role of witness: in the film, unlike the novel, Joe's back is turned at the moment of disaster, making him marginally less complicit. You can't help wondering what has been saved or redeemed here. Whatever, it should be a compliment to the film's otherwise scrupulous detachment that this alteration, which can easily be interpreted as a plea to audience sympathies, sticks out like a sore thumb.

The power of Young Adam lies in that detachment, which is even more radical in the film, where Joe is no longer the potentially unreliable narrator that he is on the page; now there is only one version of events, and it's horrible. Joe's accounts of his sexual escapades in the novel are more bored than boastful, but MacKenzie makes them pitiful: for instance, he shifts the sex scene between Joe and Ella's sister Gwen from the book's location (a field) to the comically drab setting of an alleyway soundtracked by distant footfalls. The picture goes further than the book in calibrating our responses to the sustained note of detachment, whether it's shock at Joe's remorselessness, or relief that the physical menace posed by the cuckolded Les fails to materialise, or laughter at the businesslike procession of Joe's sexual partners, none of whom puts up enough resistance to qualify as a conquest.

The film's numbness is so pervasive that we may not notice there is anything at stake until Joe tries to intervene in the workings of an external morality. If we experience fully the futility of his attempt to halt the death of an innocent man, who has been convicted for a murder that didn't even take place, then that can be attributed largely to MacKenzie's grasp of film language. A simple shift of focus in the closing shot transforms Joe's face from a vivid mask of despair into a shapeless blur. The act of not showing, in a medium built on illumination, would always be the nearest equivalent to the kind of literary understatement practised by Trocchi in Young Adam. That this gesture of concealment comes in a film which has balked at nothing indicates that some things are more shocking than sex and death.

Perhaps it is MacKenzie's confidence too that keeps us from noticing the commonplace nature of Joe's neurosis. In the book he glimpses in daylight the location of the previous night's liaison with Ella: "About 20 yards behind the hoarding was a cottage of whose presence we had been unaware the previous night. We had made love almost in its garden." Joe's concern appears to be that if he gets within a few feet of a privet hedge or an ornamental gnome he will be contaminated, and could wake up to find himself married with children. MacKenzie's achievement with this difficult film seems even greater when you realise he has conjured a plausible nightmare from what is essentially your everyday tale of one man's fear of commitment.