Eager Beaver

Veteran actor and director Richard Attenborough has often been described as a one-man British film industry. He is tied to an image of public works delivered with effusive theatricality, yet he denies membership of the great and the good. He talks to Geoffrey Macnab about a life of boundless energy

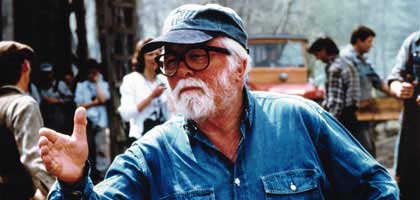

When you visit Lord Attenborough at his home Beaver Lodge, a picturesque Queen Anne house beside Richmond Green, you cross the courtyard, past his huge, shiny Rolls Royce, and are led through a walled garden to his private cinema, where he conducts interviews. Meetings have to be scheduled well in advance. Attenborough, 80 in August, remains as busy as ever. He's juggling film offers, striving to raise finance for his long-gestating Tom Paine project and pushing forward with plans to build the new Dragon International Studios in south-west Wales.

On the morning I speak to him he's much preoccupied with the news that his beloved Chelsea FC has been bought by a Russian tycoon. He confides that he gave away all his shares to club chairman Ken Bates on condition he improved facilities for the disabled. The next moment he's discussing his recent trip to Westminster to offer evidence to Gerald Kaufman's DCMS select committee on the state of the British film industry. "You're a British film industry all in yourself," Kaufman told him.

It was an apt remark. In various guises Attenborough has been at the heart of British film for more than half a century. Ask him if, after his many visits to Downing Street to lobby different governments, he's ever downcast at the way politicians treat British cinema, or if he's discouraged by the British film industry's habit of repeating mistakes from generation to generation, or wearied by the Herculean struggles he's faced to get his own movies made, and he gives a typically ebullient answer. "I'm very rarely depressed. I'm the most idiotic optimist. I get up in the morning and I'm absolutely certain it's going to be a great day. If I had not been, I wouldn't have made Gandhi. It took 22 years of labour and playing in bloody awful pictures to raise enough money to get a writer on board or to go to New Delhi to meet all the people concerned."

Attenborough is a protean and vaguely contradictory figure: an actor versatile enough to play murderer John Christie in 10 Rillington Place (1970) or Santa Claus in Miracle on 34th Street (1994), a film-maker capable of helming elaborate war epics (A Bridge Too Far, 1977) as well as intimate chamber pieces (Shadowlands, 1993), a dissenter who also seems to nestle comfortably within the heart of the establishment. He's a lifelong socialist (he joined the Labour Party in the mid 1940s and is still a member) who once made a movie extolling Churchill. He cites Edward G. Robinson (whom he met when he was in Flying Training Command in the early 1940s) as his most important screen-acting mentor and yet was equally close to Nol Coward (who cast him in In Which We Serve, 1942) and to the British theatrical tradition epitomised by Laurence Olivier (who once invited him to run the National Film Theatre). He describes himself as a character actor and sounds vaguely embarrassed when talking about his time as a matinee idol. At its peak, his fan club had 15,000 members; he closed it down on the grounds it had grown too time-consuming. ("I'd like to say it was all beneath me, but it wouldn't be true. It was assumed then that if you wanted to go on working in the cinema, you had to go on working on your public image and pay attention to box office," he muses, recalling the days when he used to open garden f tes and when even relatively minor British movie stars provoked Beatles-style hysteria among their fans. "They were strange times... an awful lot of crap was made.")

True to his public image, Attenborough is avuncular and charming, touches you on the hand, regales you with theatrical anecdotes, apologising profusely if you've heard them before. Yet his steeliness is always evident. One surefire way to irritate him is to ask if he regards himself as one of 'the great and the good'. "That's bollocks, actually," he protests, pointing out that much of his work, from his directorial debut Oh! What a Lovely War (1969) to Cry Freedom in 1987, has been done precisely to "knock the establishment". "I suppose I'm part of the establishment in the sense that I was chairman of the bfi for 12 years, chairman of RADA for 30, president of the National Film School since I set it up with Jenny Lee," he concedes, "but if it means I have to be involved politically with the establishment to achieve what I want to achieve, I don't have any embarrassment."

Richard Samuel Attenborough was born on 29 August 1923. His father Frederick (whom he refers to as "the guv'nor") was a don at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, who later became principal of Leicester University College. His mother Mary was one of the founder members of the Marriage Guidance Council. Both were politically active. During the Spanish Civil War his mother protested in public against Franco and "took under her wing" 50 Basque children. In the summer of 1939 the family adopted two Jewish refugees from the Kindertransport, Irene and Helge, who stayed for seven years.

"It was an extraordinary background my brother Dave and I had," Attenborough recalls. "My parents believed in the responsibility of one human being for another and in the idea that you had little right to experience the phenomenal joys of life unless you were aware of others who could be three feet or 3,000 miles away, facing difficulties you had no understanding of. They believed in the principle of putting something back. That, for them, was what life was about. And boy, they lived their life to the full." The subjects Attenborough was later to tackle as a director invariably reflected these social and political concerns. As he puts it now: "I want cinema to contribute something to argument, to thought, to antagonism, to anger, whatever, but always related to human affairs and human decency... I would be very sad if cinema were to deteriorate to such an extent that such films were not viable."

Perhaps inevitably, Frederick regarded his son's desire to go on stage as frivolous. "My father disapproved of acting as a career," Attenborough remembers, "but the real point was that I was academically second rate. I didn't enjoy school other than English and history. Science bored the arse off me." Frederick Attenborough wasn't puritanical he loved art and music hall and took his son on trips to the National Gallery to view newly acquired Seurat paintings and to a London cinema to see Chaplin's The Gold Rush (a key formative experience). Both parents also had a strong interest in theatre, but they considered it a precarious profession, an impression their meetings with various Rep actors working for Donald Wolfit's company, then in residence in Leicester, reinforced. Eventually father and son struck a bargain. In the unlikely event that Attenborough won a scholarship to RADA which would enable him to pay his fees, the family would support his attempts to become an actor. If he failed, he was to abandon his dreams.

Looking back on his acting career, Attenborough remains strangely ambivalent about the two roles that made his name: the young stoker in In Which We Serve and the adolescent gangster Pinkie in Brighton Rock (a part he played both on stage in 1943 and in the Boulting brothers' 1947 film). These roles, he suggests, led to him being typecast as the spiv or the "coward below decks", though what leaps out today is his febrile energy, a nervous quality that barely masks an underlying vulnerability.

Nicknamed by critics "the young Scarface", Pinkie is everything the high-minded actor playing him was not: venal, sadistic, immature. It was Attenborough's idea to signal the character's neurotic, scheming side by having him forever playing cat's cradle. He credits the Boultings with toning down the overly histrionic performance he had given on stage and with teaching him how to play to the camera rather than to "the top tier of the theatre". They sent him to Brighton to spend time with the real-life razor gangs who hung around the local racecourse. The young delinquents (one or two of whom appear in the movie) took him into pubs and betting shops and familiarised him with their rituals. What did they think of him? "Oh, probably that I was some poofy actor from London," he suggests cheerfully.

An impressed Graham Greene inscribed his copy of the novel "For My Perfect Pinkie", but Attenborough claims to cherish the Daily Express review even more. "Their critic Leonard Mosely wrote that my performance as Pinkie was as close to the character in the book as Donald Duck was to Greta Garbo. That's the only review I've always kept."

From Edward G. Robinson Attenborough learned that "you have to sort out the character long before you come on set" and that the camera will immediately pick up anything false or tentative about a performance. So when he played Christie in 10 Rillington Place he met the police officers who had worked on the case, interviewed Christie's acquaintances and even scrutinised his waxwork effigy at Madame Tussauds. His revulsion at Christie is self-evident. He took the role primarily because of his opposition to capital punishment. The challenge (vaguely akin to that of playing Pinkie) was to "find the nuances in the character" and not just play him as a homicidal monster.

Attenborough admits that for much of his acting career his primary motivation was "paying the gas bill". Even so, it's surprising someone as restless and perfectionist would saddle himself with a long run in a play like Agatha Christie's The Mouse Trap (in which he appeared alongside his wife Sheila Sym for two years) or accept parts in so many mediocre pictures. He continued to work with the Boultings in films like The Guinea Pig (1948) and I'm All Right Jack (1959). In the climate of the 1950s, he suggests, it was understandable that the brothers were no longer making movies as ambitious as Brighton Rock. "They were always political. John fought in the Spanish Civil War. But they had a marvellous sense of humour. And I think what they wanted to say they found almost impossible to mount commercially in straight dramas, whereas in satirical comedies they could raise the finance."

In talking about 1950s British film culture Attenborough paints a picture of an industry beginning to stagnate. "I was bored stiff with much of the acting I was doing," he recalls. In summer 1958, when he was stuck in the Libyan desert filming Sea of Sand and feeling especially frustrated, he and his close friend, the writer Bryan Forbes (or "Forbsey", as Attenborough calls him), decided, almost on a whim, to form their own production company. The name, Beaver Films, was the invention of their wives. ("They said, 'Why don't you call it Beaver? You two work like beavers.' Then we were both wearing beaver beards at the time.") The company's first film The Angry Silence (1959) bucked conventional financing trends in that the director, main actors, composer and even the film's solicitors were paid nothing up front. Kenneth More was supposed to play the lead, a lathe operator victimised for not taking part in a wildcat strike, but at the last minute he pulled out ("Kenny rang up and said, 'I've got someone to pay me real money'") and Attenborough reluctantly took over.

Attenborough and Forbes were part of Allied Film Makers (AFM), a production and distribution outfit formed in 1959 and backed by the Rank Organisation, but even as he rapidly established himself as a top producer on such films as Whistle Down the Wind (1961) and The L-Shaped Room (1962) Attenborough claims he had "no burning urge to direct". That changed in the early 1960s when Mothilal Kothari, a civil servant working with the Indian high commission, tried to interest him in making a film based on Louis Fischer's biography of the great Indian leader Gandhi. Attenborough read the book while on holiday and promptly telephoned Kothari from a call box. "Gandhi summarised everything I cared about and was interested in. I remember ringing Mr Kothari and telling him, 'I would love to make your movie. I think you're mad but I promise you here and now that I will devote the rest of my energy while I live to try to direct this movie if you will let me have it.'"

The hitch was that Kothari had no money. Attenborough's 20-year battle to get Gandhi financed has been exhaustively chronicled elsewhere (for instance in Goldcrest boss Jake Eberts' memoir My Indecision Is Final). Suffice to say that most of his other films were equally tough to put into production. "In a way it's my own fault," he suggests. "There's plenty of employment there if I wanted to make science-fiction movies or I didn't object to the pornography of violence."

Not that Attenborough is anything other than pragmatic. He raised the finance for Oh! What a Lovely War by claiming (falsely) to Paramount boss Charles Bludhorn that he had already enlisted Laurence Olivier, John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson and countless other British actors. Bludhorn told him, "Get five of those names and you can have the money." Thankfully, Olivier bailed him out. "He agreed to do it for equity rate. When I was leaving, he called down the stairs and said, 'Dickie, tell Ralph and Johnny I'll do it for equity minimum. Then those buggers will have to do the same.'"

Once he had begun directing Attenborough quickly decided he would "move heaven and earth to remain my own boss." This feeling was reinforced by his differences of opinion with Carl Foreman on Young Winston (1971). "I liked him very much. But the fact remains that he was the producer and writer and I was an employed director."

Attenborough is now among the few directors (alongside his friend Steven Spielberg) usually allowed final cut on his own movies, but he remains surprisingly self-deprecating about his work. "I'm not an auteur in any sense whatsoever," he says. "My great contribution is directing actors. I really believe I can do that as well as any other director I know of. But my films aren't the work of one artist whose imprint is there on screen for everyone to see." He cites Shadowlands as the film he's "least embarrassed by" and emphasises again and again the primacy of the writer. "The screenplay for Shadowlands came from one pen Bill Nicholson's whereas In Love and War had five writers."

Attenborough's fear now is that his brand of cinema humanistic, crusading, naturalistic is falling out of fashion. He may be regarded as a national treasure, but that doesn't mean it's any easier for him to get his films made. After two failures In Love and War (1996) and Grey Owl (1998) he's not "flavour of the month" in Hollywood. Nor are the British rallying around. In 1994, just after Shadowlands was released, he told the Sunday Express that the last five films he'd made, "including Chaplin, Cry Freedom, A Chorus Line and A Bridge Too Far didn't have one penny of British investment between them," an astonishing statistic given his pre-eminence as a British film-maker.

Nobody seems keen to get behind the Tom Paine project either. "The financiers aren't interested in the subjects I want to make," he states. "Trevor Griffiths' script for Tom Paine is one of the best I've read but it needs $65 or 75 million. It's period, it's religion, it's politics, it's morality. They ignore the fact that there are some wonderful, evocative man-to-man battles involved. There's Washington, Robespierre, Danton and two great love affairs."

The more he talks about the project the more fired up he becomes and the more you suspect he'll get Tom Paine into production somehow or other. After all, the financiers were every bit as sceptical about Gandhi. He didn't get discouraged then and he's not about to surrender now.