Primary navigation

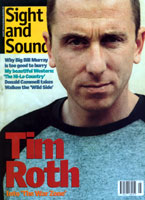

When Tim Roth turned director, no one expected a tough film about incest. Shane Danielsen talks to Roth about hurt

An elegant, unsparing adaptation of Alexander Stuart's novel, Tim Roth's directorial debut The War Zone depicts a teenage boy's discovery of an incestuous relationship between his father (Ray Winstone) and his older sister Jessie (newcomer Lara Belmont) - an event that irrevocably sunders his family even as it awakens his own sexual identity. The novel is by turns lyrical, shocking and surreal. Narrated by 15-year-old Tom (played here by Freddie Cunliffe), it describes extraordinary horror in a tone of peculiarly adolescent bewilderment, amplifying a typical teenage sense of estrangement from one's family into the realms of nightmare. Dismayed by his parents' decision to relocate to rural Devon, Tom retreats into silence, becoming an observer of rather than a participant in his family's daily life. And from this vantage he begins to notice things, to piece together the secret his father and sister are concealing. He confronts Jessie with his discovery; she denies nothing. Instead she takes him to London to meet a woman who is obviously her lover, and to whom, in a bizarre ménage à trois, Tom loses his virginity. Thus "blooded" he returns to the family home and confronts his father, with inevitably tragic results.

Yet despite the almost classical structure, ambiguities remain. Is Jessie victim, seductress or collaborator? Is Tom motivated by a desire to restore the familial status quo or to smash it beyond recognition? Is he acting out of disgust or inchoate jealousy, a petulant response to his own nascent sexuality? "It's all that," claims Roth. "All that and more. Abused children are complicit because they're made to be complicit; they keep the secret. That complexity is one of the things that attracted me to the story in the first place."

Put simply, Roth's intention here is to marry the grubby physicality of British realism to the more austere (if picturesque) tenets of the European art-house film - an aesthetic of leisurely takes, careful compositions and deliberate editing. It's a decidedly reverent approach, presumably intended to deflect accusations of sensationalism or prurience, and certainly there's nothing exploitative here - even at its most horrific the film maintains a tone of studied impassivity. Yet Roth's desire for respectability occasionally leads him astray: Simon Boswell's score, for instance, is too lush, too much at odds with the squalor of the events the film depicts. It's typical of the style of film-making to which Roth aspires - and which finds its visual covalent in the dark lustre of Seamus McGarvey's cinematography - but it also marks a definitive rupture between the British and European aesthetics he's attempting to reconcile.

In spirit The War Zone recalls Andrew Birkin's The Cement Garden (1993), taken from Ian McEwan's novel of the same name. Here we see a similar hothouse sexuality and ambiguous relationship between brother and sister. Both McEwan and Stuart (who adapted his own work for the screenplay) share a taste for the aberrant and unfathomable, for the irruption of deviant behaviour into the fabric of everyday life. And both evince a certain scepticism about the cosy integrity of the family unit.

From all accounts this project had been around for some time, but no one seemed willing to touch it. Though critically acclaimed at the time of its publication, the novel had garnered something of a dicey reputation, partly as a result of the controversy surrounding its exclusion from the 1989 Whitbread Prize after one of the judges allegedly threatened to resign if Stuart was named the winner. What has changed? Either there's been a shift in social awareness or an urgent desire to revoke taboos, depending on your point of view. But certainly after long decades of silence - or glossy treatment as in Louis Malle's Le Souffle au coeur and Bertolucci's La luna - incest and paedophilia have emerged as a dominant narrative strand in contemporary art-house cinema. From worthy-minded dramas (Aline Issermann's L'Ombre du doute, Claude Miller's La Classe de neige) to jaundiced films maudits (Happiness, Seul contre tous), filmgoers have been treated to increasingly regular instalments of the cinema of abuse.

One could argue that The War Zone goes further than any of its predecessors - if only by virtue of a single scene. Intriguingly, the incestuous act here takes place not in the house but in a disused concrete bunker, a remnant of wartime activity along the English coast. Situated on a high cliff, at the edge of a desolate landscape, the bunker functions as an exclusionary zone - a space outside the limits of the family home, the location that otherwise dominates. While faithful to the novel, this device proves faintly problematic. What does it say that the film's central crisis exists within a secondary narrative space? That here, and here alone, the dictates of conventional morality cease to apply? That the family home is to be read as a de-sexualised environment (unlikely given the presence of Tom's heavily pregnant mother played by Tilda Swinton)?

Yet the distinction exists. Tom's first realisation that something is amiss occurs when, arriving home to find the door locked from within, he peers inside a window of the house and remains transfixed by what he sees. But crucially the information is withheld from the viewer: there's no cut to his point of view, only the shifting index (appalled but also fascinated) of his expression. Later we see much more. We're taken inside the bunker, to watch the film's toughest sequence, in which a father sodomises his daughter. The camera keeps its distance - there's no unnecessary movement, no superfluous editing; the gaze is unflinching. By choosing not to depict the transgressive act taking place within the confines of a domestic milieu - by aligning it instead with this other, sexually charged space - Roth and Stuart make the bunker simultaneously a site of evil and a symbolic bastion of male sexual appetite. Something to be abhorred, but also contested and attained. And sure enough, by the film's end Tom will inhabit this space himself, his passage from adolescence to adulthood complete - a transformation that only adds to the ambiguity of the final scene in which brother and sister are together inside the bunker, their life outside, in the real world, in ruins.

The family home too is shot as a kind of fortress, isolated in a hostile landscape. Inside, life seems weirdly stalled - the rooms are in near-darkness; the silence is oppressive. The only contact with the outside world - the life they've left behind - is the telephone, upon which the father is constantly, almost furtively speaking, his back turned to his family. It's an appropriate image since this is a profoundly alienated film - more concerned with the distances between people than with their groping attempts at intimacy. And the world as it exists outside this unfortunate family is apprehended only fleetingly: a brief visit to London, an evening spent on the cliffs, a night-time drive to hospital. Mostly it's mediated through that seemingly endless string of telephone calls, that low voice, murmuring.

A comparison with Gaspar Noé's Seul contre tous proves instructive. Noé, for all his undoubted desire to shock, is careful to situate his story within a broader political context. His protagonist serves as a literal personification of social malaise, a blind force of proletariat rage. Ageing, out of work, he's a beast shambling towards extinction; the one act he believes is left to him - to find his daughter, rape her, then kill her and himself - is less the rejection of a fallen world than an angry reclamation of male potency. Though Roth and Stuart have altered Tom's father from the educated, middle-class architect of the novel to a working-class bloke made good (a necessity given the casting of Ray Winstone), lending the text a frisson of class tension, by the end his origins are unimportant - as are his reasons. He exists simply as an aggressor, the defining force within the microcosm of his own home. And Winstone's performance - steadfastly denying every charge, maintaining to the very end a tone of dismayed innocence ("You're sick," he murmurs, when finally confronted by his son) - is oddly convincing; one is reminded of Henry Czerny's portrayal of Father Peter Lavin in John N. Smith's The Boys of St. Vincent's (1993), another kindly monster.

Some viewers consider the film's lack of social context to be a failing, but I believe it heightens its effect. To link sexual abuse with wider social tensions, even tacitly, is too easy - as Noé seems to acknowledge with his film's final redemptive turnaround. It smacks of victim culture, in which responsibility can be endlessly deferred, and as such discounts the more disturbing possibility that evil is often localised, implacable, ultimately unknowable.

Many people, hearing the actor was stepping behind the camera, expected Tarantino-lite or ersatz Mike Leigh. Instead they found a bleak, thoughtful, quietly devastating film, heavily indebted to the art-house classics of yesteryear. A surprising result. But then, as Roth admits, wryly, "No matter what you do, for better or worse, your history goes with you."

Shane Danielsen: The film's most obvious quality is its sense of restraint. In many ways it's very austere.

Tim Roth: I hope so. The usual approach would be to get the camera right up close to the characters, to take the viewer into the thick of it. Because that's what we associate with realism these days: handheld, grainy, in-your-face photography. But I wanted to get very real performances - and I honestly don't think you can see a performance in this film - and then shoot them as beautifully as possible. I wanted Freddie Cunliffe to be everyone's 15-year-old son - I liked the idea of having this classical, David Lean-type landscape and then this sulky lout, shoulders slumped, head bowed, slouching through it.

Aesthetic considerations seem very important to you.

They are, but only in so far as they look back to the kind of cinema I used to see as a teenager, which I now miss terribly. Widescreen, never drawing attention to the camerawork, no fancy footwork.

Which film-makers in particular?

Tarkovsky, Visconti, Bergman - that great art-house tradition. I miss stillness, I miss silence. Death in Venice was an inspiration for its use of the camera and the silence - just people being people. Just watching the physical and verbal interaction of people is interesting, though film-makers today seem less and less willing to acknowledge that.

Having that huge [1:235] format meant I could set the camera and let the actors develop the frame and watch how they related to each other. So things would happen of their own accord, in a sense. And gradually, you get to sit at the table with the family - and then you realise you're sitting with the devil. Even the house, so squat and isolated in the landscape, becomes a strong character in its own right.

You changed a number of incidents from the book - the scene in which Jessie takes Tom to London to meet her lesbian lover, for instance.

We actually rehearsed it as it is in the book, but it didn't work. So instead I made it a scene about a first sexual encounter - though Tom has already had one of a kind when he looked through the window and saw his dad and sister together. For Jessie, it's like, 'Welcome to my nightmare' - and at the same time it's a desperate attempt to blow it apart and make it all go away. Also, it's an extraordinary bid by the older woman to help the girl and her brother whom she knows are in crisis. I think as it stands now it's much more complex and credible.

And Stuart was amenable to making changes?

Completely. Our way of working was very direct - I always said I'd give him first crack at the screenplay, but if it didn't work out I'd go to someone else, because he might be too close to it. But he turned in a terrific job. I pushed him on it. First, I set it in winter so he could look at it with fresh eyes. I made him go back and read the book again, and I also got him to read silent-movie scripts. Yet the screenplay is very different from the film - it changed again once the actors came in. You've got to be brave in an adaptation; you can't be a stickler.

Ray Winstone's performance is a lot more nuanced than viewers might expect.

When he first phoned me up and asked to have a go at it, I had my doubts. But he came in and said, "You know, it'd be great to play a good guy for a change." And I just thought, he's got it, he understands. Because the bottom line is that this guy doesn't see himself as a villain. And Ray just nailed it. He's one of the best actors I've seen.

The real standout, though, is Lara Belmont.

She's unbelievable - no previous experience, no training, nothing. I don't know what made her think she could be an actress, but she was right. The funny thing is, she's not all that interested in doing it again. She just said, "Give me a call if you're making another one," and wandered off.

You said the design changed during the shoot.

We were going to do all kinds of things that seem embarrassing to admit now. At one stage I wanted to evoke a nightmarish quality so every time a new emotional crisis was reached Tom would return to the house to find it slightly changed. It sounded very clever and ambitious, but really it was bollocks - it was me feeling acutely aware of my lack of experience, and trying to make myself think the way I thought a real director would. But one night Michael Carlin, the designer, and I went out and got pissed and confessed we both thought it was a load of arty wank. And that was that. What really made up my mind, too, were the performances. Day after day, watching the rushes, I was looking at things that seemed beautiful and completely honest - so why fuck with them? Why potentially ruin something wonderful, just for the sake of showing off?

You've often acknowledged a debt to Alan Clarke.

It's only because of him I'm sitting here. His example took me through the entire film. Alan was wonderful with actors - you felt clutched, held close, protected. He had this absolute love for his performers and that's the atmosphere I was trying to create on set. We were very careful with both the kids - even to the point of vetting the crew to make sure they were nice people. We knew there'd be a lot of tears, a lot of tough days, and we wanted people around them who'd be supportive. But it's not shot anything like the way Alan would have done it. I think he'd probably have done it for television - his whole thing was to take big subjects and get them out there to as many people as possible.

The kind of film-making you admire is thin on the ground. Even as an actor you must feel frustrated.

Absolutely. Often I find myself doing a film and realising one or two days into shooting that I've made a terrible mistake. But there are exceptions. I made a little film for Michael Di Jiacomo called Animals and the Toll Keeper - it was shown at Sundance last year. It's very poetic, very beautiful, which is probably why no one has seen it. But it just goes to show that there are people out there trying to make these kind of movies. We're just vastly outnumbered.