Casualties Of War

As well as an insane war, Apocalypse Now Redux reminds us of a time when cinema strove to be truly great. Philip Horne wonders if the new version adds to that greatness.

Seeing Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now when it first came out, at a packed afternoon show in September 1979 at the Ziegfeld, New York, sent one blinking out into a changed world - or at least with the sense that cinema could never again be the same. After the much publicised saga of its production, it turned out to be very different from the conventional epic most probably expected from the director of the Godfather films. This was an artist's crazy dive into the mainstream, 'kamikaze' film-making, to use the term Scorsese would coin for his all-out masterpiece of the following year, Raging Bull. A bloody, druggy, existential shaggy-dog story, Coppola's savage anti-epic plunged us violently into the dark jungles of Vietnam and the shambles of Cambodia, confronted us with a baffling, paradoxical phenomenon as mad as the war it seemed not just to picture but to embody. It may have been inspired by Joseph Conrad's classic 1899 novella Heart of Darkness, a fable of colonialism in the Belgian Congo, but it had little in common with, say, the BBC's decorous classic adaptations of the 70s (or Nic Roeg's pallidly literal version of 1994). A wild-eyed Coppola had indeed notoriously told the world at the preceding Cannes festival that 'The way we made it was very much like the way the Americans were in Vietnam. We were in the jungle, we had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little we went insane.'

The suspicion that madness had crept into Coppola's methods seemed to be confirmed by the unforgettable opening. In plot terms, our morally dubious guide Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) is waiting to be assigned his next mission - the assassination of a renegade American colonel, Walter Kurtz (Marlon Brando) - in a Saigon hotel room. But to begin with, still sitting in darkness, we don't know where we are. Before we can make anything out, helicopters loudly chop-chop-chop above us across the theatre (it was the first dramatic film to use quadraphonic sound). Immediately alarmed and groping for our balance, we see them float spookily in and out of frame as a strip of jungle flames up with napalm and the Doors break out with 'The End' - quite a number for the start of a film. Only gradually do we see Willard, in a haze of nightmarish overlapping dissolves, as he groggily recognises that this vision of past missions is prompted by the chop-chop-chop of the ceiling fan above his bed. When he gets up to look out of the window, we hear his situating inner voice say: 'Saigon. Shit. I'm still only in Saigon. Every time I think I'm going to wake up back in the jungle.' The sound of this narrating voiceover is extraordinarily intimate, like pillow-talk. As in Taxi Driver three years before, we have been made aware with startling rapidity that a virtuosic fusion of experimental effects is taking us inside the perceptual world of an unhinged American for whom the trauma of Vietnam is the stuff of recurring nightmares.

Apocalypse Now next shows us something more naked, more proof if needed of the madness in the Method. A nearly stripped Martin Sheen, actually drunk, as we now know, at Coppola's urging, postures violently, preeningly, smashes a mirror with a wild lunge and cuts his hand open, but continues with a horrifying scene that turns to bitter weeping and an agony of self-exposure and humiliation. The power of the film, as this made overt, would not only lie in its technical brilliance and originality, but in the reckless spiritual and psychological dedication, or abandonment, it required of its personnel. This was Method film-making: not just the actors living their parts, but the whole production recreating the insanity of Vietnam. Even before the full stories emerged of mental instability, heavy drug use, financial risks and the heart attack suffered by Sheen, it felt a dangerous film. It may offer the popcorn-eaters the story of a group of men on a quest and some spectacular scenes of combat, but cinematographer Vittorio Storaro's astonishingly rich and detached vision makes us see this panorama of futility with something like the wide-eyed stare of ironic disbelief that repeatedly appears on Willard's face as he contemplates the way things are.

Coppola's film contains no faked shots, no computer-generated images; it is concerned above all with recreating and vividly presenting, whatever the cost, the visceral, disorienting experience of the Vietnam War. And another part of its radical impact was its absolute refusal to discuss the rights and wrongs of the war, to contextualise beyond treating the whole conflict as total insanity. It was thus politically unplaceable, a film that corresponded to the Peace Movement's sense of the war as cruel and pitiful, yet in its respect and sympathy for the military and its humour clung to the human reality of the conflict (the original screenplay was by John Milius, a macho maverick not known as a man of the left, and Coppola himself had worked on the script of 1970's Patton). It was also prepared to countenance the unspeakable intoxication of killing.

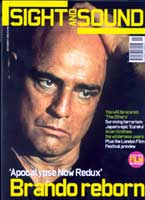

Like The Wizard of Oz and The Third Man, Apocalypse Now saves up our actual vision of its main bogeyman until daringly late in the film, surrounding him with a glamorous labyrinth of mysterious talk which raises the stakes. The Milius script had Willard and his assigned target Kurtz end up fighting together side by side against the Vietcong, but Brando's grotesque obesity when he arrived on location would have made such action sequences laughable, while Coppola was reluctant to throw away in boy's-own heroics the weight of significance the film had amassed. After such a build-up, the pay-off had to be hefty. Nothing but method soul-searching (hours of improvisation by Brando) and an infusion of high culture would do: T.S. Eliot was enlisted, the modernist admirer of Conrad's tale, who originally took Kurtz's 'The horror! The horror!' as the epigraph to The Waste Land (1922), his mythic, ironic poem of modern valuelessness and desolation. In his dark, echoing temple Kurtz quotes Eliot back, as it were, reading 'The Hollow Men' to a bemused Willard: 'This is the way the world ends/Not with a bang but a whimper.' He has on his shelf Jessie Weston's From Ritual to Romance and Frazer's The Golden Bough - crucial Waste Land sources and quests for primitive, essential myths. I remember thinking, 'This is the way the film ends? Not with a shootout but a tutorial?' But then Kurtz incites Willard to kill him and take his place in a violent ritual slaughter (intercut Godfather-style with that of a caribou by the Ifugao Indians). This is Weston's Fisher King, what Coppola described to Peter Cowie as 'the grand-daddy of all myths'.

In fact, as we learn from his wife Eleanor's heroically revealing book of diaries Notes: On the Making of 'Apocalypse Now' (1979), Coppola agonised almost to the point of madness over this climax. 'He said the more he works on the ending, the more it seems to elude him, as if it is there, just out of view, mocking him.' It wasn't only the ending - Coppola agonised about everything. In Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse, Fax Bahr and George Hickenlooper's superb 1991 documentary based on material shot by Eleanor, we see him as a Job-like figure or even a comic victim. Risking huge amounts of his own money, he is assailed by decisions needing to be made, bumps his head on equipment, confesses: 'My greatest fear is to make a really shitty embarrassing pompous film on an important subject. And I am doing it.' His wife's Notes sketch vividly his appallingly divided state of mind, which was partly responsible for the many delays before the film's release. And even in 1979 the 'finished' film appeared in two versions: in 70mm, at the Ziegfeld and other exclusive first-run cinemas, with a fade to black and no title; then on general release, in 35mm, with titles superimposed on shots of Kurtz's temple being blown up.

Apocalypse Now seemed a prime cinematic instance of the French poet Paul Valéry's dictum: 'A work is never completed... but abandoned.' And now the work abandoned to the public to make our own has been taken back and reshaped as Apocalypse Now Redux. Redux, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, means 'Indicating the return of an organ to a healthy state.' What was wrong with this acknowledged modern classic that needed to be fixed? Should we resent its repossession and alteration by its 62-year-old auteur and Walter Murch, one of its original editors and the architect of its still unsurpassed sound design? What moral right does an author have so to reassert himself?

Coppola in a 'Director's Statement' of May 2001 offers a justification in terms of his restricted freedom when first cutting the film. He describes his fear, with so much at stake, that 'The film was too long, too strange and didn't resolve itself in a kind of classic big battle at the end.' According to him, 'We shaped the film that we thought would work for the mainstream audience of its day... making it as much a genre 'war' film as possible.' Apocalypse Now Redux can't quite be called a 'Director's Cut', since the original versions were already that, but it has in common with most films to which the label is attached that it is significantly longer than the released version - by 50 minutes, making it 203 minutes in all. It should be said at once that fans of the 1979 cut won't find any of their favourite moments missing. And that Redux is at the very least absolutely fascinating.

Coppola's account of the original editing process makes it sound tamer and more craven than anyone seeing the film would have thought. Walter Murch, in conversation with Michael Ondaatje, has recently put it differently: 'Those previously missing elements were casualties of the hallmark struggle in every editing room: how short can the film be and still have it work?' Which seems to acknowledge that the film did work in its shorter, earlier version - as the test of time and its cult following might be taken to have shown. Correspondingly, the urge to restore the lovingly crafted elements which a hard discipline once judged inessential may be a temptation that ought to be resisted.

Coppola says that 'The new material is spread throughout the film', but the differences only really begin to bite at the end of the scene on the beachhead with the crazed Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall) and his airborne 'cavalry' of helicopters. In both versions the fascistic Kilgore bombs and strafes a Vietnamese village in what is the most hideously exciting scene in the film, blaring Wagner's 'Ride of the Valkyrie' on loudspeakers because 'It scares the hell out of Charlie.' He is prepared to land Willard and the crew of his navy patrol boat there, ready to go upriver, because he has recognised Lance Johnson (Sam Bottoms) - an ace surfer from California - among the crew and wants to see him surf. In the 1979 version we see two of Kilgore's men half-heartedly trying to surf despite heavy bombardment of the waves by the Vietcong ('Surf or fight,' they've been told), and Kilgore, insanely unflinching among the explosions that make everyone else dive for cover, telling the reluctant Lance it's time for him to do his stuff. Kilgore is then distracted by the eruption of napalm in the nearby jungle, which spurs him to his famous speech about loving 'the smell of napalm in the morning' and the strikingly bathetic line: 'Some day this war's going to end.' The next thing we see is the boat going upriver with its crew, Lance's suicidal surfing duty apparently forgotten, and we hear Willard's voiceover reflecting on Kilgore's craziness.

In Redux Coppola and Murch fill in what lay behind this transition. Kilgore keeps up the pressure on Lance, but Willard takes the initiative, telling Lance to 'Get the fuck out of here' under cover of incoming fire. They make a farcical escape, stealing Kilgore's surfboard, piling into their patrol boat and laughing manically as they surge upriver to the accompaniment of wild native music. This makes Willard more sympathetic and Kilgore's madness more actively threatening. And before long, after Chef (Frederic Forrest) begins his mango fantasy (there in 1979) about meeting Raquel Welch in the jungle, Redux has the boat hiding from Kilgore's helicopters, which hover above broadcasting his God-like voice as he dementedly demands the return of the stolen surfboard. Willard is again here gleefully complicit with the boat's crew, as never in 1979.

How does this change the film? Coppola is certainly right to say that 'There's more camaraderie now. Willard jokes with his crew... They all start off kind of normal - and that naivete helps underscore the tragedy of what befalls them.' The blast of humour is a relief from Kilgore's oppressive mania and in a traditional narrative manner establishes the likeability of the crew so we care more later. But what the change causes us to lose is the disconnectedness, the radical sense of randomness of the 1979 transition. Who needs to know, 1979 asks us, whether or not Lance surfs? The point we are left with is that Kilgore is mad enough to cause such intoxicating carnage simply because the waves near this village are 'Tube City'. And the laughing Willard of the surfboard escapade is not the scary madman we've seen in the Saigon hotel room, nor the alienated spectator of most of the journey. The 1979 film also told us we didn't need to know much about the crew in the conventional expository way of human interest; they were seen with a more alienated, less apparently affectionate eye, one which corresponded to Willard's numbness and was part of the original film's shock value.

The next big addition again restores connections between parts of the river journey, making it less aggressively episodic. The original Playboy playmates sequence is, as the young black crew member Clean (Laurence Fishburne) says, 'a bizarre sight in the middle of this shit'. On a floodlit stage, surrounded by a prophylactic moat, the troops are rewarded by a Las Vegas-like display of gyrating female flesh and driven into a frenzy of lust - to the riotous point where the playmates have to be evacuated by chopper. In 1979 the boat soon moves on upriver, and apart from Chef's mention of his fondness for Miss December, the playmates evaporate.

Redux provides a connected story and tries to turn the playmates into substantial characters. It first expands Chef's mention of Miss December into a full-scale discussion by the crew of the cult of Playboy, culminating in the anecdote of an American soldier killing a 'gook' who interfered with a copy of the magazine. In 1979 Willard's boat passes the body-strewn site of some terrible conflict and radios to Medevac to send aid, without getting any response. This failure slips by unremarked, but Redux gives it a full-scale correlative a couple of minutes later when the boat arrives at a bombed-out Medevac camp: 'What a dump. No wonder I couldn't get them on the radio.' The Playboy helicopter is stranded here and Willard (another ingratiating favour to the crew) strikes a deal with the playmates' manager (Bill Graham, real manager of the Grateful Dead): two hours with the playmates for two barrels of fuel. There follows a long double sex scene where Chef and Lance, in a helicopter and a hut respectively, with Clean waiting impatiently in the rain, role-play with their playmates.

The sex scene is in the improvisational mode of the Brando scenes at the end - the girls describe their alienation from their bodies, the emotional effects of the Playboy culture that has made them sex objects. But as they talk, the men aren't listening, are murmuring empty assent and treating them precisely as fantasy objects. Finally Clean bursts in impatiently and a dead body is discovered. The scene closes with the playmate asking Clean, 'Who are you?', and his reply, 'I'm next, man.'

The new material again amplifies the significance of the crew, making them the focus in a digressive scene where Willard is not even present (as he always is elsewhere). It offers, of course, an extension into sexual politics of the 'theme' of the film, as Coppola says: 'In their way, the girls are the corresponding characters of those young boys on the boat, except they're being exploited in sexual ways.' But while the scene is perfectly consistent with the film's moral and political concerns, it fails to comply with its formal rules of engagement, its filtering of everything through Willard's blankly ironic reaction. For many I suspect it will feel slightly dated and redundant.

Perhaps the most interesting effect it has on what was already there in 1979 stems from the fact that the scene immediately precedes the My Lai-like massacre on the sampan. It closes on Clean's sexual frustration - and Clean is the one who shortly thereafter begins machine-gunning the innocent Vietnamese. So it motivates, perhaps, though it also reduces the shock of the slaughter, which previously came out of the blue. Do we want to be asking, what if Clean had been first to go with the Bunnies?

The third and longest of the four main new elements is the controversial French plantation scene, which comes in Redux soon after the death of Clean in a hail of bullets from the jungle. In 1979 the patrol boat comes through thick mist towards the huge tail of a crashed plane sticking surreally out of the river and glides beneath it, directly passing on to the tribal attack with arrows and spears. In Redux there's even more mist, in which the boat comes across an incongruous relic of Vietnam's colonial past: a ruined but still inhabited plantation where a French family have clung on with their own private army, killing all who attempt to take it from them.

Once they've laid down their arms the Americans are welcomed into this strange outpost of a non-existent empire. Clean is buried with military ceremony in a scene whose mournful music is strikingly unironic, reminiscent of Coppola's Gardens of Stone (1987) and its touching treatment of the burial of the Vietnam dead. Willard sees that a woman, later identified as Roxanne (Aurore Clément), is watching from a balcony. There follows an elaborate formal dinner during which Willard's French hosts argue about the colonial past and Hubert de Marais (Christian Marquand) fiercely defends the importance of place and home. Their estate in the jungle, not France, is home to these expatriates: 'It's ours, it belongs to us. It keeps our family together. Whereas you Americans are fighting for the biggest nothing.' Then Willard is left alone with the ethereal Roxanne, who tells him, 'You're like us; your home is here', takes him upstairs to bed and shares her drug pipe with him. (The scene, incidentally, is overlaid with a regrettably soupy 'love theme' found among Carmine Coppola's effects.) Undressing behind the gauze of a mosquito net, Roxanne says, 'There are two of you, don't you see? One that kills, and one that loves.' We next see Willard on the boat in the mist as the spear attack looms.

In her Notes, Eleanor Coppola writes about her husband's frustration with the shooting of this scene. And in Hearts of Darkness the director said he cut the sequence because he was 'angry' at it, though he now states: 'I always loved this scene because here, the men on the boat truly leave civilization behind, and go back in time.' The scene obviously enables Coppola to introduce a contextual debate about 'Why Are We In Vietnam?', to borrow Norman Mailer's question. It suggests a Godfather-like truth about local or family attachment as the ultimate source of meaning, which anticipates Kurtz's radical resettlement in the jungle. It also makes explicit Willard's divided nature, again making him a closer double for Kurtz.

But probably the most important aspect of the scene is the question of whether it 'really' takes place. Walter Murch calls it 'this apparition of a plantation' and does not seem convinced, even now. But if these aren't 'real' people, the problem is whether in a film whose surrealism is so strong a part of its dark satirical thrust - which depicts so many events that ought to occur only in dreams, like cattle and boats hoisted in the air by helicopters, dancing girls dropped out of the sky - we want to fudge matters by having yet a further level of unreality? The length and the complication of the references make the scene an unlikely dream for Willard: does he dream in French?

On the other hand, the dreamlike weirdness of the French plantation does prepare us for the bizarre world of Kurtz's compound, which is where the last of the significant extra scenes comes in. Willard, bewilderingly seized by Kurtz's Montagnard minions, is literally turned upside down and caged. Redux, like the 1979 version, has him visited by a sinisterly looming Kurtz in the night, his face painted green. Kurtz tosses Chef's severed head into Willard's lap. Next, 1979 had a scene of dawn on the river, and a prostrate Willard carried into Kurtz's temple. But before this Redux reintroduces another morning scene, one of the last cuts made in 1979 to keep the running time down, where rays of sunlight shine into Willard's dark cell, interrupted by laughing, chattering children peering in at him. Among the children we discover Kurtz - the one time we see Brando in daylight. He opens the door and reads Willard a report from Time magazine about a US intelligence analyst returning from Vietnam to tell President Nixon that 'Things felt much better, and smelled much better over there.' Kurtz then asks Willard, 'How do they smell to you, soldier?' He tells Willard he is free to move about the compound, but Willard collapses.

This gives us, as Murch says, a Kurtz for once not hidden in darkness (which always did seem a cheat, a mere evasion of Brando's bulk), a Kurtz 'coherent, ironic and authoritative'. As direct political commentary, it fits in with the French plantation debate, but also with Kurtz's final words, dictated to a tape machine, before his killing: 'Their commanders won't allow them to write 'fuck' on their airplanes because it's obscene.' Coppola says, 'I think this scene contributes to the sort of anti-lies theme, and sets the rationale for his behaviour, or for his madness.' The 'anti-lies theme' - a point on which Willard and Kurtz are in agreement - is clearly stated near the end of Kurtz's final full speech: 'There is nothing I detest more than the stench of lies.' The scene bears out with welcome sharpness, like nothing else in 1979, the assertion by the photojournalist (Dennis Hopper) that 'The man is clear in his mind but his soul is mad.'

Walter Murch has found the perfect pitch for Apocalypse Now Redux: 'Definitely this is the funny, sexy, political version of Apocalypse Now.' The new scenes justify the description, but I think there remains some question about whether Coppola is right that 'This version is Apocalypse Now at its greatest potential.' In due course, I suppose, DVD will allow us to drop the French plantation scene, or just the love scene. On the other hand, whatever one's reservations, it must be said that the new film is an extraordinary, enlivening experience, especially on the big screen. Even for the jaded spectator, the knowledge that it has been so seriously re-edited gives one new, freshly shockable eyes.