An Eye For An Eye

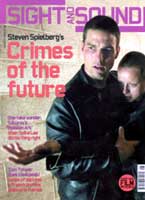

In his future cop-on-the-run thriller Minority Report, Steven Spielberg pushes himself to revel in the sordid mess of human dysfunction, argues Nick James

A pair of scissors, someone's glasses, a merry-go-round: these old-fashioned objects feature in the opening credits of Minority Report, Steven Spielberg's new science-fiction blockbuster. Still apparently useful in the year 2054, they tell us we are about to inhabit a traditional murder mystery as much as a future world. Pictures of these things float up to a ceiling screen out of the minds of three psychic beings, known as precogs and connected together in an egg-shaped flotation tank called the Temple. A sequence of distorted, high-contrast images, in which a comfortably-off middle-aged man called Howard Marks (Arye Gross) commits a crime of passion against his wife and her lover, sends Agatha (Samantha Morton) - the most important of the precogs - into spasms. Looking, in her liquid nutrient bath and feeding suit, like a plausible mate for The Man Who Fell to Earth, her eyes flip open and the oracle speaks: "Murr-durr".

No hot new sci-fi devices show up in these previsions. Killings in 2054 are performed in resolutely arcane ways: stabbing, strangulation, drowning or even shooting with an automatic pistol. All sorts of horribly neat new weapons have been invented - "sick sticks" that make you vomit at a single touch, air-pressure shotguns that bowl you flat and winded - but they are exclusive to the security forces of the Pre-Crime unit and the Justice Department. At least they are in Washington DC, the only city so far where all murders can be predicted and their perpetrators arrested before they've committed the act. The murder rate has consequently dropped to zero. Only unpremeditated killings are now envisioned, and even these are swiftly prevented, their would-be perpetrators filed away in (that good old comic-book concept) "suspended animation".

To see how it all works we cut from Agatha's gaze to more eye imagery: two billiards-sized balls are machine carved side by side out of wood; one bears the name of the crime's victim, the other of the perpetrator. They roll down separately into the waiting palm of Pre-Crime's ace cop, Chief John Anderton (Tom Cruise). He reads out the names to televisually linked "witnesses" and downloads the precogs' predictive images on to a transparent wall screen where he uses special gloves to manipulate them - somewhat like an orchestra conductor (to the soundtrack of Schubert's Unfinished Symphony) - seemingly able to survey a third dimension by slightly altering the POV on the scene. He's searching for clues to the location where the crime is to be committed. All this makes a gripping opening sequence because there's only minutes until the crime is due, and the scene is hard to locate.

By the time you're reading this, though, you will probably have seen at least the trailer for Minority Report and will know that it is, at spin level, a chase movie with the catchphrase "Everybody Runs", and that John Anderton soon becomes a victim of his own system when the precogs foresee him murder someone he's not yet met. If you've seen no more and want to preserve your innocence of the film's convoluted plot, please be warned off the precognitions below. For Minority Report is about almost nothing if not its crammed universe of visual clues to the future, to be examined here as well as enjoyed.

The true catchphrase of the film should be the one Agatha whispers to Anderton just after the inner sanctum of the egg has been briefly invaded by FBI investigator Danny Witwer (Colin Farrell), who wants Anderton's job and is looking for the flaw in Pre-Crime. "Can you see?" she says as soon as she and Anderton are alone, as she projects a long-ago prevented pre-crime from her cerebral vaults on to the ceiling screen. A woman is being drowned by a hooded man and Agatha's "Minority Report" of this crime (one that disagrees with the reports from the two other precogs) will prove the key to unravelling all that's happening to Anderton. In a film hung up on the iconography of vision, the ability to foresee the future - and review the past - becomes a metaphor for both the artistic and film-consuming processes. Who has the gift of vision, the film wonders? What use is it to know our fate? What help to relive the past?

Eyes in 2054 are no longer the windows of the soul (if souls there still be) but genetic-identity documents, constantly scanned and recognised wherever the citizen goes. When Anderton is on the run from his own men, moving-image billboards for The Gap, Lexus and Guinness greet him by name (taking product placement to new intertextual levels); moving-image newspapers flash his picture under the headline "Pre-Crime Hunts Its Own". The film's ongoing subthemes - addiction, grief and addiction to grief - are pursued through modes of visualisation with the addiction to images as the primary metaphor. John Anderton is haunted by visions of his past negligence. We see him as a typical Tom Cruise variant: black-clad, chin jutting, a leather shadow always either running or stalking, his meaty arms bleached to the colour of fat by high-contrast cinematography. The book on Cruise has it that he's a wooden or blank actor, but here he seems to have perfected the role of the modern action hero as cipher. We've become so used to watching him in these driven action roles that it's easy to make him our own eyes and ears. Could it be that he's now so confident and good in these parts, he's happy to leave the acting fireworks to those around him? (Certainly he's very generous to both Morton and Farrell.) Whatever the case, the cop he plays is no replicant.

What Anderton is, as his mentor Lamar Burgess (Max Von Sydow) tells us, is Pre-Crime's poster boy. He became involved in the Pre-Crime experiment because his nine-year-old son Sean was abducted from a public swimming pool - while Anderton was holding his breath underwater - and was never seen again. Anderton is pivotal to Burgess' attempt to convince the entire US to adopt Pre-Crime. His very public loss of his son makes the public believe in his sincerity. But the same loss has left him damaged. Before he's even accused of future murder he can be found running through the rain in a lowlife area known as the Sprawl, where he's greeted from the shadows by his "neuroin" dealer, who jives on about vision, even quoting that old chestnut "in the kingdom of the blind the one-eyed man is king", before removing his shades to reveal two cavernously empty sockets. Anderton uses the designer stimulant he buys to enhance the experience of watching holographic home movies of Sean and of his estranged wife Lara. His visions affect him as powerfully as the murders affect Agatha.

The downbeat existential dilemma of the haunted cop is, of course, a hard-boiled crime-fiction staple. The hero is usually a damaged figure who has turned to detective work out of some romantic idea of putting things right. Minority Report's restless images of a colour-bled city of repressed violence, often shrouded in rain, evince a palpably queasy neo-noir dystopia. Immediately we think of Deckard in Blade Runner (which, like this film, was based on a story by Philip K. Dick), the 1940s private detective reborn to hunt replicants. But with the scissors, the glasses and the emphasis on grand residences and fatal objects, there's also an element of an earlier breed of detective fiction here - the country-house murder mystery. Maybe it's not for nothing that the queen bee of the precogs is called Agatha.

As I've already suggested, the world in the precogs' heads seems more like our own world, whereas their predictions are relayed to the 2054 world of discreet special effects. Plugged into their visualising system, they seem like future consumers of virtual reality. In other words, the precogs are us. It's a sign of Spielberg's deepening knowingness that he can so blatantly hint that we are powerless deities of our own entertainment world. We the viewers watching the movie feel the hurtle of future events with a similar abandoned sensitivity to Agatha's. Late in the film she and Anderton visit a virtual-reality pleasure palace in which punters can be wired into any fantasy they like. This idea of the future consumer as a figure whose inner urges are both predicted and supplied to them is perhaps the central doom of Spielberg's 2054. Dreams or visions will no longer be our own, or indeed originated through any recognisable version of the imagination. In that sense, the supposedly free citizens may not be much better off than the filed-away felons, for both have their sense of reality controlled, their imaginations channelled. Coming from a major popular film-maker like Spielberg, there seems to be an edge of mea culpa to all this fretting about future punishment and future entertainment.

Spielberg seems to have arrived at his 2054 out of a need to make the setting of Minority Report substantially different from the key Hollywood-blockbuster future worlds of recent times. Though the viewer can't help but recall, at different points, Blade Runner (1982), Twelve Monkeys (1995), Strange Days (1995), The Fifth Element (1997) and Fight Club (1999), to name only the most obvious similar films, what's most impressive about this future Washington DC is its distinctive combination of hi- and low-tech. Traffic problems seem to have been solved by a Metropolis-like system of remote-controlled bubble vehicles in chutes and overpasses, but the Pre-Crime cops use jet-packs that are almost laughably crude in their operation - as Anderton demonstrates when he sees off a bunch of his former colleagues by piggy-backing on one of them. It has been well advertised that Spielberg called together a group of expert futurologists (including Generation X author Douglas Coupland) to predict what the US of 2054 might be like, and in terms of plausibility - especially in the new technology's potential for glitches - it feels suitably gritty. To emphasise the healthy mistrust of the new devices, objects such as umbrellas and bunches of balloons prove more effective than sci-fi inventions when it comes to avoiding surveillance.

It's as if Spielberg, after A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), has become hyper-sensitive to sci-fi's ubiquity. After decades of Hollywood SF blockbusters, the core audience knows the ropes as well as it knows the basic rules of PlayStation X games. Almost everyone seems now to be a science-fiction expert of one kind or another. Even if you fail to get a buzz out of even a high-quality SF film such as The Matrix, you don't have much choice about experiencing science fiction. New realities and machines keep upsetting the world-orientation devices of all of us, even non-gamers and technophobes.

A central dilemma of the cool-looking sci-fi movie is that it can become a Baudrillardian self-fulfilling prophecy. Through the seductiveness of its look and the scale of its imaginings, a movie like Blade Runner, perhaps meant on one level as a warning to the world, will prove so inspirational to industrial designers and architects that the world begins to shape itself in the film's image. In downplaying the James Bond boy-toy version of our future, the harsher world of Minority Report is perhaps only responding to the temporary bursting of the communications industries' bubble. But in its emphasis on genetic experiment (the three precogs are the survivors of genetic work done to help the damaged children of drug addicts), the film shows its awareness of the potential of the human genome project to provide a biological form of future shock.

Minority Report couldn't be further, then, from the innocent 1950s pulp with which Spielberg grew up, from the roll call of spaceships, zap guns, robots, weird planets and alien creatures that informed Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) as much as E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982). Anyone who collected comic books back then had probably discovered most of the plot wheezes of sci-fi before progressing to the novels the comics stole them from. The books with the predictive political power were mostly written outside the science-fiction canon. One reason why the once highly regarded works of Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke are no longer adapted into movies is their lack of political foresight. There's nothing in them to match the predictive powers of, say, George Orwell's 1984.

But there is at least one obvious exception: Philip K. Dick. Only his amphetamine-fuelled lexicons of paranoia match Orwell's dystopian vision. And it's not just landscapes of power and control that Dick and Orwell have in common. The influence of hard-boiled detective fiction that emerges in Dick's neo-noir approach to both Minority Report and Blade Runner (though Spielberg's is a more mobile, viscous, vérité version of neo-noir than Ridley Scott's future dazzle) can be felt equally in 1984. Isn't Winston Smith himself a version of Hammett and Chandler's existential loners? In their vast elaborations on what is a very threadbare Dick story here, screenwriters Scott Frank and Jon Cohen seem to have imbibed a draught of Orwellian thought crime, especially in their treatment of the surveillance theme. And it was Orwell, in an essay called 'The Decline of the English Murder', who extolled the pleasures of reading about true crime, of dipping into the seamy side of life for perverse pleasure. Spielberg here seems to have accepted his invitation, revelling in the sordid mess of humanity.

This is easily the most comfortably dark and pessimistic film Spielberg has yet made. In the scenes of Anderton's personal desolation you can almost feel the director pushing himself to go as bleak and black as David Fincher. The reason he can allow himself to be so grim is perhaps because the story offers so many opportunities for slapstick light relief. There's a Hitchcockian dark humour that constantly mocks the film's obsession with seeing. Anderton evades capture long enough to visit the Pre-Crime scheme's reluctant originator Dr Iris Hineman in her Greenhouse full of lethal hybrid plants (Raymond Chandler's hothouse in Agatha Christie's garden). It's she who tells him about the possibility of the precogs disagreeing and how this has been hushed up. But her most crucial bit of advice is to suggest he should get his eyes changed for someone else's so he can return to Agatha undetected. In a deliciously camp horror scene, renegade eye surgeon Dr Solomon Eddie (Peter Stormare) injects Anderton with anaesthesia before reminding him they know each other. It was Anderton who ruined the former plastic surgeon's life in Baltimore by putting him away. Eddie's revenge, which I won't describe here, is suitably revolting. Later, when Anderton is trying to break in to see Agatha, he gets out his old eyes from a plastic bag to gain entry but drops them, and they roll down a ramp towards a grating with Anderton chasing.

By this time the cop has had his face temporarily uglified to avoid being recognised. This is something that now seems to be written into Tom Cruise's contracts: his face must at some point be distorted, whether by the masks of Mission: Impossible II, the disfigurement of Vanilla Sky or the temporary make-over here. Whether what's behind this reverse-Dorian Gray complex is anxiety about his pretty-boy status or just coincidence is between Cruise and his analyst. What's for certain is that Cruise plays the slapstick well, with the appropriate deadpan of the dumb cluck.

There's a curious lacuna, though, within Anderton's eye-swap. After the operation he is left to recover and told not to take off his bandages until time's up, or he'll be blind. With a couple of hours still to go, Pre-Crime cops scan the building he's holed up in for "warm bodies" and send in mechanical spiders designed to read the eyeballs of everyone inside. So fearsome are these devices that all the citizens comply at once. Anderton almost evades them, but is forced out of a bath of ice and surrounded; one spider then lifts his bandage and reads his eyeball - thereby misidentifying him. Anderton ought by logic to become blind in one eye, which the earlier "one-eyed man is king" quote would seem to presage. Is this a plot strand that got dumped?

Before the operation we see Anderton's eyelids being pinned open in a fashion that irresistibly reminds us of Alex the droog forced to see revolting images in Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (1971). Since Minority Report was already shooting while A.I. was being edited, it's become commonplace for critics to see Kubrick in every frame, matching the boy who goes missing in A.I. to Sean here. Certainly there's a Kubrickian logical clarity and coldness about the project and it has the architectural finish of a Kubrick movie. But Kubrick's presence here is as one among many, including Hitchcock and Lang as much as Ridley Scott and David Fincher. One of the problems of writing about Spielberg is that his films are littered with so much resonating movie stuff - both objects and concepts - yet he's never given the credit of being a film buff that goes to his contemporary Martin Scorsese. Minority Report is as smart in its movie referencing as anything in Scorsese's canon. Why else would Samantha Morton so resemble Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc once she gets out of her nutrient suit?

Cruise and Spielberg, two different varieties of control freak, prove a winning combination. Cruise is seemingly all out for the charge of the ride, for film-making as a risky extreme sport that leaves subtext gasping by the side of the road. Spielberg is more the avuncular orchestrator of other people's skills, ideas and emotions for a grand, resonant purpose. The vulnerable English weirdness of Samantha Morton as Agatha, stumbling through the real world wondering "is it now?" and helping Cruise to second-guess the future, adds a more unstable force, a psychological recklessness that seems the apt equivalent of Cruise's physical derring-do. What Minority Report does best is what Spielberg himself does best. It borrows, steals and cannibalises ideas from every quarter and fuses them into a sleek new whole. This is all one can ask of the makers of today's big-budget blockbusters: that they know how to hothouse hybrid forms from old offshoots. If Kubrick's shadow falls on Spielberg, it's because Kubrick is one of cinema's true originating visionaries, whereas Spielberg is not (quite). But the time for true originating visionaries may be over. We're in an age of orchestrators and arrangers, directors who can translate the ideas of many into one big experience. If the audience is Agatha, then Spielberg is Anderton wearing his special gloves and manipulating the visions of others.

With the help of Cruise, the screenwriters and the committee of futurologists, Spielberg seems to have discovered that we live in truly dangerous times, and that the future may be darker yet. The former king of happy Hollywood, of mom and apple-pie aplomb, is into his King Lear phase. He's made a movie about grief and drugs with more forward propulsion than a cruise missile. Frank and Cohen's script has done its best to lead a perhaps wary director into territory fraught with gloomy prognostication. Spielberg has responded with courage and froideur, but he's still Spielberg. The nuclear family remains the ne plus ultra in this future world (it's all Anderton dreams of). The ideal woman is again a pregnant mother whose encircling arms provide the only safe place. And the perfect locale for psychic geniuses turns out to be a version of Wordsworth's cottage, nestling on an isolated island and crammed with great literature.

In this top-class genre movie, Spielberg shows us a future whose plausibility and political resonance is to be welcomed. It's an apt moment to consider whether the western world can prejudge criminals of intent who are not yet perpetrators - suspected terrorists being a case in point. But if there's one thing that's obviously missing from this 2054 that was predicted in Orwell's 1984, it's Bush the younger's perpetual war on terrorism. One might ask, why set such a film in Washington DC if you're not going to bring some international context into play? If the US remains as politically insular in 2054 as it is right now, then this is indeed a future worth avoiding.