Funny Peculiar

The St. Trinian's films may be the first we think of, but Alastair Sim was a vastly versatile actor without whom the landscape of British cinema's heyday would be a less joyful place. Michael Brooke pays tribute to an eccentric master.

If ever an actor transcended his medium, it was Alastair Sim – not least because that medium often betrayed distinct uncertainty as to how best to use him. Though he made more than 60 films, most are resoundingly middlebrow comedies and thrillers, and there are surprisingly few enduring classics given his richly merited reputation as one of Britain's funniest actors.

His film career spanned more than 40 years, though the high point was the 'green period' bookended by Green for Danger (1946) and The Green Man (1956), the former's inept sleuth Inspector Cockrill and the latter's ruthless assassin Harry Hawkins being two of his best-remembered roles. He was also Wetherby Pond, the increasingly rattled headmaster of single-sex Nutbourne College, looking on in horror at an invasion by Margaret Rutherford, Joyce Grenfell and several dozen girls in The Happiest Days of Your Life (1950); the much less flappable Miss Fritton, founder of the anarchic girls' school first seen in The Belles of St. Trinian's (1954); and the cinema's unimpeachably definitive Scrooge (1951).

But this is just one wing of Sim's gallery of grotesques. A less familiar quintet might include dour Scottish preacher Angus Graham in The Wedding Group (1936), mesmerised by a lit taper while composing a sermon on hellfire and damnation ("think that this burning taper was your finger, that this finger was on fire, that your body was on fire, that your sooooooul was on fire – that, my brethren, is Hell!"); disaffected communist Max in Climbing High (1939), posing in a leopard-print loincloth for the 'before' picture in a muscle-building commercial; the blithely incompetent Sergeant Bingham of the Inspector Hornleigh films (1939-41); pompous finance minister Sir Norman Barker in Innocents in Paris (1953); or the elderly lecher General Suffolk in the television play The General's Day (1972), his fingers dancing a pirouette on the hem of Annette Crosbie's knee-length skirt during a supposedly innocuous conversation.

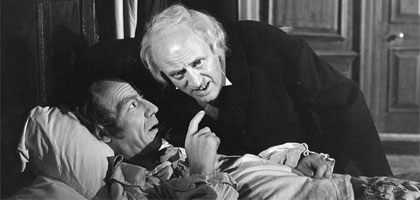

Sim was the eccentric uncle of British cinema. His postwar roles almost invariably put him in a position of authority, though his grip on power was usually tenuous, its potential slippage foreshadowed by frightened-rabbit panic behind the eyes or a flickering tongue behind a nervous, snaggle-toothed smile. Physically, he was so perfectly built for comedy – with that great bald dome (already present in his mid-twenties), heavily lidded eyes, protruding lower lip and gangling frame – that it's hard to credit he didn't recognise his gifts until well into his thirties.

Had he started filming just a few years earlier, he could have been a great silent comedian. Consider the priceless scene in Green for Danger where, half way through reading a whodunit, he sneaks a look at the climactic revelation, his face switching seamlessly from smug certainty through surprise, bafflement, disappointment and resigned acceptance that his deductive powers aren't as acute as he'd like to believe. Or there's his single-take essay in self-conscious surreptitiousness in Laughter in Paradise (1951), where he tries to get himself arrested for shoplifting, his body language betraying both his inexperience and his disgust at the depths to which he has sunk in order to inherit a fortune.

But the silent screen would have denied Sim his crowning glory: that extraordinary voice. Only Gielgud rivalled his tonal control and sensitivity to the musicality of the English language, and it comes as no surprise to learn that Sim was a successful elocution teacher before he turned to acting. His horrified realisation that the Ministry of Education has committed "a most appalling sexual aberration" in The Happiest Days of Your Life is made doubly delicious by the flawless rendition of every vowel, diphthong, consonant or plosive. His dictation of his novel Bloodlust in Laughter in Paradise filters hard-boiled American slang through incongruously patrician tones to even more hilarious effect, and his voice required surprisingly little modification to be wholly convincing as St. Trinian's headmistress Miss Fritton.

Born in Edinburgh on 9 October 1900, Sim grew up above his father's tailor's shop. At 14 he joined the family business, but was sacked for incompetence, and a subsequent job at men's outfitters Gieves saw him demoted to tie salesman as this was the one item of clothing he could package. He studied analytical chemistry at the local university and after a year's itinerant life in the Highlands returned to Edinburgh and a desk job in the Borough Assessor's Office. By 1925 he was running a drama school while simultaneously holding the post of Fulton Lecturer at Edinburgh's New College, where he achieved a considerable reputation as an elocutionist. Reading the many affectionate anecdotes in his wife Naomi's memoir Dance and Skylark (1987) produces images of the young Sim struggling with suit, string and paper, or training parsons in how best to enunciate a sermon, that could well have been drawn from his films.

Several verse-speaking competition medals later, and on the cusp of his thirtieth birthday, Sim asked the writer John Drinkwater for advice on how to become a director. Drinkwater suggested he should stick to acting, and his connections secured Sim a part in a 1930 Savoy Theatre production of Othello with Paul Robeson, Peggy Ashcroft and Ralph Richardson. Sim's stage career blossomed, and in 1932 he joined the Old Vic.

He still thought of himself as a serious actor, and it was only when a comic performance as a pompous bank manager in a 1934 production of Hubert Griffith's Youth at the Helm led to his first film offers that he began to specialise in comedy. He made his screen debut in 1935 and played his first lead role in the following year (in the musical The Big Noise, in which he sings about the joys of capitalism to a passing goat), though he more usually provided scene-stealing distraction while bigger names such as Jessie Matthews, the Crazy Gang or Gordon Harker kept the plot motor running.

While it's hard to trace Sim's roots from his postwar performances, those of the 1930s leave little room for doubt. His first screen role, as the sidekick to Basil Sydney's Inspector Winton in the humdrum quickie The Riverside Murder (1935), was originally conceived as a Cockney, but Sim's casting led to a hasty rewrite, his Sergeant 'Mack' McKay undoubtedly hailing from north of the Tweed. The next few years saw him playing Mac (Late Extra, 1935), 'Mac' MacTavish (Troubled Waters, 1936), Angus Graham (The Wedding Group, 1936), Joshua Collie (The Squeaker, 1937), Lochlan Macgregor (This Man Is News, 1939; This Man in Paris, 1940) and Sergeant Bingham. The name notwithstanding, Bingham was the apotheosis of Sim's slapstick Scotsmen, a fey, befuddled aide to Gordon Harker's gruff Inspector Hornleigh in the eponymous film and its two sequels. Sim's screen persona then migrated southwards – and, aside from isolated one-offs such as the laird in Geordie (1955), the relocation was permanent.

The transitional film was Cottage to Let (1941), Anthony Asquith's adaptation of a stage hit, with Sim recreating his role of Charles Dimble for the big screen. Initially Dimble seems cut from the same cloth as Bingham, though there's something slightly off-kilter about the accent and the chortling bonhomie, suspicions that are confirmed when he sheds both and reveals himself as a ruthless Nazi agent. Although Sim had played sinister roles in the past, this was something new, an alarming metamorphosis into evil that is barely mitigated by an eleventh-hour revelation that he was with the Allies all along. As Pauline Kael wrote of The Green Man: "It is unlikely that anybody in the history of the cinema has ever matched his peculiar feat of flipping expressions from benign innocence to bloodcurdling menace in one devastating instant."

Sim's gear changes weren't always so dramatic, but his unpredictability makes him a compelling presence even in the most innocuous fluff, and an unforgettable one in the films he made for Frank Launder and especially Sidney Gilliat. Gilliat first directed Sim in Waterloo Road (1944), where his Doctor Montgomery provides a running commentary from the sidelines on the film's central soldier-wife-spiv love triangle. It's a respectable enough performance, but Gilliat was dissatisfied with the casting, believing that Sim was too fundamentally eccentric to get across his original conception of a local philosopher dispensing homespun wisdom.

However, Gilliat also realised what Sim could bring to the right vehicle, and came up with one in Green for Danger. He and co-adapter Claud Gurney reinvented the protagonist of Christianna Brand's murder-mystery novel wholesale, and it's clear from the shooting script's introductory description of Inspector Cockrill as "a consciously eccentric character who delights in disconcerting people by behaving as little like a policeman as possible" both who was envisaged for the part and what he was expected to deliver. Gilliat plays the action entirely straight up to the point of Cockrill's arrival, after which the film strikes out into far more intriguing territory, especially as it becomes increasingly clear that Cockrill's air of intellectual superiority is based on supreme overconfidence and, ultimately, self-delusion. The script reveals that dialogue and actions were carefully pre-calculated, but Sim's vocal delivery would have needed musical notation to do it justice.

This performance established Sim both as a box-office draw and as someone peculiarly suited to embodying the uncertainties of the immediate postwar era. Most of the comedies in the 'green period' have been mentioned, but to them can be added Hue and Cry (1946), his only Ealing comedy, in which his writer is horrified at the news that his boys' comic is being used as a conduit for criminal messages; Folly to Be Wise (1952), in which his well-meaning padre causes chaos when put in charge of the entertainments at an army camp; and Lady Godiva Rides Again (1951), with his film producer Hawtrey Murington delivering an analysis of the shortcomings of the British film industry that could have been written last week.

Sim showed a more sombre side in films like Gilliat's London Belongs to Me (1948), where his fake psychic Henry Squales is a genuinely seedy and unpleasant figure, topped with a comb-over and ending a séance drenched in sweat (or ectoplasm?) before plotting to fleece Joyce Carey's middle-aged widow. Asset-stripping of both the financial and emotional kind is also at the heart of Scrooge, where Sim's incarnation of Dickens' curmudgeon clearly relishes his own callousness. In Captain Boycott (1947) he's Father McKeogh, a 19th-century Irish proto-Gandhi whose gospel of non-violent civil disobedience eventually bears fruit. By 1954 he was a natural for Inspector Poole, the unnervingly well-informed title character of An Inspector Calls.

Sim was a deeply private man, notoriously refusing autographs as well as interviews, so it's tempting to read too much into his few reported comments such as the quip that his CBE in 1953 was a consolation prize for all the appalling scripts he'd been sent. But there was a definite falling-off in quality towards the decade's end, with neither Left, Right and Centre (1959), School for Scoundrels (1959) nor The Millionairess (1960) breaking new ground. A subsequent ten-year hiatus from the cinema conveyed his views eloquently enough.

Indeed, Sim would never play a truly pivotal big-screen role again, the relative brevity of his appearances in The Ruling Class (1972), Royal Flash (1975) and Escape from the Dark (1977) belying his high-profile credits. He spent most of this period on stage, though he also began to dabble in television, notably a three-year stint as Mr Justice Swallow, whose wry cross-examination and summing-up dominated the second half of each of A.P. Herbert's 'Misleading Cases' (1968-71). A BBC Cold Comfort Farm (1968) saw him as the preacher Amos Starkadder, his trembling, hollow-eyed demeanour suggesting constant fear of unnamed terrors lurking in the woodshed.

In the 1970s Sim played the lead in two television dramas that provided emotionally complex parts of a type he rarely got to perform on the larger screen. In William Trevor's The General's Day he was the retired General Suffolk, eking out a vaguely unsatisfactory existence in a seaside resort and trying to improve matters by replacing his housekeeper Mrs Hinch (Dandy Nichols on splendidly loathsome form) with the virgin spinster Miss Lorrimer. And the year before he died he headlined David Turner's The Prodigal Daughter (1975), where he played the oldest of a trio of Catholic priests forced by circumstance to wrestle with weighty spiritual and moral issues. There's a lovely moment when he reminisces about the life of a dying nun, initially stressing the depth of her faith and the breadth of her learning, but then switching to a cheerful description of her "naughtier moments" and concluding with a beatific "and that is how we must remember her!" With only minor changes, he could have been delivering his own epitaph.