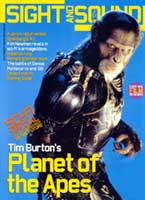

Gorilla Warfare

Tim Burton always wanted to be a big-budget director, but is Planet of the Apes a step too far into the mainstream, asks Andrew O'Hehir

Near the end of Tim Burton's Planet of the Apes the time comes when Captain Leo Davidson, the 21st-century American astronaut played by Mark Wahlberg, must kiss two females goodbye. Davidson has been rescued from almost certain death in the cataclysmic battle between humans and apes by the arrival of an unlikely deus ex machina that's one of the most literal-minded uses of that device in film history. Now he can leave the ape-dominated planet and the distant-future era where he has been stranded and make his way homewards through space and time.

One of his snogging partners is a flaxen-haired beauty played by former model Estella Warren, whose appearance suggests that even though the planet's humans are reduced to primitivism and slavery, they still have access to lipstick, eyebrow pencil and other crucial styling aids. The other is a chimpanzee revolutionary named Ari, played by Helena Bonham Carter with an endearing assortment of twitchy, snuffling, louse-picking simian mannerisms. A member of the ape aristocracy whose father is a moderate leader of the Senate (meaning he stops short of advocating the wholesale extermination of humans), Ari has sided with the cause of human liberation against her own kind, out of principled conviction or a prurient interest in Davidson or both.

Of course we in the audience can see the glamorous actress behind the ape mask; this scene goes nowhere near the taboo territory of Nagisa Oshima's Max mon amour (1986) in which Charlotte Rampling plays a woman who falls in love with an actual chimp. Still, a ripple of something - curiosity or arousal or discomfort - went through the crowd at the Manhattan preview screening I attended. In the event, both kisses are chaste (and the Warren one rather more lingering). So Burton's film remains indecisively suspended between conformity and transgression, even as Wahlberg speeds off towards the requisite surprise ending. (This one is borrowed from the satirical 1963 novel by Pierre Boulle, rather than from Franklin J. Schaffner's landmark 1968 film, which ended so memorably with Charlton Heston weeping beside the Statue of Liberty's ruined torch.)

Like much of Burton's work, Planet of the Apes represents a B-movie aesthetic elevated to the level of mega-budget spectacular and then overloaded with themes, images and references to the point of incoherence. As far as I know, no critic or academic has adequately theorised the process by which a classic genre or exploitation film - Shaft or Planet of the Apes or Invasion of the Body Snatchers (and we'll see about Rollerball) - is remade as a mass entertainment, inflated with a pompous sense of its own significance and loses the edge of anger or cynicism or paranoia that made it powerful in the first place. Burton's Planet of the Apes is superior in every technical respect to Schaffner's, but it's also more cluttered, less self-assured, more diffuse in its impact.

This doesn't look so much like a reconceived version of the Schaffner film as a later and more sumptuous edition of it; the scrambled classical-gothic-Indian-arabesque design of the apes' planet remains intact but is developed to an exquisite extreme. As advertised, Rick Baker's remarkable ape costumes are in a tangible sense the stars of the production, since they allow actors as various as Carter, Tim Roth, Paul Giamatti and Michael Clarke Duncan to create distinctive, almost operatic-scale characters who are decidedly more interesting than the film's humans. There are impressive action sequences and striking tableaux and, in Roth's sneering General Thade - along with Carter's, the film's stand-out performance - a compelling villain whose malevolent intelligence is devoted to learning every destructive lesson the interloper from human civilisation can teach him. In fact, it's the anodyne Davidson, the apparent hero of the film, and not Thade, who is the story's real vector of evil. Perhaps this makes Planet of the Apes more interesting as parable, but correspondingly flatter as drama. Burton never appears interested in Davidson's dilemma, and seemingly abandons Wahlberg to wander around the set gawking at the monkeys. One almost feels the director sees the real story as the struggle between Ari and her ex-lover Thade over the future of ape civilisation, and rather wishes the interfering human - significant mainly as a love object or plot device - would get out of the way.

Indeed, if the 60s and 70s Apes films were documents of racial guilt - as became increasingly obvious the longer the series went on - this one is a document of species guilt. Burton and his screenwriters (William Broyles Jr, Lawrence Konner and Mark D. Rosenthal) offer a jittery catalogue of millennial anxieties, from the hazards of genetic engineering and the corrupting influence of technology to ecological catastrophe and weapons of mass destruction. Davidson tells his group of ape and human renegades that on his planet (i.e., ours) the great apes have been wiped out in the wild and survive only in zoos or scientific breeding programmes like the one aboard his space station. And in case we haven't got the message yet, Burton also provides a portentous cameo by Heston, as Thade's dying father, telling his son that 'no creature is as devious, as violent' as a human being. (There's a gag of sorts underlying this scene: Heston is the real-life president of the principal gun-owners' group in the US, and his character apparently possesses the planet's only firearm.)

Between the film's sermon on human evil, the spectre of forbidden love and Burton's abiding affection for misunderstood outsiders, embodied here in Carter's human-loving chimp, there seem to be numerous opportunities for narrative tension and conflict. Instead the writers largely rehash the plot of the Heston film, and more generally the standard Odyssean saga of an adventurer far from home in a world turned upside down. A cynic might well wonder whether Broyles et al had a recent example in mind: you could describe this Planet of the Apes as a remake of Ridley Scott's Gladiator, with monkey suits as well as centurion armour (not to mention a dose of the Hong Kong-style aerial work belatedly brought to Hollywood's attention by Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon). Like Russell Crowe's Maximus, Davidson is enslaved by those he once commanded and becomes the nemesis of a usurper (Roth's General Thade in place of Joaquin Phoenix's Commodus) who seeks to wrest imperial power away from a dithering Senate. But unlike Maximus, Davidson is more of a vacancy than a commanding presence, and his struggle to return to his own time and place seems petty amid the chaos and intrigue and overwhelming production design around him.

Wahlberg has agreeably played a series of working-class guys thrown into unusual circumstances in such films as Boogie Nights, Three Kings and The Perfect Storm, but he's strikingly ill at ease with the hero's mantle here. Davidson seems alternately repulsed and bewildered by this brave new world and its creatures, and Wahlberg lacks either the stoical, masculine gravitas that made Crowe the undisputed centre of Gladiator or the sheer scenery-chewing histrionics of a Heston or a Kirk Douglas. In fact, it's hard to resist the notion that Burton and the writers have deliberately undercooked the character; we learn nothing about Davidson's life except that he cares about his chimps and that his friends on Earth are having a pool party without him.

We begin in the year 2029, aboard the space station Oberon where Davidson is helping train a race of genetically engineered superchimps to serve as deep-space test pilots. (If you suspect this sinister project might have unintended consequences, well, you're nearly as clever as the film-makers.) When one of his prize specimens disappears with a shuttle craft into some kind of electronic disturbance in space, Davidson defies orders and goes after him. Flung several centuries forwards by the same electro-whatsit, he crash-lands in a jungle lagoon on an unknown planet just as a group of the area's wild humans, led by Kris Kristofferson, are being captured and enslaved by the stronger, more agile apes.

Davidson is a desperately dim character; it appears intellectual standards in the US military haven't trended upwards since 2001. He struggles to understand the planet's social order, asking Warren, who plays Kristofferson's daughter, 'What made these monkeys like this?' Reasonably, she replies, 'How should they be?' It takes him most of the movie to grasp what the audience already knows - that he is far in the future and the crew of the Oberon and everyone he knows on Earth are dead.

As for the fact that everyone on the planet speaks idiomatic English, Davidson neither seems to notice nor acts surprised. The original Planet of the Apes film franchise found an ingenious way of justifying this B-movie convention, of course, since the planet in question turned out to be Earth. (Never mind that the intervening centuries of isolation would have produced a variant of English as distant from our own as Chaucer's was.) Burton's planet is not Earth, although as Davidson laboriously discovers after his escape from captivity and pilgrimage into the desert, there is a historical connection between the two. Still, the fact that the apparent linguistic anachronism is never addressed seems bothersome here in a way it didn't in the earlier films, perhaps because higher production values imply greater attention to detail and less naked allegory.

As Davidson and his fellow prisoners are brought into the ape city in the same rope-lashed wooden carts used to transport Heston, we get a brief, intriguing glimpse of a stratified ape society complete with juvenile delinquents and pot-smoking beatnik musicians. Here Burton strays into the terrain of science fiction as social satire, suggesting George Lucas or Gene Roddenberry (or indeed Rod Serling, co-writer of the first Planet of the Apes) at their most sophisticated. As any fan of the films knows, this society has clear caste hierarchies: chimpanzees like Thade and Ari are the intellectual leadership, warlike gorillas (including Duncan and Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa) provide the muscle, and the buffoonish orangutans focus on business matters. (Giamatti provides a little classic Hollywood comic relief as an orangutan slave trader in the pusillanimous tradition of Bert Lahr's Cowardly Lion: 'One thing you don't want in the house is a human teenager,' he assures a potential customer.)

But the moments when we see what Burton's Planet of the Apes might have been only make clear how formulaic and tedious it largely is. The script creaks audibly during a long, slow early patch when we seem to be waiting for the production to catch up with the audience: apes argue tiresomely about whether humans are predisposed to evil or possess souls; Davidson tiresomely explains that on his planet apes are trained to beg for treats. (This echoes Roddenberry and Serling at their most pedantic.) Worse still are the efforts at waggery: 'Extremism in the defence of apes is no vice,' says one character. 'You can't solve the human problem by throwing money at it,' says another.

When Carter appears as Ari, sniffing at Davidson in distinctly erotic fashion, the movie momentarily seems to find a centre and a direction. He holds a knife to her throat and, like the human heroines of entirely too many films, she loves him more for it. But Burton and the writers lack the courage or the foolhardiness to push this interspecies romance too far (even sci-fi bestiality would surely spark Christian boycotters in several US states) and it gets shuffled to the margins of the story. Pursued by Thade, the would-be Prometheus who wants to learn whatever he can about human technology before killing Davidson, the renegade non-couple head out for the territories along with Warren, a few other human escapees and a gorilla warrior turned peacenik (Tagawa).

Planet of the Apes, like most of Burton's films, is full of grandiose imagery that grows wearying before it ought to, perhaps because the elaborate production design and unstable mélange of film-making styles seem unconnected to any sense of narrative necessity or economy. As always, some scenes are worth watching on any terms, including the striking night-time battle sequence on a riverbank plane studded with illuminated tents, which recalls the Kurosawa of Ran (1985), and a final confrontation between apes and humans in the desert that seems closer to the grand set-pieces of David Lean. There are also faint but plausible echoes of Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, along with a dunderheaded rehash of Henry V's St Crispin's Day address to his troops. ('Our history is full of men who did incredible things,' Davidson tells his ragtag band of brothers. 'Sometimes even a small group can make a difference.')

In contrast with the brutal, wordless simplicity of the Schaffner film's conclusion, this movie has numerous puzzles to work out in its last few scenes, with mixed results. What is the significance of Simos, the Shiva-like ape deity to whom superstitious gorillas pray? What are the sacred ruins of Calima, where Davidson's homing beacon leads him? Why does the arrival of Davidson's missing chimp in its spacecraft make all the apes forget about killing the humans? What sense are we to make of the transformed 21st-century Earth to which Davidson finally returns? (I think I have figured this out, though it took me several days.) And is there anyone or anything in the whole movie we care about besides Ari, the class traitor who has been branded as a human and a slave and then abandoned by the man she loves?

It's nothing new for a Burton film to be a magnificent edifice of design, a great work of adolescent imagination built around an inconsequential narrative and a hollow central character. As one critic observed on the release of Batman in 1989, the title character was three-quarters Batsuit and one-quarter Michael Keaton (which may have been a generous analysis). But at least Batman's alter ego, oddball millionaire Bruce Wayne, like Johnny Depp's dotty detective in Sleepy Hollow (1999) recognisably belonged to the Ed Wood-Edward Scissorhands family of eccentric loners who engage Burton's instinctive sympathy. Planet of the Apes is less whimsical than Mars Attacks! (1996) but it has some of the same pointless, miscellaneous quality and a similar sense that the director may be half-consciously sabotaging his own work.

On one hand it's ludicrous to suggest that Burton is a victim of his own success, since becoming a big-budget Hollywood director was the only thing he ever wanted. Perhaps that's the problem; big-budget Hollywood directors don't have the autonomy they used to, unless their name is Lucas or Spielberg. Burton, one might propose, longed to bring the aesthetic of cult horror and sci-fi fandom to a mass audience, in much the same way as Douglas Sirk once did with romance and melodrama. He wasn't alone in this; David Cronenberg and Paul Verhoeven, to cite the obvious examples, parlayed their hip outsider status into lucrative Hollywood projects that stretched the boundaries of mainstream sci-fi. But that window of opportunity seems to have closed, and both those film-makers have had to choose between diverging paths. Hollow Man was standard-issue Hollywood action adventure, easily the most conventional film of Verhoeven's career, while Cronenberg (voluntarily or not) has returned to low-budget Canadian obscurity.

In the era of the global mass audience and CGI effects, mainstream cinema - or at least spectacle cinema - is becoming an increasingly conservative and almost anti-narrative form. This is the kind of pronouncement elitist critics conventionally make, but such summer hits as Pearl Harbor or The Mummy Returns or Lara Croft Tomb Raider make no pretence of offering plot or character beyond a set of reassuring poses and gestures, as familiar as the stock figures of grand guignol were in an earlier day. Stories and characters that don't fit this pseudo-heroic spectacle model are now primarily the province of television, or of the worldwide independent cinema that has accepted its marginal niche and now seems to be thriving; call it the democratic flipside of globalisation and digital technology.

There are, of course, other former independent film-makers who have successfully adapted themselves to Hollywood. Steven Soderbergh is viewed, with some justification, as the reigning prince of mainstream drama, while Gus Van Sant appears to have suppressed every impulse that once made him seem dangerous. But no one wants or expects Burton to make heartwarming, realistic drama. He is supposed to deliver mock-gothic teenage darkness, the flavour of outsiderness and eccentricity without, so to speak, any of the calories.

It would be difficult, and perhaps impossible, for a film-maker of Burton's status to make a reversed-polarities version of Planet of the Apes that embraced the damaged and alienated Ari as its heroine (and no truly independent director would get the chance in the first place). So he accommodates himself more or less uncomfortably to his material, squeezing characters or elements that engage his attention into the corners when he can. It may be unfair to blame the Hollywood system, rather than Burton himself, for his predicament. His own shallowness and cavalier attitude towards story are at least partly responsible for turning him into a hired hand almost indistinguishable from Barry Sonnenfeld, an artificer who wraps formula in the trappings of cool. At any rate, he doesn't seem happy about it. Is there a way back to Tim Burton's home planet from here, and does it still exist?