Primary navigation

Robert Bresson's films are so singular an achievement they have inspired legions of fine directors. Here Olivier Assayas, Bruno Dumont, Paul Schrader, Eugène Green and Aki Kaurismäki pledge their allegiance, while Michael Brooke introduces his work

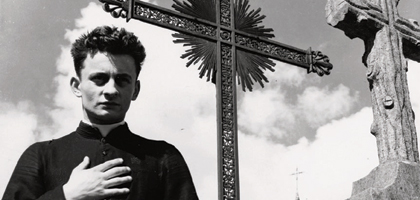

Robert Bresson was born in either 1901 or 1907, a discrepancy never fully resolved, though his death in 1999 led many to favour the neatly century-spanning option. He initially trained as a painter, a discipline that left him with an acute awareness of the need "not to make beautiful images but necessary ones." (The first irony of Bresson's cinema is that his films, while in no way abandoning that precept, are often rapturously beautiful.)

Switching to cinema, he spent the 1930s finding his feet. His first film was the slapstick farce Les Affaires publiques (1934), which he described as "like Buster Keaton, only much worse", though in fact it's a competent, often funny piece. He also worked on films as writer or assistant director.

In the early 1940s he spent a year as a German POW, an experience that fuelled many episodes of literal or psychological incarceration in his films. This is apparent in his first feature Les Anges du péché (1943), set in a Dominican convent founded to provide moral guidance to women recently released from prison. Its occasionally melodramatic content notwithstanding, the film's abiding atmosphere of calm severity is quite unlike the work of most debutants.

The brittle, scintillating Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne (1945) was the end of a line: its formal elegance, Cocteau-scripted wit and overt theatricality would become anathema to Bresson, who spent the years following its commercial failure devising an approach to cinema closer to music and painting than to theatre and photography, eschewing professional writers and actors in favour of 'models' delivering their lines in a pallid monotone, often in voiceover. Irony number two is that many of these 'models', certainly including the donkey Balthazar, give performances as emotionally wrenching as any great classical tragedian.

Six years passed before the first true Bresson film Diary of a Country Priest (1951), and another five before A Man Escaped (1956), these gaps the inevitable price to pay for what was already one of the most uncompromising bodies of work in cinema. But they were both masterpieces, as was Pickpocket (1959), each creating profound spiritual meditations from themes of a young priest struggling with his faith, a real-life escape from a Nazi prison, and a search for redemption via petty theft respectively. Irony number three: despite no apparent interest in narrative surprise, these films rival Hitchcock or Clouzot for palm-sweating suspense.

The 1960s were more problematic, with Trial of Joan of Arc (1962) and Une femme douce (1969) less sure-footed than before. But they bookended two of Bresson's finest films, Au hasard Balthazar (1966) and Mouchette (1966), both examining the grim lives of the downtrodden and marginalised, whether a donkey or an impoverished teenage girl. After the minor but touching oddity Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971), Bresson made Lancelot du Lac (1974), a typically unflinching look under the stone of the Arthurian mythos. Equally blunt was The Devil, Probably (1977), a student's howl of despair against the modern era's iniquities - it was banned to under-18s in France following claims that it incited suicide (though this is a recurring theme in Bresson). And finally, another masterpiece in L'Argent (1983), a Tolstoy adaptation illustrating how a seemingly trivial transaction involving a forged banknote leads inexorably to mass murder. It was widely perceived at the time to be Bresson's swansong, though he made one final attempt at mounting his dream project Genesis before a lengthy retirement.

What is Bresson's significance for you?

OA: I wouldn't be the same person now if I hadn't seen Bresson's films - but that's something a few French directors could say. I first caught them on TV when I was a teenager and they felt so different, so beyond anything I'd witnessed on film. I reacted to them on such a deep poetic level that it gave weight to the idea that one day I would make films myself. It's through Bresson that I discovered movies could go that far.

Bresson's films aren't just spiritual experiences, they're very physical, very concise. They don't have the kind of slowness and complacency that a lot of Bresson disciples have picked up on and completely misunderstood. The sharpness of his eye and the daring notion of going into areas where cinema had not been before are unique. His films give you the feeling, especially when you're a teenager, that you can dedicate your life to art.

What is your favourite Bresson film and why?

OA: I've had various Bresson favourites at different stages of my life. The two films that impressed me initially were A Man Escaped and Pickpocket, then two movies I related to later were The Devil, Probably and L'Argent. I saw The Devil, Probably when I was 17, which is the same age as the lead character; I can't say I liked it and I remember thinking, 'What is he talking about?' Then ten years later I realised that I had been exactly that character, it was my world, but I didn't grasp it at the time because it was too close to me.

What, if anything, have you borrowed from Bresson's cinema?

OA: When I was making my early films, Bresson was influential in the sense that I would spend a lot of time thinking about designing the shots and how the actors should be. My actors have never been 'Bressonian', but I'm minimal in my writing, not seeking superficial emotion but having inner emotions that come through without being overstated.

To me the influence of a great film-maker like Bresson is more about giving you the notion that you can define your own path and hope to go as far as he did. In any case, the whole idea of direct quotation is something I'm suspicious of. But in my first feature Désordre there's a scene where a teenager steals money from the drawer of his doctor father and I don't know if it was a quote or a subconscious quote, but there's a very similar shot in L'Argent. Even when I was making my fourth feature Une nouvelle vie and had to choose an actress for the teenage lead I remember thinking, 'Which girl would Bresson have picked?' And I knew he would have wanted to work with Sophie Aubry. Then when I made my next film L'Eau froide and subsequently watched Bresson's Mouchette I thought, 'Oh my god, I was influenced by a movie I'd never seen.' That says a lot about how important Bresson is to me.

What do you see as Bresson's true legacy?

OA: Bresson touched something very close to the bone of what French cinema is about; ultimately he defined it. Screenwriter and director Alain Cavalier said that in French cinema you have a father and a mother: the father is Bresson and the mother is Renoir, with Bresson representing the strictness of the law and Renoir warmth and generosity. All the better French cinema has and will have to connect to Bresson in some way.

They showed a series of his films in Beijing about seven years ago and now you get pirate Bresson DVDs all over the place. His work is just so close to the soul of what cinema is that in any film culture you will have people who respond to him. Like Tarkovsky, he's one of the great artists of the 20th century, in any medium. They are the two great poets of cinema: every one of their films is essential and they haven't made anything remotely mediocre. These are movies outside of time and space - and you feel their whole lives depended on making them.

What is Bresson's significance for you?

BD: Bresson brings an original and permanent voice to cinema as an art, which is something that has largely disappeared today. His masterful direction and mise en scène show us how we can use the medium to tell a story that's both moving and rigorous. His films are wholly cinematic - not just the throwing together of illustrations for a piece of literature - and his shots are quite astonishing. He uses close-ups in a way that's very strong and that leads us, as viewers, to reflect on what we see.

Another thing I admire is his direction of actors: this element in his films that seems blank or neutral but in fact involves a great deal of artifice. The way he works with his actors, and recounts the story through their eyes, is achieved by demanding and authoritative processes that result in a lesson in how to be exacting, how to make cinema with limited means.

My own desire to make films came from Walt Disney, but what I found in Bresson is a form of cinema that's austere and sombre, that makes us look inside ourselves and examine our own lives, that has a philosophical dimension which is no longer present in the general entertainments of cinema. It has the same heightened style and grandeur you find in great tragedy.

What is your favourite Bresson film and why?

BD: Diary of a Country Priest is a film that overwhelms me each time I see it. It has a spiritual vein that touches me very deeply; it's a film that results in grace. It's all crafted to take us to that final shot, which is absolutely extraordinary. That, for me, is cinema: how to lead, shot by shot, to an end result that's totally strong.

What, if anything, have you borrowed from Bresson's cinema?

BD: I don't think of Bresson in terms of my own cinema - I feel closer to Rossellini, Kubrick or Bergman. It's true that we share a desire for spirituality: you find it in the way Bresson films, in the way he sets up his camera, which is very respectful and I hope is something I have too. But otherwise our methods are very different - for instance, I work mostly with direct sound, which Bresson never did.

You don't set out to imitate someone: you look instead for a spirit that inspires you to find your own voice. But everyone has an apprenticeship - look at Van Gogh, who began by imitating Millet before he forged his own style. And I'm not joking when I say I want to make films that are popular; I have no desire to hide in the margins. I believe you can make films that are popular and rigorous, that have a dignity to them.

What do you see as Bresson's true legacy?

BD: Critics struggle to find analogies with Bresson each time a film-maker does something vaguely similar. But Bresson carved out his own path and it would be foolish simply to follow in his footsteps. He broke away from the theatrical tradition of cinema to create films where the sound is quite extraordinary - if you look at Jacques Tati you'll find the same thing, though he's concerned with comedy not tragedy.

As for Bresson's legacy, Maurice Pialat was greatly influenced by him, but he became Pialat. And Bresson himself was certainly influenced by Dreyer when he began. There's that continuity in cinema: we're all part of the same story.

Interview and translation by Paul Ryan

What is Bresson's significance for you?

PS: My view of him is very theoretical but also very personal. I saw Pickpocket in 1969 when I was reviewing it for the LA free press: I was so knocked out that I reviewed it two weeks running. And what I saw, beyond what I wrote about, was the kind of film I could make.

I'd come from a very illogically driven religious background, a seminary, and then I'd fallen into the Los Angeles counterculture of 1968. I thought there was no middle ground - that where I came from and where I'd arrived were irrevocably separate. Yet when I watched this film, which was part of European art cinema but also from the world I'd come from, I realised those two worlds were not so far apart. I saw a meditation about a man and his room, about solitude and spirituality, and I recognised that there was a meeting place between past and present. I also realised that there might be a place for me in film-making: I'd thought I was a critic and that was where I belonged; I thought I couldn't make a film about a man and his room.

Three years later I wrote Taxi Driver, which is that film with a lot of anger in it. It's not meditative or transcendental, but it came from Pickpocket. So from one Bresson film came my book Transcendental Style in Film - Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer - and Taxi Driver itself, which arose from the incentive and justification to create that Pickpocket gave me.

What is your favourite Bresson film and why?

PS: My favourite Bresson films are the prison cycle: Diary of a Country Priest, Pickpocket, A Man Escaped. Then he moves the metaphor a bit and you get Trial of Joan of Arc. Then he moves it a little further and you get Mouchette, which is about a young woman. Then in Au hasard Balthazar he gives the donkey the country-priest treatment - and the audacity of that is quite astounding.

What, if anything, have you borrowed from Bresson's cinema?

PS: The last line of American Gigolo is the last line of Pickpocket. And there's a scene in my new film The Walker that's very much like a visual from the same film. Then in Taxi Driver Scorsese and myself always referred to our making the gun glide by Travis Bickle as 'the Pickpocket scene'. But in terms of his acting style Bresson breathed such rarefied air that most of us would be asphyxiated in it.

What do you see as Bresson's true legacy?

PS: Even if people aren't directly influenced by Bresson, it's important that you can make a film with his kind of aestheticism. The very fact that you can do it runs against what many of us think cinema is - if cinema is kinetic, about action and empathy, then the two things Bresson eschews are action and empathy.

He is the most singular of artists. Every so often someone tries to do a Bressonian film - you could say that Béla Tarr or Angelopoulos or Sokurov are in that tradition, but their films are more about quietude than what Bresson was doing. He's like a light, way, way up in the distance: it's very exciting to know the light is still on, but you're never going to get there.

What is Bresson's significance for you?

EG: Bresson is the film-maker who most thoroughly explored the nature of cinema, identifying what is specific to cinema and to no other form of artistic expression. He's the director who made me think about what film is when I was 19 years old and saw Diary of a Country Priest in the Bleecker Street Cinema in New York. I didn't know who Bresson was - I had a ticket for three films and his was the last. I don't even remember what the other two were.

When I came to France I watched his films many times. Then since I started making films myself I've had a great deal of time to think about what I want to do, and Bresson has played a key role in that gestation, in my becoming a film-maker.

What is your favourite Bresson film and why?

EG: I think the two Bresson films that touch me most today are Au hasard Balthazar and The Devil, Probably, in which I played an extra in a crowd scene. When I first saw it I thought it didn't really express what it was like to be young at that time, but now I think it captures that reality perfectly.

What, if anything, have you borrowed from Bresson's cinema?

EG: Stylistically I didn't borrow much from Bresson's cinema - it's more the concept that the essence of cinema is to make the spirit apparent through an exploration of matter. That's a very strong tie I have with him: he's a director who expresses spiritual things.

What do you see as Bresson's true legacy?

EG: Most serious film-makers nowadays have a great deal of respect for Bresson, which wasn't the case when he was alive. I used to go to screenings first thing in the morning when there were very few people there because if you went in the evenings there was a lot of noise - people making fun of the actors' lines. Today as soon as there's a film that's rather austere people say it's Bressonian, but I don't think that's the case. The most important thing is his spiritual legacy.

Someone said to me recently that he's a director for adolescents, but I don't agree. For me he expresses some things that are in the nature of adolescence, which I share with him, and of course almost all his characters are young. But I think you can appreciate Bresson at any age.

I wouldn't say he progressed as a film-maker: his last film L'Argent is his most desperate and the one I've watched least. He's one of those directors in whose work you can detect a certain evolution, but he also has something essential that remained from his first film to his last.

What is Bresson's significance for you?

AK: I admire his unique rhythm in editing, his habit of leaving the picture 'empty' now and then before the cut.

What is your favourite Bresson film and why?

AK: Au hasard Balthazar: it's always more touching and brightening to follow a donkey than a man.

What, if anything, have you borrowed from Bresson's cinema?

AK: I imitated his style partly openly in my childish way in The Match Factory Girl in 1989.

What do you see as Bresson's true legacy?

AK: No mercy for mankind when it is not deserved - in other words, never.