Return Of The Cool

Nick James talks to Bruce Weber about his stylish 1988 portrait of Chet Baker

For anyone who was a culturally aware British youth in the 1980s, the name Bruce Weber equates with a set of hipster ideas about beauty and style - largely homoerotic, for sure, yet also bound up in the post-New Romantic club culture of 50s retro and haunted cheekbones that transcended sexual preferences. The US photographer's fame in his home nation was achieved later with Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren ads featuring the return of 50s-style V-shaped beefcake torsos - anathema to punks - but over here his earlier career was filtered through The Face and myriad European men's fashion mags.

Part of his work's charm was the way he'd mix old images of favourite icons in with his new shots, often scrawling celebratory dedications to friends on them with winning jollity. This health-and-happiness idyll soon became a poignant counterpoint to the HIV plague.

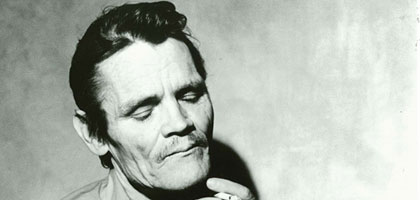

One thing that might have united all the 80s hipster constituencies, though, was Weber's 1988 film about jazz trumpeter Chet Baker, Let's Get Lost. Baker was still around, a ravaged survivor of years of heroin use and road living, with a tangle of relationships with women trailing after, most of which involved women giving, Chet taking. Weber's film of him, though, is all affectionate impressionism, finding a loose monochrome groovy feel in which Chet sings (heartbreakingly in a husky version of his former boyish intonation) or indulges in fractured reverie, simultaneously evoking cool distance and searing melancholy. Meanwhile, his lovers report glimpses of his meaner side.

Nick James: Were you always a Chet Baker fan?

Bruce Weber: I had a huge record collection when I was growing up in western Pennsylvania. I was not only infatuated with the music but also the art and design. My dad was a big jazz fan so I looked to music as a way to see things.

NJ: And when did you first set eyes on Chet?

BW: I was at boarding school when I got this great album Let's Get Lost and Other Songs and I was looking at all these William Claxton pictures and I just loved how the album cover looked. Much later on, I wanted to photograph Chet but I couldn't find him. And then I was in New York in a snowstorm and this convertible pulled up with the hood down. I said, Oh my god that's Chet Baker. He was in a tweed sports coat and looking amazing. I wish I'd had my camera with me.

NJ: What were your inspirations for the film?

BW: I wanted to make a short film from an Oscar Levant song called 'Blame It on My Youth'. I went in to record it with Chet. I thought it would be a six-minute film about him, but we had such a good time together and his life started opening up to me. You know how you're at a bar and you meet somebody that you wanted to talk to but were kind of shy - it was like that. There's a real reciprocal thing in making a film. You choose somebody you can live with for a while because you're going to be dealing with that person the rest of your life.

NJ: Did you have the kind of set-up where you could respond to things quickly?

BW: We didn't have a lot of money. [Cinematographer] Jeff Preiss had a little Aaton and a Bolex and I had a Bolex. The first Bolex I ever got I got in London. This man came over - like a guy who played rugby - and he said, "I'll tell you if got a shot or not". He said, "If you have a shot that lasts for 'One grasshopper, two grasshoppers, three grasshoppers' you've got a shot." I started doing it out on the street. My friends were asking, "What are you saying?" But when I was doing Chet's film sometimes we only had one grasshopper.

NJ: It turned into a biographical film. Were there other biographical films that you had in mind or looked at?

BW: We dove into it directly after making Broken Noses, which a lot of people disliked because of the technique that we used. I look back on these films as a big part of my youth and all the things that people disliked I really like because we were taking chances and not worrying about what people were going to write. We started films the same way I do photographs. I was taking pictures throughout Let's Get Lost because it's a way for me to find my place. My influences are very different from what you see in my films. I'm a really big John Ford fan. And probably my second favourite film is Lindsay Anderson's This Sporting Life.

NJ: The rugby connection again.

BW: Chet could look like he had played rugby as a boy and then got messed up. In America there's a lot more pretty boys who play rugby than there are in England.

NJ: It is very much evocative of the time, not only in looking back at the 50s and 60s. It also has a vital sense of the 80s.

BW: My sister and I grew up in the Midwest and she was very involved in the music business. She worked for a lot of rock groups and with David Bowie for many years. So I was always involved with a lot of musicians. I met a lot of men who I became fond of just as friends because they were older and I admired them. When we had the blackout in New York my sister was working with Iggy Pop and the idea of walking around New York with Iggy Pop was an experience of the kind I've tried to put into my films.

NJ: Many of Chet's women tell us how deceitful he was. How were you able to plot your own line of truth?

BW: We just never new what was true and what wasn't. That's why I can relate it to walking around the streets of blacked-out New York with Iggy Pop.