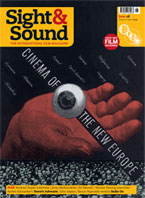

Cinema Of The New Europe: Lest We Forget

After years of neglect in the West, Andrzej Wajda, father figure of Polish cinema, is back with 'Katyn', the latest of his unflinching examinations of his country's tragic past. Interview by Michael Brooke and Kamila Kuc

Andrzej Wajda used to appear regularly in the pages of Sight & Sound, from the 1950s, when his trilogy of films about World War II and its aftermath made his - and Polish cinema's - international reputation, to the early 1980s, when the world's attention was focused on Poland's Solidarity-sparked political upheavals. Since then he has largely been forgotten here, and his films have dropped off the radar of British distribution. The last Wajda film to open here was his 1990 portrait of a wartime Jewish doctor, Korczak, and despite his stature as one of European cinema's giants, UK DVD labels have shown scant interest in his back catalogue of over 30 features. May's BFI Southbank retrospective offers a chance to catch up with 13 key titles, following the British premiere of his latest film Katyn.

Katyn is the first Polish film to tackle two of the most contentious issues in the country's history: the massacre of up to 20,000 members of Poland's intellectual and military elite and its cover-up by its Soviet perpetrators. Wajda's own father was a victim of the massacre, but it was impossible for the director even to consider the project until Mikhail Gorbachev acknowledged Soviet culpability in 1990. On its release in Poland last year, the film's impact was enormous: it became a box-office hit (beaten only by Shrek the Third) and - to Wajda's disgust - a nationalist political football during the recent election. It was also shown to every serving member of the armed forces as a reminder of what their predecessors died defending.

If Katyn is ultimately good rather than great Wajda, its cultural and historical importance is already assured. It marks the latest entry in a complex cinematic dialogue with Polish history that Wajda has been conducting for over half a century.

Sight & Sound: In Britain your first three films 'A Generation' (1954), 'Kanal' (1957) and 'Ashes and Diamonds' (1958) are by far the easiest to see. Do you think that too much attention is paid to your early career?

Andrzej Wajda: I owe my first international success to Lindsay Anderson's review of A Generation. This meant that the newly established Polish Film School was carefully monitored in the West. When asked, "What is behind the Berlin Wall?", the Polish directors of the 1950s gave the truest answers of anyone in the Eastern Bloc. Now I stand alone. There is no wall and nobody behind me. Besides, it was half a century ago.

S&S: Some film-makers, notably Alain Resnais and Marguerite Duras, have claimed that to dramatise wartime tragedies such as the Holocaust is to try to represent the unrepresentable. Since a number of your films evoke World War II in a vivid way, how do you approach this issue of representation?

AW: It has more to do with the fact that those artists, who are sensitive to moral issues, are afraid that such tragic events, if made accessible enough, might be exploited as 'good film subjects'. I do not agree with them. I survived the war. I know what fear, sudden death and poverty are. Why should I not tell others about it? Especially since I have never been tempted by the delusion of a large, international audience.

S&S: Which comes first: the evocation of a historical epoch, or the characters and narrative within that epoch?

AW: I always begin with human fate. This is what truly interests the viewer. If the characters are already alive in the script, I begin thinking about how to represent an appropriate historical background. Sometimes the background establishes the film's originality. Kanal is a good example. The fact that most of the action took place underground, in sewers with no way out, reflected the essence of the Warsaw Uprising [against the Nazis], which was destined to fail from its first day.

The situation was different with Man of Iron (1981). There, I was fully aware that my film could take an unprecedented part in historical events caused by Solidarity. I decided to make this film without a script, but I already had well-drawn characters from Man of Marble (1977). Having characters with a past, I knew exactly how Maciej [played by Jerzy Radziwilowicz] and Agnieszka [Krystyna Janda] would behave during the shipyard strike.

S&S: Samuel Beckett's 'Watt' ends with the line, "No symbols where none intended." Do you ever feel like saying a similar thing before the credits of your films or do you enjoy seeing critics read messages into them?

AW: Symbolism and censorship - these two words represent the Polish Film School's problem well. How to communicate with the audience behind the censor's back? To answer this one needs to know that censorship, in the first instance, relates to words - because each ideology is expressed in words, whether it's "Our Father" or "Existence precedes essence". Censorship does not permit the transformation of, or any allusion to, the basis of the socio-political establishment that this censorship wishes to protect. But are images equally explicit for different viewers? Do they mean the same to everybody? After all, pictures from the Bible are the artist's fantasy, not a Bible, so...

The image is cinema's essential element and its international language, thus there is nothing strange about the fact that the Polish Film School used symbols - sometimes only national ones, but occasionally ones comprehensible to the rest of the world too. At the end of Ashes and Diamonds, the death of Maciek Chelmnicki [played by Zbigniew Cybulski] on the rubbish tip was a successful association, as many in Poland spoke of the 'garbage of history'. But for those who did not understand socio-political changes in Poland it was also a slap in the face as Maciek was the film's hero.

A certain level of limitation in comprehending national cinema is unavoidable. The question is whether these films still allow the viewer to understand the director's efforts. When I asked Akira Kurosawa how he managed to interpret Shakespeare's Macbeth so deeply and accurately he answered, "Mr Wajda, I had a classical education in Tokyo." Bergman and Fellini had a similar background, as did many of their viewers. And perhaps this is the reason why European cinema managed to build its own community so successfully. Nowadays schools do not teach the same values, hence their education is not called classical.

S&S: On a number of occasions you have mentioned that there were two types of censorship in Poland: the external, enforced by the authorities, and the internal, imposed by the film-makers themselves.

AW: Internal censorship is created by a consciousness of your surroundings. The director cannot play dumb. The script of Man of Marble had to wait 12 years to be realised and its premiere in Poland was still very problematic. It is worth mentioning that the minister responsible for all these problems lost his job while I continued making films. That film would simply not have been made if the script had been written in a moment of hope, without self-censorship. In totalitarian countries censorship is necessary because of the need to falsify the past - and Katyn is also about this kind of lie.

S&S: Though your international fame began early, most of your films - with the notable exception of 'Danton' (1982) - have been made in Poland, in Polish, on Polish subjects, and some require substantial background knowledge to be fully appreciated. Would it be fair to say that your intended audience has always been primarily Polish and that, if your films do well internationally, it is merely a welcome bonus?

AW: I want to speak to everybody and to be understood everywhere. But a long time ago Goethe stated that whoever wants to understand der Dichter, the poet, must visit his land.

S&S: Traditionally Polish painting, literature and film have always been socially and politically engaged, to satisfy a perceived hunger for art that makes sense of a fragmented national history. Do you think that today's international audience lacks that interest in history?

AW: I would say that the absence of my films from British screens is undoubtedly my fault. Shortly after Poland gained political freedom I made a few films from old scripts, which were previously restricted by censorship. Unfortunately it turned out that people in Poland were not interested in them, so I turned to more classical themes. Seven million Polish viewers watched Pan Tadeusz (1999), based on the 19th-century national poem, but the film was invisible elsewhere. It is not easy to be an old director, especially one with a long past.

S&S: In a 1985 'Sight & Sound' interview, you praised American cinema as an example of a truly popular art form, even though it was destroying European cinema. Do you think European film-makers have learned any lessons in the past two decades, or will Hollywood always hold the upper hand?

AW: I am going to say something very original now. While Americans watched our films closely and saw the essence of cinema in them - they made great use of European styles of film-making - we European directors never learned the American lesson of how to tell stories in a cinematic way so the viewer laughs and cries at our bidding. Many years ago, I visited Scorsese in his New York office. He told me that when he started making Taxi Driver he showed his crew Ashes and Diamonds. In Poland we know the films of American cinema masters very well and what comes out of this? Not much.

S&S: Throughout your work there's a recurring concern with presenting the viewpoint of the younger generation, however naive and ill-informed - the romantic idealists played by Zbigniew Cybulski in 'Ashes and Diamonds' and Krystyna Janda in 'Man of Marble' being good examples. Do these characterisations reflect the way you saw yourself as a young man?

AW: It is more about the actors who made those films with me, and who then became conscious citizens of this country. Krystyna Janda, for example, opened the first completely private theatre in Warsaw, where she realises her own project - a concept of social theatre. Jerzy Radziwilowicz has been supporting political protests as a 'man of iron' for many years now.

S&S: Obviously it was impossible to make 'Katyn' before the early 1990s - but why did you wait another decade and a half to begin such an overwhelmingly personal project? Were you afraid it would be seen as anti-Russian?

AW: I am old now and I am not afraid of anything, even the reaction of the Russian establishment. But I would not want my film to be used by any of the sides of this artificially fabricated conflict. I have had Russian friends my whole life, and they shared my point of view: Andrei Tarkovsky, Grigori Chukhrai, Andrei Konchalovsky, Mikhail Romm, Kira Muratova, Alexander Sokurov and many others created their films in much more difficult conditions than mine. I still have many Russian friends, who read my film correctly as standing against Stalin and the communist system.

S&S: You have said that one of your main motivations for making 'Katyn', like Steven Spielberg's for making 'Schindler's List', was to counter widespread ignorance about the historical events, especially among young people. Given your personal connection with this story, were you worried that too much emotional involvement would prevent you from presenting events objectively?

AW: It's true that a contemptuous animosity towards the past is a shabby by-product of Poland joining Europe. But I am not worried that personal feelings of sorrow and injustice might detract from the sharpness of my perception. The script of Katyn is based almost entirely on materials from diaries and memoirs, which capture those events almost in still images. Whether young people like it, I don't know. But it would have been difficult to make this film exclusively for them and completely to their taste. I rely on popular actors creating touching and believable characters.

S&S: Compared to your generation - one "of sons who have to recount the fate of their fathers, for the dead cannot speak" - you have said that young Polish directors don't really know what they want to talk about.

AW: I was undoubtedly too strict in my judgement, as their current situation is certainly more difficult and challenging than ours. But their main task, whether they like it or not, is to defend Poland from descending into parochial nationalism and religious narrow-mindedness. If they do not do this, Polish provincialism will overwhelm their artistic ambitions.