Dream Tickets

The once hugely popular double bill saw unlikely pairings throwing new light upon one another. Now a selection of experts pick their perfect twosomes that are more than the sum of their parts. Introduction by Jane Giles

Who killed the double bill? And when did our days or nights become so short that the very idea of going to the cinema to watch four to six hours of brilliantly compatible or creatively contrasting content became impossible? It's hard to believe but the double bill really did exist, both as a commercial tradition that yielded mixed results (at best jarring, at worst tedious) and as a curatorial ambition to take audiences on a sublime cinematic journey to the end of the night… or at least until 10.50pm.

Once, all cinemas ran a second feature plus a full supporting programme of newsreels, public information films, trailers and ads. Warming up the audience before the main attraction, the B-movie slot was often for 'quota quickies' - lower-budget productions that kept the national industry turning over, creating employment and allowing experimentation. As cinema-going declined after World War II the industry adapted to survive by transforming large dilapidated cinemas into smaller multiplex auditoriums. With fewer seats to profit from, cinemas axed double bills to accommodate three shows a night of the main film, and B-movie production shrivelled.

But non-chain single-screen cinemas stuck to their double bills, providing good value for money, even if the seats were a little shabby. In the 1980s, the London film scene was full of choice thanks to half a dozen repertory cinemas. The difference between the Hampstead Everyman and, say, the Scala in King's Cross was to do with a generational and cultural division of purpose. The Electric in Notting Hill, the Ritzy in Brixton, the Rio in Dalston and the Riverside in Hammersmith each had their own shades of personality.

The Everyman - "London's oldest repertory cinema"(it will be 75 in December) - brought film-society programming to the public. Renowned for its seasons and double bills of American classics or masters of European cinema, the cinema's artful, admirable curation indulged a depth of intellectual experience, championing directors such as Bresson, Fellini, Bergman, Buñuel and René Clair.

The Scala - "London's coldest repertory cinema"aka "the Sodom Odeon"- had a different remit. Back in the late 1970s, Stephen Woolley had overturned a subterranean West End cinema with an American calendar-house-style programme of double bills and foreign-language arthouse movies which tended towards the excesses of Marco Ferreri and Werner Herzog, with a steady devotion to the Surrealists. The staff were young, the art-school audience was driven by music and visual experimentation, and the Pacman machine in the foyer was as much a revelation as Joy Division on the PA between shows. There was no doubt that the films of Scala patron saint John Waters bridged the gap between Fassbinder and Teenagers From Outer Space (1959). The choice was wide, yet audiences voted with their feet and the repeated double bills tended further towards the explicit and extreme.

In 1981 the Scala moved to the former King's Cross Gaumont, the circle area of a 1920s picture palace, with a vertiginous rake, enormous nicotine-stained screen, 'improved' double mono sound, marble mosaic floor, the rumblings of London Underground's Northern Line deep below, men moving through the back rows and a pair of resident cats. The cinema's first double bill in its new premises was King Kong (Merian C. Cooper, 1933) + Mighty Joe Young (Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1949), a tribute to the building's brief incarnation as a primatarium. The cinema's extraordinary atmosphere affected the audience profoundly, acting on their senses in a way that is hard to imagine in more mundane or domestic environments. The intensity of the double bill experience was about being taken through an entire (and probably testing) narrative and still wanting to start again. It seemed normal for several hundred viewers to watch Pasolini's 'Trilogy of Life' (1971-1974) chronologically every other month, and I was genuinely surprised to find a tearful patron traumatised by the six-hour experience of watching W.R. Mysteries of the Organism (Dusan Makavejev, 1971) + Vilot Sjöman's I am Curious Yellow (1967) + I am Curious Blue (1968).

Despite the obvious emphases on director, genre or star, there were no hard and fast programming rules to what made a good double bill - it just had to feel right. Though always at the mercy of rights and print availability, the double bill of the 1980s and 1990s was not shackled to the output of a single distributor, but was in the hands of real enthusiasts, fired up by audiences who crammed the suggestion box with their dream double bills.

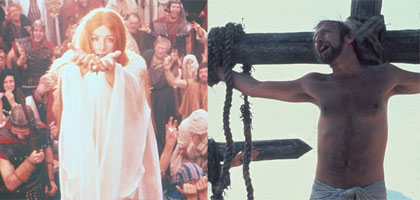

Each bill at the Scala had its own flavour and belonged to a particular day of the week. Mondays were blue, Wednesdays were cult, Sundays were classic. Every Easter we showed Monty Python's Life of Brian (Terry Jones, 1979) doubled with anything from Whistle Down the Wind (Bryan Forbes, 1961), to The Last Temptation of Christ (Martin Scorsese, 1988) to The Devils (Ken Russell, 1971). Every 23 December the Scala showed Wings of Desire (Wim Wenders, 1987) + It's a Wonderful Life (Frank Capra, 1947) before the darkest three nights of the year, but by 27 December was right back to it with Salo (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975) + Pigsty (Pasolini again, 1969) or Salon Kitty (Tinto Brass, 1976). The 11pm to 7am all-night Saturday shows evolved from classic froth (Marilyn Monroe, Bogart, the Marx Brothers) to modern schlock (Arnie), via the ambitious (Cocteau), raucous (Blaxploitation, Steve Martin, anything gay) and in the end barely endurable (Polanski). The 15-minute intermissions were their own particular moment in time, perfectly adequate to prepare emotionally and physically for the end of one story and the start of another - unless the programmer had screwed up the timings and the projectionist was forced to show the films back to back, or even skip a reel.

In 1989 Derek Jarman wrote that, "The Scala is one of very few, and I'm afraid, a shrinking number of venues where it is possible for a young audience to see our film history. Any threat to the cinema is indirectly a threat to the industry as a whole, for here new audiences are educated and a whole generation that is active in our cinema has found its task."Maybe students who would have once spent their days and nights in the cinema are now too busy working to pay for their studies. Even so, it is hard to appreciate fully the efforts being put into the software of digitizing film for an occasional, sanitized big screen experience when you consider that our gorgeous old movie palaces were allowed to close. On Monday 7 June 1993 at a midnight wake the Scala showed its last film: King Kong, a tribute to the death of a loveable giant. There was no supporting feature that night.

As I write this, Time Out's London cinema listings show just a handful of polite double bills, but I laughed out loud at the Roxy Bar & Screen's offering of My Fair Lady (175 mins) + West Side Story (151 mins) - with a five-minute break scheduled between them. Now that's hardcore.