Primary navigation

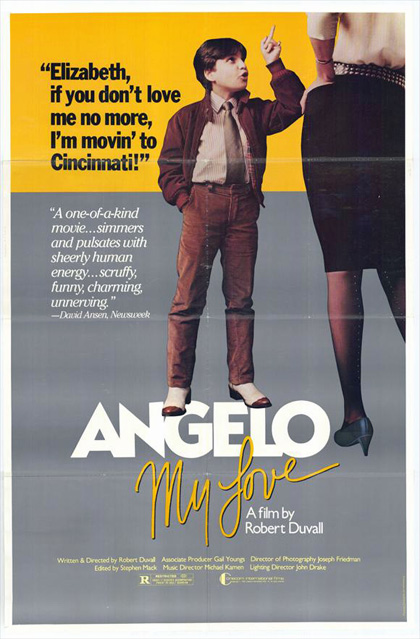

In the first of a new regular column about overlooked gems, David Jenkins makes the case for Robert Duvall’s Angelo My Love

A knee-high lothario with dark, feathered hair, who can’t be more than ten years old, struts down a dirty, early 1980s New York sidewalk with his teenage brother. Gold jewellery around his tiny wrists, he’s clad in a miniature tailored suit and a wide-collared shirt unbuttoned to his chest. He looks every bit the prepubescent Tony Manero, Travolta’s strutting disco king from Saturday Night Fever.

The pair turn into a discotheque where they engage in some wiseguy patter with the doorman, who waves them straight inside. The boy makes a beeline for the dance floor and soon a crowd of admiring (and much older) onlookers has formed, clapping as he flaunts his dance moves.

The street-savvy kid is Angelo Evans, the eponymous star of Angelo My Love (1982), the self-financed and long-since neglected second feature directed by Robert Duvall. Evans is of Greek gypsy descent, and Duvall’s film was an attempt to craft a truthful, ethnographic portrait of this seldom-documented New York enclave. Duvall spent time with various eminent New York gypsy families to get a feel for the daily rhythms of their lives; though the film is not strictly a documentary, the cast – including much of the actual Evans clan – are essentially playing themselves.

Duvall first encountered Angelo in 1977 on New York’s Upper West Side, where he was distributing leaflets advertising his mother’s fortune-telling business. The then eight-year-old was engaged in a heated quarrel with a grown woman, using syntax and gesticulation that belied his tender years. Here was a hepcat huckster trapped inside the body of a child. As with Bruno S. in Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), there’s a sense that Angelo’s real and screen personae are close – that his performance is both authentic and nakedly emotional. Duvall clearly recognised what he had in front of him, because for much of the film he simply allows his camera to observe, with affection, Angelo’s largely carefree passage through life.

Duvall had previous form behind the camera: his directorial debut We’re Not the Jet Set (1977) was a documentary, and the discipline of distanced observation clearly informed his approach to Angelo My Love. It’s remarkable to consider that Duvall took time out from a successful acting career to make a grubby, vérité comedy-drama like this – particularly at a time in his career when he had recently delivered a pair of mercurial leading performances in The Great Santini (1979) and True Confessions (1981).

In structuring the film, Duvall rejected exposition in favour of plummeting us directly into the mêlée of gypsy life. The story itself is slight, concerning ongoing tensions between Greek and Russian gypsies, with Angelo trying desperately to recover a stolen family heirloom from an oafish inebriate named Patalay. An anarchic kangaroo-court scene in which Patalay is accused of his crimes amid much hollering from the gallery is a bellwether of things to come, especially the moral grey areas within which some of the characters (including Angelo) furtively operate.

The film’s episodic narrative is entirely at the service of texture and characterisation; where some scenes might appear extraneous – such as Patalay’s violent, screwball quarrels with his constantly nagging wife – the salty idioms and heavy accents of the dialogue more than justify their inclusion. Brilliant, minuscule touches also abound, as in the scene when Angelo pokes his head out of a sunroof as their car hurtles down a motorway. It’s the kind of innocuous shot that screams cinematic construct and yet, in context, this minor, reckless action feels totally in keeping with Angelo’s impulsive character.

The films of John Cassavetes seem a key influence, evident in the way that Duvall uses edits sparingly and mines drama through letting conversations and monologues run to their natural length. There are hints of Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973) in there too, specifically the way in which Duvall manages to unpick and expand the social stratum of this closeted community.

But it’s two Italian films that linger in the mind when watching Angelo My Love. The first is De Sica’s neorealist lodestone Bicycle Thieves (1948), whose story, characters and thematic objectives are virtually indistinguishable (though Angelo is less pointedly political). The other is Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria (1957), specifically its depiction of a character driven (sometimes erroneously) by spiritual faith. For Angelo, religious devotion (plus a dash of gypsy mysticism) is his defining moral compass, even when it points him in the direction of violence. A scene in which he appears quietly enraptured by a candlelight procession during the Feast of St Anne harks back to Giulietta Masina’s blinkered nymphet in the Fellini film, idly consoled by her fervent piety.

The film’s New York-based distributors Cinecom saw Angelo’s street-smart charm as a marketing hook, and appearances by Duvall and his young star in the press and on television resulted in some surprisingly robust domestic box office on its release in the US in April 1983. The film went on to screen out of competition at Cannes in 1983, but despite receiving a generally positive critical response, its international roll-out was more muted: it opened on just two screens in London in July 1984, and has rarely been seen since.

Like Duvall’s 1997 directorial follow-up The Apostle, in which he stars as a travelling Pentecostal preacher with a penchant for settling scores with violence, this is a film about the poetry and drama of the irrational. It endures because it strikes a balance – critical without being unkind, empathetic without being overwrought, watchful without being voyeuristic. Is it a lost masterpiece? Probably not, but the endearing raggedness of its construction chimes perfectly with the essence of its subject-matter, making it not just a perceptive chronicle of a specific subset, but an example of a filmmaker successfully marrying form with content.

At time of writing, it’s actually easier to obtain a poster of Angelo My Love than one of the VHS copies knocking around eBay (though a near-complete version of the film has been posted on YouTube). Whether or not this column is intended as a clarion call for esoteric DVD distributors to pull their socks up, it would be swell if Angelo could live and be loved once more.

“Maybe because he’s such a good actor, Duvall has been able to listen to his characters, to really see them rather than his own notion of how they should move and behave. There are moments when the camera lingers… and scenes that do not quite dovetail into everything else, and we sense that Duvall left them in because they revealed something about his Gypsies that he had observed and wanted to share.”

— Roger Ebert, Chicago-Sun Times June 1983

“Circling Angelo to catch his worldly innocence from all angles, the camera seems… sometimes almost idolising of the golden days of youth.”

— Michael Cullingworth, Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1984

Tony Manero reviewed by Jonathan Romney (May 2009)

Open ear open eye: Tom Charity compares two versions of John Cassavetes’ radical 1959 improv film Shadows (March 2004)

Invincible reviewed by Richard Falcon (April 2002)

Nights of Cabiria reviewed by Geoffrey Macnab (October 1999)

Divining the real: Peter Matthews argues for the rehabilitation of André Bazin, high priest of realism (August 1999)