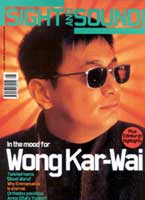

In The Mood For Edinburgh

In the Cannes press kit for In the Mood for Love - a collector's item, in that it's crammed with stills from scenes no longer in the film - Wong Kar-Wai describes the shoot as "the most difficult experience in my career". What was envisaged and planned as a low-budget quickie, to be filmed in Hong Kong with two lead actors and a small supporting cast in spring 1999, wound up taking 14 months to script, shoot and edit. Some of Wong's long-term collaborators left the crew during this agonisingly protracted process. Much of the original Hong Kong footage was supplanted by revised scenes filmed in Bangkok; a coda set in Angkor Wat in Cambodia was added at a very late stage and shot little more than a fortnight before the film's world premiere in Cannes. The first (seriously faulty) answer print came out of the lab in Bangkok on 16 May, just four days before that premiere. "We are physically and financially exhausted," says Wong in his Director's Note - a wry understatement.

But In the Mood for Love (Huayang Nianhua) is one of his best films, a gorgeously sensual valse triste that circles the themes of fidelity and sincerity in relationships before resolving itself into a requiem for a lost time and its values. The film opens in Hong Kong in 1962. Maggie Cheung plays shipping-office secretary Mrs Chan (née Su Lizhen, the name of her character in Days of Being Wild, 1990), a Shanghainese woman who rents a room for herself and her husband in the apartment of Mrs Suen. Moments after she has clinched the tenancy, writer and newspaper editor Chow Mo-Wan (Tony Leung) turns up to enquire about the room; Mrs Suen refers him to her neighbour Mr Koo, who also has a room to let. Mrs Chan and Mr Chow develop a nodding acquaintance as neighbouring tenants - until the day they lunch together and admit to each other that their respective spouses are having an affair. From then on, Chow finds excuses to spend as much time with her as discretion allows, inviting her to collaborate on his fiction and rehearsing with her the emotional showdowns they expect to have with their spouses. Ostensibly trying to understand how and why the adulterers began their affair, Chow seemingly intends to seduce and then jilt Mrs Chan - a displaced attack on her husband for seducing his wife? - but finds himself falling in love.

Wong never shows us the faces of the adulterers but focuses almost fetishistically on Mrs Chan's swanky cheongsams and Mr Chow's brilliantined self-doubt as they negotiate their quotidian routines. Her average day consists of typing, helping her urbane boss to keep his wife and mistress apart, going to the pictures and market-shopping for food; his of slaving to meet deadlines in a newspaper office and keeping pace with the whoring and gambling excesses of his colleague Ah Ping (played by the film's props master, Siu Ping-Lam). The film plays on patterns of repetition and variation, seeing them as droll but also faintly absurdist. By stressing that the central characters are surrounded by (off-screen) sexual licence, and by leaving their own desperate bid for ecstasy to the viewer's imagination, Wong somehow succeeds in defining an entire world on the brink of extinction. He ends the film in 1966, the year that anti-colonial rioting broke out in Hong Kong, clearly inspired by the Cultural Revolution in China. Mrs Chan is now a single parent in Hong Kong; we are left free to speculate who might be the father of her child. Mr Chow is a journalist based in Singapore; after an unrewarding visit to Hong Kong he finds himself in Phnom Penh covering General de Gaulle's state visit to Cambodia - and whispering a secret into a hole in a ruined wall at Angkor Wat.

Since winning two prizes in Cannes (Best Actor for Tony Leung and the Grand Prix for Technique) Wong has continued work on the film, mixing a Dolby stereo soundtrack and fine-tuning a few details. On the night of 19 June he was back in a sound studio in Kwun Tong to re-record one changed line of dialogue; we talked into the small hours once he'd finished.

Tony Rayns: You were like a zombie when I last saw you a few days before you left for France, and the film still wasn't finished. How did you get through Cannes?

Wong Kar-Wai: We were supposed to reach Cannes on 17 May but we didn't finish the mono mix of the soundtrack until the day before. That night we received the first answer print from the lab in Bangkok, for subtitling in French here in Hong Kong. But when we checked the copy we found that the sound wasn't right, the shots weren't right, everything was wrong. So we had to call everyone in Bangkok at 5am to remix parts of the sound and recut parts of the negative. And even when we got a corrected print we found a problem with the optical sound on one reel - so that reel had to be redone in Bangkok and hand-carried to France, to be subtitled in Paris on the morning of the first screening.

We finally got to Cannes around 7pm on the 19th. The screenings were scheduled for the following day - the press show in the morning and the official screening in the evening. We had a quick dinner with our friends, got a bit drunk, and then went to a late-night test screening with all the distributors who had pre-bought the film. Each distributor came with different expectations; they'd all seen different bits and pieces of the rushes, and they'd heard different things from me - depending on when we'd discussed it - about the story, the ending and so on. Everyone came out of the test screening shit-faced, nobody said anything much, and I went back to my room and told my wife I thought we'd have problems next day. But by the time we got to the press conference 12 hours later we'd heard from our PR people and others that the reaction at the press show had been very good. And the official screening went very well too.

How long was it since you'd had a full night's sleep?

I guess about four months. I haven't recovered yet. I try not to look at the film now, it's still too painful.

Do you know why it took so long for this film to coalesce into its final form?

The project had a very complicated evolution. It goes back to 1997, when we had the idea of making two films back-to-back, one before the handover of Hong Kong, the other after. The first of these was supposed to be Summer in Beijing, starring Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung, but we couldn't reach an agreement about filming in Beijing with the China Film Bureau and so we had to give up. But the actors were still on-side, and I didn't want to let the project die. My first idea was to go ahead with Summer in Beijing - with 'Beijing' now being a restaurant in Macau. That led to the thought of making a film about food and we came up with three strands of story, one about a chef, one about a writer in the 60s and one about a delicatessen-owner. At that time Maggie was supposed to be doing Memoirs of a Geisha for Steven Spielberg, so we thought we had only a short time to get it done. We planned the story about the delicatessen-owner and then moved on to the one about the writer - at which point I realised that the one about the writer was the only one I really wanted to make.

It evolved as it went along. At first we thought it should be set only in 1962, and then it expanded to end in 1972, spanning a decade in the lives of two people. But after 14 months of filming we realised it was impossible for us to make a film on that scale. So we forgot about the 70s and decided to end the story in 1966.

It took me a long time to decide what the end should be. Is it basically a love story about these two characters? Finally I think it's more than that. It's about the end of a period. 1966 marks a turning point in Hong Kong's history. The Cultural Revolution in the mainland had lots of knock-on effects, and forced Hong Kong people to think hard about their future. Many of them had come from China in the late 40s, they'd had nearly 20 years of relative tranquillity, they'd built themselves new lives - and suddenly they began to feel they'd have to move on again. So 1966 is the end of something and the beginning of something else.

Why did you go to Cambodia for the coda?

It was partly an accident. We needed something to make a visual contrast with the rest of the film. It's a bit like scoring chamber music; we needed some counter-balance, something about nature, something about history. We were shooting in Bangkok at the time and so we looked at all the city's temples or wats, but we couldn't find anything that was strong enough for our purposes. Our Thai production manager was the one who suggested Angkor Wat. I thought he was crazy, but he assured us it wasn't as difficult as we imagined. We could spare only five days because we were due back in Hong Kong for post-production and Cannes was looming. Thanks to our production manager's connections, we got permission to shoot from the Cambodian government within 48 hours. We shot over the Cambodian new year. We were supposed to film for only one day, but we ended up spending three days there. And when I found out that de Gaulle had visited Cambodia that year, I wanted that in the film too. De Gaulle is part of the colonial history that's about to fade away.

During the editing I saw a scene with Mrs Chan (Maggie Cheung) in Angkor Wat: Chow sees something of her face in a Japanese tour guide and later imagines a conversation with her. But it's not in the final cut.

The reason we originally planned a one-day shoot was that we needed only one scene - the scene now in the film. But Maggie didn't want to miss the chance to see Angkor; she even volunteered to come along as the stills photographer. And then, since she was there, we thought we might as well do something with her. We might yet find a use for that footage. I'm thinking of putting some of our unused rushes on our website.

You make it clear that many of the supporting characters are having illicit sexual relationships, but the central couple do everything possible to repress their feelings for each other. You've even cut the one scene in which they have sex; instead, you show them holding hands in a taxi, implying they'll spend the night together. Is there some link between their repression and the period?

I cut the sex scene at the last moment. I suddenly felt I didn't want to see them having sex. And when I told William Chang [Wong's production designer, editor and closest collaborator], he said he felt the same but hadn't wanted to tell me! You know, what kept me working on this film for such a long time was that I became addicted to it - specifically, to the mood it conjured up. I most of all wanted to capture that period, which was a much more subtle time than our own. From the very beginning I knew I didn't want to make a film about an affair. That would be too boring, too predictable, and it would have only two possible endings: either they go away together or they give each other up and go back to their own lives. What interested me was the way people behave and relate to each other in the circumstances shown in this story, the way they keep secrets and share secrets.

Why didn't you show his wife and her husband?

Mostly because the central characters were going to enact what they thought their spouses were doing and saying. In other words, we were going to see both relationships - the adulterous affair and the repressed friendship - in the one couple. It's a technique I learned from Julio Cortazar, who always has this kind of structure. It's like a circle, the head and tail of a snake meeting.

And that relates to the patterns of repetition and variation in the film?

I'm trying to show the process of change. Daily life is always routine - the same corridor, the same staircase, the same office, even the same background music - but we can see these two people change against this unchanging background. The repetitions help us to see the changes.

You've tackled the 60s once before, in 'Days of Being Wild', and you've suggested in your Director's Note that this film might answer the question "Whatever happened to 'Days of Being Wild, Part II'?" How do you see the relationship between the two films?

Days of Being Wild was for me a very personal reinvention of the 60s. Here, though, we consciously tried to recreate the actuality. I wanted to say something about daily life then, about domestic conditions, neighbours, everything. I even worked out a menu for the period of the shoot, with distinctive dishes for different seasons, and found a Shanghainese lady to cook them so that the cast would be eating them as we shot. I wanted the film to contain all those flavours that are so familiar to me. The audience probably won't notice a thing, but it meant a lot to me emotionally. When we started filming the 1962 scenes, William Chang asked me if we were finally making Days of Being Wild, Part II. I'll never make Part II as originally envisaged, because that story doesn't mean the same to me any more. But this is in some sense Part II as I might conceive it now.

On top of all your work on this film you've been trying to make progress with your sci-fi movie '2046'. Where does that stand?

Trying to work on both films in parallel was like falling in love with two people at the same time. 2046 comprises three stories, each inspired by a western opera, and we've more or less shot two of them. We went to Bangkok to shoot one and every time I went out looking for locations I found myself thinking we should have shot In the Mood for Love there. And so I moved production of In the Mood for Love to Bangkok, when problems with the actors' schedules forced us to suspend work on 2046, and we shot many additional scenes. And while we were shooting them I kept thinking, "Hey, this should be in 2046!" I became almost schizophrenic about the two films. Finally I told William I would stop thinking of In the Mood for Love and 2046 as separate films; I now think of them as one film. They're closely linked. You can find some things in this film that relate to 2046, and there'll be traces of In the Mood for Love in 2046 when it's finished, too. For example, the element of Chow's secret in In the Mood for Love is actually from 2046.

Production of 2046 will resume later this year. The third storyline, which is the longest, needs a big set and we plan to build it in Korea. The city council of Pusan is very supportive and we're now discussing with them how to shoot there. If everything goes smoothly, we'll resume filming in Korea in September.