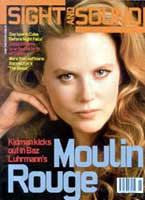

Paris Match: Godard And Cahiers

What was it about post-war Paris that produced Godard, Cahiers and the New Wave? Geoffrey Nowell-Smith looks back in languor at a time for fun and political ferment

For a young artist or intellectual, Paris just after World War II was a good place to be. It's true there were shortages, especially of heating fuel. But if your flat was cold, why not go out to a café where you might catch a glimpse of Jean-Paul Sartre or Juliette Gréco? Or, better still, go and watch a film. For this was a great period for the movies. French cinema itself wasn't particularly spectacular. Those leading directors of the 30s - Renoir, Clair, Duvivier, Ophuls - who had escaped to the US in 1940 weren't all in a great hurry to return. Those who had stayed, like Carné or Grémillon, or had emerged as new talents during the occupation, such as Clouzot or Clément, seemed uncertain what direction to take in the new circumstances. But there were other cinemas. There was in particular Italian neorealism, and British films were surprisingly popular - Ealing comedies, Olivier's Shakespeare, Powell and Pressburger. Most of all there was Hollywood. For five years since the fall of France in 1940, no US films had been imported except for a few smuggled in clandestinely from Spain or other neutral countries. The French public hadn't seen Gone with the Wind (1939), or His Girl Friday (1939), or Cover Girl (1944). Nor had it seen Citizen Kane (1941), about which Sartre wrote excitedly from New York in 1945. These and several hundred other films were awaiting the signature of an agreement between the French and US governments to allow the reimportation of movies into France. This was signed in May 1946 and the deluge began.

The film culture that developed in Paris in these conditions was unlike any other. Besides regular cinemas, there was a revival of the 'art et essai' circuit and there were countless cine-clubs, the groundwork for which had been laid in the resistance. There was Henri Langlois and the Cinémathèque française, which had mysteriously grown during the war years and now offered a complete course in film history from a somewhat unorthodox standpoint. And there was a culture of little magazines, kept going by the enthusiasm of writers more than by readers, who were far from numerous. There were enough readers, however, for the prestigious publisher Gallimard to relaunch La Revue du cinéma in 1946 and keep it going for three years.

La Revue du cinéma was edited by Jean-Georges Auriol, who had run a magazine with the same title and the same didactic purpose 15 years earlier. His assistant was a young man called Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, who recalled later that their office at Gallimard was opposite that of Albert Camus - to whom they rarely spoke, since Camus had no interest in films. Camus was an exception. Most of the leading figures in French intellectual life, from Cocteau to Sartre, were fascinated by the cinema. It was also the object of political contention. The influx of American films was seen by many on the left, the communists in particular, as a threat not only to French jobs but also to French culture, and as an insidious weapon in the Cold War. As the Cold War intensified, so did the split in French film culture. The left seized control of the fortnightly film magazine L'Ecran français, driving out André Bazin, a left-inclined Catholic who had tried to the last to maintain bridges between different tendencies. Besides writings by Bazin, L'Ecran français had also published the famous article 'Birth of a new avant-garde: the Caméra-Stylo' in which the critic and film-maker Alexandre Astruc foresaw the emergence of a cinema that would be a 'means of writing as flexible and as subtle as written language'. The loss of Bazin and Astruc was bad news for L'Ecran français and for French film culture in general, but it was also to have an unexpected result.

In 1948, the year of the publication of Astruc's article, Auriol had died in a car crash shortly after Gallimard had closed down La Revue du cinéma. Doniol-Valcroze set about trying to create a new forum to take its place and to provide a platform for Bazin and his tendency. Gallimard refused to yield up the title La Revue du cinéma, so Doniol-Valcroze and his friend Léonard Keigel founded a brand-new magazine to which they gave the name Cahiers du cinéma, the first issue of which came out in April 1951 - almost exactly 50 years ago - and which is still in existence.

In its first three years of life Cahiers du cinéma, under the editorship of Doniol-Valcroze, Bazin and Lo Duca and managed by Keigel, had no very distinct editorial position. It inherited from La Revue du cinéma an openness to what was new together with an uncertainty as to what this was. Welles was new, there seemed no doubt about that. Neorealism was new, but was it really different from other forms of realism, as claimed by Bazin and some other Catholic critics? Was the novelty of Welles related to the novelty of neorealism? What else was new in US cinema? The Revue had even suggested the left-wing playwright Clifford Odets as a film-maker to watch, but Cahiers began slowly to edge in a different direction. It agreed with its British counterpart Sequence in enthusing about Nicholas Ray, whose first feature They Live by Night was released in 1948. But it was also moving towards a new valuation of Hitchcock, whose early American films were coming out in somewhat random order in Paris in the late 40s and early 50s. And thanks to Henri Langlois and the Cinémathèque, Cahiers - in the person of Jacques Rivette - was soon to make its crucial rediscovery of Howard Hawks.

Cahiers was not the only magazine to provide a platform for these discoveries. The Ciné-Club du Quartier Latin not only showed an interesting range of films but for a while produced its own magazine, the Gazette du cinéma, a crudely printed rag whose editor was Maurice Scherer, later to become famous as a critic and film-maker under the name of Eric Rohmer. Like Bazin, Scherer was a Catholic and like Bazin he came to believe in an intrinsic realism of the cinema. But he had reached this view by a different route and held his position in a way that was intellectually uncompromising but allowed room for other tastes. He was the first of the French writers to take a philosophical line on Hitchcock, much to the subsequent amazement of the British who, as is well known, have never managed to take Hitchcock seriously at all.

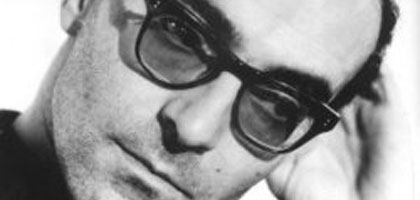

No fixed rules

Jean-Luc Godard was among those particularly enthused by Paris in those years. Though he had been born there, he'd spent most of his childhood and adolescence in the calm and safety of Switzerland. He returned to France at the end of the 40s to prepare for entry to university, but was quickly swept up into the cinephile culture of left-bank Paris. He was offered his first chance to write about films in 1950 in Scherer's Gazette du cinéma, at the age of 19. When the magazine folded he moved with Scherer to Cahiers. To tell the truth, in those early days he was not a good critic. Or, to be more precise, he was not a useful one. He was not the kind of writer whose reviews one could read to find out what a film was about. On the other hand, if you already knew the film, his comments were always illuminating. By the time he made his first feature Breathless (A bout de souffle) in 1959 he had become a very interesting writer indeed, and for the rest of his life he has remained as original a writer and thinker about cinema as he is a film-maker.

Godard's first encounter with writing about cinema was brief. After a handful of reviews and the occasional short essay, he left Paris again. He worked in Switzerland as a labourer building a dam and made a film about it. When he got back to Paris in 1956, Cahiers had changed. Bazin and Doniol-Valcroze were still the chief editors, but younger writers, led by François Truffaut, were setting the tone. The dominant tendency was now that of the 'politique des auteurs' and what Bazin disparagingly referred to as the 'Hitchcocko-Hawksian orthodoxy'. Renoir and Rossellini remained the most idolised European directors. Buñuel wasn't written about quite so often as in the early days. Mizoguchi had been discovered and was being promoted at the expense of Kurosawa. Among American directors, Lang, Ray and Preminger were established favourites, beside Hitchcock and Hawks. Fuller and Tashlin were new discoveries. Mankiewicz was slightly less admired than he had been at the beginning. These were tastes Godard was happy to go along with, but he never let himself be confined by them. He liked the early raw-edged Bergman of Summer Interlude or Summer with Monika in spite of his occasional artiness. He liked comedy a lot, and for a while even tried to claim auteur status for the forgotten and forgettable Norbert Carbonnaux. Most importantly, he was preparing himself to become a film-maker, and his film viewing and writing were stepping stones to this ambition. The films that mattered to him were films he could learn from: films with particular uses of the camera; films where one noticed the scene construction rather than the single shot; films whose characters seemed alive and real. He was distinctive among the Cahiers critics in his passion for films with a documentary basis. He admired Rouch and Resnais in particular. He rhapsodised about Rossellini's India ('India, c'est la création du monde') in the same way as he did about Bitter Victory ('Le cinéma, c'est Nicholas Ray').

Two obvious features mark Godard's criticism in the 50s. One is the incessant name dropping. He can hardly write a paragraph without referring to some extraneous poet, painter or playwright. This is on the one hand somewhat puerile. Rather than a proof of the depth of his reading, it tends to show up the superficial nature of his culture, which is that of a typical above-average French schoolboy studying for the fearsome Second Baccalaureate in order to get a place at the Sorbonne. On the other hand, it does have a purpose. References to poets, painters and playwrights function for Godard as ways of anchoring the cinema and giving it a place in the wider world of art. And references to Griffith, Murnau, Eisenstein and other founding fathers represent an attempt at a genealogy, tracing the broad trends back to some real or mythical origin. Given the random nature of his and his friends' viewing, dictated by erratic release patterns and the inspired but unpredictable programming of the Cinémathèque, this mapping of the history of the cinema is at times nothing short of heroic.

The second outstanding feature is a love of pun and paradox. This doesn't always come across well in English, though the translation by Tom Milne of Godard's critical writings in Godard on Godard is exceptionally good. A lot of the puns are merely jokey and can be exasperating in the same way as the name dropping. But their function is to create a kind of semiotic field in which disparate ideas are yoked together and unlikely similarities prospected, rather as James Joyce does in Ulysses or Finnegans Wake. The spirit is one of 'why not?' Since we don't know why the world is the way it is, why not imagine different ways in which the bits of it might connect? Neither art nor life appears to have any fixed rules, but patterns can be given to them by the imagination, out of which truth may emerge.

Digressions take over

During the 50s Godard made a number of fictional short films with his Cahiers friends. As far as he was concerned, these were strictly an apprenticeship for the real thing, which was making features. Short films, he remarked in Cahiers in 1958, weren't a genre; they were just films which were short. When he did make a feature - Breathless, in 1959 - it was a far greater success than he had expected. To a large extent this was a function of its time. The French cinema, as Truffaut and Godard and their friends had repeatedly asserted, was stale. There was a new public which wanted new films. The novelty it wanted wasn't necessarily a new aesthetic - mainly it just wanted new characters. This was what was offered by the New Wave. The New Wave had started a couple of years earlier, with Roger Vadim's And God... Created Woman (Et Dieu... créa la femme) in 1956 and Louis Malle's Lift to the Scaffold (Ascenseur pour l'échafaud) two years later. The Cahiers film-makers - Chabrol, Truffaut, Godard - were riding a wave which not only existed but also (though they weren't to know it) was about to peak. With its casual characters and casual style, Breathless epitomised the novelty the Parisian public in particular was looking for. Over 250,000 people saw it in Paris alone. Godard's career was made.

Later Godard was to remark that Breathless hadn't turned out as he'd expected. He'd wanted to make a realistic film (rather in the manner of what Chabrol and Truffaut were doing), but it came out different. The degree to which it was different escaped not only Godard but the public too, because when Godard started making films which really were different they didn't do nearly as well at the box office. His next film Le Petit Soldat (Little Soldier) was banned by the French censor because of its subject matter. 1961's Une Femme est une femme (A Woman Is a Woman), which Godard himself described as his first real film, was a box-office flop. His next, Vivre sa vie (My Life to Live, 1962), did better, but Les Carabiniers (Soldiers, 1963) was a disaster. The critics had learned to hate Godard while the general public had simply got bored. Le Mépris (Contempt), made at the same time and on a substantially bigger budget, did well enough, but the massive payment to Brigitte Bardot meant it wasn't profitable at the time. (Le Mépris was also Godard's only film to be changed - and in my opinion improved - at the behest of a producer.)

During this fertile period in the early and mid 60s Godard's aesthetic strategies became more and more daring. Each film was a new departure, posing a particular problem for which the director had to find a solution. There is no simple progression from the world of Breathless in 1959 to that of Weekend in 1967, but certain stylistic procedures become more accentuated. Most noticeable - and most often remarked on - is a move away from self-contained and unitary fiction. Alphaville and Pierrot le fou in 1965 are the last Godard films for a long while which basically tell a story. While the films up to this point are story films where the story is occasionally interrupted or undercut by non-narrative devices, by the time of Two or Three Things I Know about Her (2 ou 3 choses que je sais d'elle) in 1966 and La Chinoise the year later the storyline is so thin as to be virtually non-existent. Digressions have taken over the narrative.

Where Godard is most original is in his use of sound. If you watch an early Godard film on video with the sound off it looks quite normal. Turn on the sound and its originality becomes apparent. Godard realised very early on that sound is an element of montage and can be used either in an integrative or a disjunctive manner. This meant a break with the aesthetic inherited from Bazin and Rohmer and had implications for Godard's own feelings about the documentary basis of cinema. He had actually made this break critically back in 1956 with an article in Cahiers entitled 'Montage, my fine care', run opposite Bazin's own 'Montage: forbidden', but the real exploration of what this meant took place in his films from Une Femme est une femme onwards. It is in Une Femme est une femme that he starts breaking up music into short bursts, prefiguring the extraordinary use of a repeated haunting phrase from a Beethoven string quartet in Two or Three Things. And in Bande à part (The Outsiders, 1964) he represents the idea of a minute's silence not by having the characters fall silent but simply by mixing in no sound for the duration. These and other devices combine to give the sense of a film as a kind of assemblage - different bits of the material world put together in a particular way. It remains important that some of these bits are documents, culled from pre-existing reality, as in Godard's much admired Rossellini. But Godard moves on from Rossellini by treating this reality as there to be questioned. To Rossellini's rhetorical 'Things are there: why manipulate them?', Godard replies: 'Things are there: but let's see how they work.'

Reality, for Godard, is a mystery which is first encountered by experience and which activity sets out to solve. The main mystery for the early Godard is the human person, particularly when embodied in a woman. There is a repeated trope in his films where a woman asks a man if he loves a certain part of her body, and when he says 'yes' she names another part and then another, until finally she says to him, 'So, you love me totally.' (The most spectacular enactment of this is in Le Mépris, where the questioner is Brigitte Bardot lying naked on a bed.) In Vivre sa vie Paul tells the story of one of his pupils who wrote an essay on the chicken: 'The chicken has an outside and an inside and inside that is the soul.' Also in Vivre sa vie Godard quotes a phrase from the song in Ophuls' Lola Montès, apropos of Nana's decision to become a prostitute: 'Elle donne son corps, mais elle garde son âme.' ('She yields her body, but keeps her soul.')

Questions of the body, the soul, consciousness and what it is to be human crop up regularly in Godard's films up to 1965 and recur later in the 80s and 90s. They do not have to be posed in relation to women. In Alphaville Lemmy Caution arrives on a distant planet and is interrogated by Alpha 60, a computer who eventually becomes victim to Cartesian doubt and auto-destructs. Alpha 60 asks Lemmy about his experience travelling to the planet and Lemmy replies, in the famous words of the philosopher Blaise Pascal: 'The eternal silence of these infinite spaces terrifies me.' Alpha 60 then asks Lemmy about his beliefs and Lemmy says: 'I believe in the immediate data of consciousness.' The Immediate Data of Consciousness is in fact the title of a book by French philosopher Henri Bergson, known in translation as Time and Free Will. And Bergsonian vitalism, which Godard would have learned in school, is the dominant philosophy of all his early films and arguably also of his later work.

Foam in the espresso

Godard once expressed the wish to have been 20 years old at the time of the Spanish Civil War. Throughout the 50s and early 60s he was for the most part apolitical - he kept right-wing company and was in a vague way attracted to the idea of political radicalism, which might equally be of the right (the central character in Le Petit Soldat) as of the left (the Mayakovksy-quoting girl in Les Carabiniers). His equivalent of 30s Spain was Vietnam. From Pierrot le fou in 1965 onwards, his late-60s films are scattered with references to the US war in Vietnam, the most savage being those of the two radio-hams in Two or Three Things who purport to be picking up messages from the Yanks about ever more lunatic escalations of the war. Godard did not himself go to Vietnam, even as an observer. His contribution to the compilation film Loin du Viêtnam consists entirely of a soliloquy about his impotence in the face of the conflict. But impotent or not, he was radicalised by the war, and it led inexorably to a change in film-making style and philosophy.

Godard's early films are fun. They are humorous, they are beautiful, they are provocative. They have their detractors, and their public was never huge. But they enthused a whole generation of young people. Most of Godard's admirers followed him on his long march leftward from 1967 onwards. Some of them (or perhaps I should say, some of us) were there already. But as he began to consolidate around a political position, something got lost. With films like Wind from the East (Vent de l'est, 1969) Godard had begun to assault his audience in the name of new-found certainties. Bergson gave way to Marx; curiosity about paradox gave way to a formal exposition of contradictions. One exciting thing happened - the opening up, from Two or Three Things onwards, of a problematic of language. Godard's anxiety, in his Marxist period, ceases to centre on the body/soul dichotomy but on the relationship of words to images and images to things. This is brilliantly exploited in La Chinoise and in a more rarefied way in Le Gai Savoir (The Joy of Learning, 1968). But one very bad thing happened. When he abandoned commercial film-making, he lost the advantages conferred by commercial distribution. His films began to circulate in diminishing circles, mainly on 16mm. They also became the subject of ponderous disquisitions that seem designed to deprive them of their magic. Seen in 35mm, Two or Three Things I Know about Her not only dazzles philosophically, it is also visually entrancing: the swirl of brown foam in the cup of espresso encapsulates chaos better than any film image I know. Let's hope the retrospective at London's NFT will exorcise the demons raised by classroom screenings, which have done more to put people off Godard than hostile critics could ever do.