Comment

Antonioni: the afterlife

10 March 2011

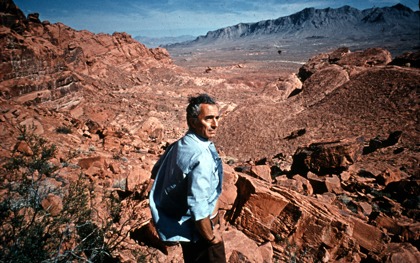

Michelangelo Antonioni on location for Blowup. Photo by Peter Theobald for Sight & Sound (1966)

Chris Darke pursues the spirit of the late Italian master through recent films, plays and books

After the deaths of Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman on the same day in July 2007, I turned on BBC2’s Newsnight to see what sort of coverage the demise of two giants of cinema merited. By the end of the item, I’d learned a couple of useful lessons.

First, it’s much less fun kicking in a flat-screen TV than one of the old cathode-ray tubes.

And second, if you fancy a slot as a cultural pundit, be willing to enthusiastically play the philistine. Narrowly outdoing the wretched Toby Young’s drawling consignment of both oeuvres to the dustbin of history, a youngish female commentator brightly announced that she’d rather “watch Bruce Willis in a vest” than endure any of the films by the recently deceased auteurs.

It was a shameful spectacle, but I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised. If one considers the subjects implied in the discussion – foreigners, their cinema, and the idea of ‘art’ – they made easy targets for the gleefully narrow-minded sensibilities on display. I imagine the shades of the Italian and Swede looking down from the great screening-room in the sky and sagely observing, “Well, that’s the British for you.”

The death of a major filmmaker can also spur more thoughtful reassessments. In Antonioni’s case, while the books keep coming (there’s at least two more imminent, which I’ll deal with shortly), the artistic responses in other mediums also contribute to the afterlife of his films, and it’s interesting to observe the contexts in which references to him continue to occur.

Michelangelo Antonioni on location for Zabriskie Point

I was intrigued to read a Newsweek critic nail Sofia Coppola’s Somewhere (2011), for instance, noting that “the one thing Coppola doesn’t steal from Antonioni is his class awareness; there’s never so much as a glimpse of the lives of, say, the maids in her ‘I’m rich but I’m depressed in a hotel’ movies.”

One could also cite Anton Corbijn’s The American (2011) as another case of a recent American film that attempts to ‘do Antonioni’ in terms of its pacing and use of silences, but succeeds only in a pale approximation of an idea of his style, and fails to generate any of the psychic afterimages his work invariably leaves lingering in the mind.

The question of whether style trumps substance was repeatedly levelled at the director’s own films; Antonioni was nothing if not a self-conscious stylist. Think of some of the endings to his films, where imagery slips free of narrative, characters disappear, and the pursuit of a kind of abstract beauty takes over. Now that a significant sector of the art world exists solely to quote and recombine elements from pre-existing films (recent examples being Christian Marclay’s cinema-sampling magnum opus The Clock (2010) and The Otolith Group’s ‘recontextualisation’ of Chris Marker’s 1989 TV series The Owl’s Legacy), I await the inevitable gallery show that would consist solely of the finales from L’eclisse (1962), Blowup (1966), Zabriskie Point (1970) and The Passenger (1975), each sequence eminently suited to being shown as an experimental movie in its own right.

Toneelgroep Amsterdam’s theatre production the Antonioni Project

Given its formal beauty and timeless mystery, Antonioni’s work would not be out of place in an art gallery. But putting it on stage: how might that work? This was the challenge that the Belgian theatre director Ivo van Hove set his company Toneelgroep Amsterdam in their Antonioni Project, which was staged at the Barbican in February. It was an ambitious, flawed but worthwhile experiment in adapting the director’s 1960s ‘trilogy’ of L’avventura (1960), La notte (1961) and L’eclisse to the stage.

Or rather, not the films, but the screenplays. In interviews, Van Hove was keen to stress that he hadn’t actually seen L’avventura, but I’m not sure I believe this.

I spent the first half of the two-hours-plus production checking off scenes I recognised – the minute’s silence in the Rome stock exchange from L’eclisse; the extended party sequence from La notte; the search for the missing girl on the deserted island in L’avventura: all were present and correct.

After a while, I gave up, as scenes and characters from the films mingled on stage amidst the complex multi-media choreography of a live jazz band, cameramen filming the action, and real-time projections on huge screens. Paradoxically, van Hove managed to transform Antonioni’s stark, abstract mise en scène into a teeming, baroque circus reminiscent of Fellini. Whether that counts as a success, I’m not sure. Nor was I convinced that the production achieved its aim of reasserting the present-day relevance of the films’ anatomisation of the frozen emotional lives of the bourgeoisie.

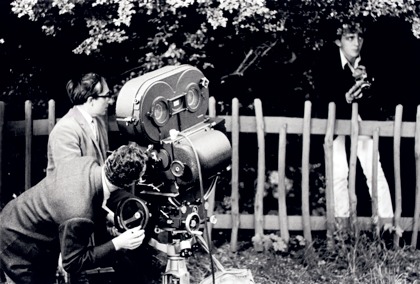

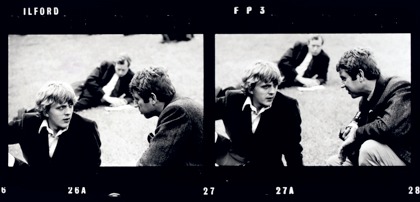

Shooting The Passenger

I’ll come back to Antonioni’s representation of middle-class characters and milieux, but it’s also worth mentioning the minor industry of critical evaluation that his films continue to elicit. In an essay for Cinema Scope, occasioned by the 2005 re-release of The Passenger, Robert Koehler characterised the film’s peculiar richness as follows: “See the film twice, and you see two films. See it a third, and you see a third. And so it goes.”

I feel the same way, and not just about The Passenger. Antonioni’s cinema is defined by its curiously ungraspable, indeterminate quality, which can be enriched by close study but is never exhausted by it. Canadian film scholar Murray Pomerance’s forthcoming Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema promises to examine the under-explored role of colour in his work.

After all, this was a filmmaker not averse to spray-painting trees and grass to get the ‘right’ hue of green, such as in Maryon Park, the South London location transformed into the site of a hypothetical murder and metaphysical quest in Blowup.

The German art-book publishers Steidl are issuing an excellent monograph by British art historians Philippe Garner and David Alan Mellor on Antonioni’s iconic Mod murder-mystery.

On location for Blowup. Photos by Peter Theobald for Sight & Sound (1966), courtesy Steidl publishing

Mellor conducts a forensic examination of the film as a crime-scene, replete with artistic references, and Garner unpacks every aspect of its pop-cultural textures. (We also learn that in the summer of 1966 Sight & Sound despatched photographer Peter Theobald to take on-set shots [see above and top] but was ejected by an un-amused Antonioni after a day.) One of the most acute texts on Antonioni is Roland Barthes’ short essay ‘Dear Antonioni’ (1980), in which he claims the filmmaker as “one of the artists of our time” and pertinently cautions that “the artist is under threat […] of the ever-present collective sentiment that a society can very well get by without art.” And we’re back to the sorry affirmation of this sentiment as it was presented on Newsnight.

But perhaps Antonioni provides us with another way of thinking about that calumny. Consider his film’s recurring depictions of bourgeois bad faith, whether in the pathetic character of the architect Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) in L’avventura, or the intellectual Giovanni (Marcello Mastroianni) prepared to sell out to an industrialist’s PR firm in La notte. On that night in 2007, as the hacks merrily rubbished the work of a pair of great film artists live on television, they appeared blithely unaware that they, too, were reprising the very same self-betrayal, playing their own parts in an Antonioni film.

‘Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema’ (University of California) is published on 21 March. ‘Antonioni’s Blow-Up’ (Steidl) is published in April. Antonioni’s early films ‘La signora senza camelie’ (1953) and ‘Le amiche’ (1955) are released by Masters of Cinema on Blu-ray and DVD on 21 March.

See also

The American reviewed by Michael Atkinson (December 2010)

Mobsters and maestros: Nick Hasted on a new generation of Italian filmmakers finally finding its voice (May 2010)

Radical chic: Chris Darke on Cannes’ hidden tradition of political radicalism (June 2007)

Geometry of feelings: Guido Bonsaver on Antonioni’s high modernism (July 2005)