Primary navigation

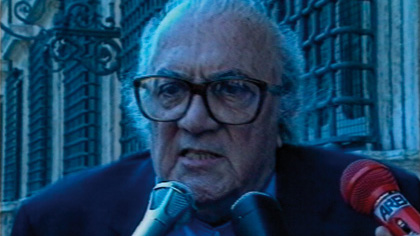

Il Divo

Cinematic nostalgia, endemic corruption and the deadening hand of Silvio Berlusconi have prevented Italy’s real story from being told on film for 30 years, says Nick Hasted. But now a new generation of film-makers is finding its voice

When Paolo Sorrentino’s Il Divo and Matteo Garrone’s Gomorrah caused a double sensation at Cannes in 2008, Sorrentino dryly noted, “Two films is rather few to launch a renaissance.” But in the last year Gianni Di Gregorio’s Mid-August Lunch (Pranzo di ferragosto), Marco Bellocchio’s Vincere and, most of all, Luca Guadagnino’s current festival barnstormer I Am Love have taken the count to at least five. Beneath these international successes, too, there has been a noticeable stiffening in the quality of Italian films.

If nothing else, these films help to remove the cultural cringe young Italian directors feel towards their own cinema’s past. The attitude of Saverio Costanzo, director of In Memory of Me (In memoria di me), was typical of his generation when I canvassed them in 2007. He felt oppressed by the old maestros. “They destroyed our cinema,” Costanzo mourned. “They consumed Italy by portraying it in such an absolute, timeless way. And I sometimes have the feeling that nobody cares what Italy is now. As young directors, we are working to escape this enormous legacy of ‘Why should I see Saverio Costanzo’s movie if I have an Antonioni?’”

Domenico Procacci, Italy’s most important producer even before he made Gomorrah, feels the weight of the past lifting now. “What’s happened in the last year, because of Gomorrah and Il Divo and a few other films, is that the perception of Italian cinema has changed a bit abroad. Often people say, ‘I loved your film. But La dolce vita is better.’ I quite agree! It’s difficult to compete with Fellini. But I think Italian film is becoming better known for what we are doing now.” I Am Love’s dazzling title sequence – cut, designed and scored to brashly recall some great Italian art film from 1960 – defines this new confidence. “We were trying to connect the chromosomic code of great movies that we love, from Visconti to Antonioni, with a vision of Milano today,” Guadagnino says. “You can’t start in a humble, hypocritical way, saying, ‘Those were masters and we are not.’ We have to say, ‘Let’s aim for the stars and see where we go.’”

What Do You Know About Me

But if Italian cinema now stands at a pivotal, hopeful point, it is still only taking the first steps in reversing a seemingly terminal 30-year decline. This is anatomised in another new film, Valerio Jalongo’s polemical documentary What Do You Know About Me (Di me cosa ne sai). It describes an industry a long way from the one that literally rose from the ruins with Rome, Open City (Roma, città aperta, 1945), propelled by the need to tell a national story suppressed by fascism and war. By the early 1970s that great tradition was at its popular zenith, with a generation of maestros enjoying international box-office success. But Italian cinema since then has reflected only Italy’s cultural devastation: an inward-looking attitude, hooked on bad television, and dependent on one man – if Fellini was the maestro of Italian cinema’s golden years, Silvio Berlusconi orchestrated its implosion. With rare exceptions, Italy’s national story from the 1980s until 2008 was defined by the great films it could no longer make.

Jalongo’s film lists most of the political choices in the 1970s that triggered the decline, most tellingly Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti’s replacement of the state subsidies that had previously encouraged international co-productions with ones for purely domestic work, and the 1976 legalisation of commercial television, which showed thousands of films over hundreds of (initially) unregulated channels and paid too little for them to fund new productions.

But Jalongo also suggests more shadowy manipulations behind the collapse, rising out of what Sorrentino calls “the occult nature of power in Italy” – he equates American cultural intervention with Italian state-sponsored violence. “In the last 30 years,” Jalongo says, “there have been a series of terrible massacres and bombs placed to kill civilians. In these cases we have never managed to reach the truth. I think the Americans were really worried, because the Christian Democrats were losing ground to the Communist Party. Something was done, using bombs and cultural intervention – there have been a lot of Italian secret-service convictions for these bombs.”

What Do You Know About Me sees 1975 as the moment when malevolent attention turned towards a thriving Italian industry that was challenging a Hollywood in commercial free fall since the 1960s. That year, Dino de Laurentiis led the sudden exodus of Italy’s most powerful producers from the country and Pasolini was murdered in murky circumstances, days after writing that he knew who was behind the carnage. “Then commercial television came,” says Jalongo, “and changed the political and emotional temperature in Italy in a matter of five years. Normally I’m not the kind of person who is always seeing a CIA plot, but I think there was planning, with complicity from Italian politicians.”

The Caiman

The previous healthy plurality of independent, entrepreneurial producers and distributors – able to fund an unprofitable first film by a Pasolini as part of broad portfolios – was squashed by commercial television’s voracious demands. By the 1980s, the state broadcaster RAI, which had begun its involvement in cinema by helping to fund Bertolucci’s The Spider’s Strategem (La Strategia del Ragno, 1970), was reduced to competing with commercial rivals. By 1985, Hollywood dominated the box office at cinemas that had halved in number since 1980; the state corruptly subsidised cheap Italian films there was nowhere to screen; the work of ageing auteurs clogged a sclerotic system. “The 1980s was worse than ashes,” says Silvio Soldini, director of the 2000 Italian hit Bread and Tulips (Pane e tulipani), who entered the industry during the decade.

“Of course some very good films by the Taviani brothers and Nanni Moretti got through,” says Jalongo. “But the mechanism of giving out money was entirely politically controlled. Your real counterpart was not the public any more, but the politicians who had to grant you the money and the producers who knew so-and-so. Of course, a closed system like that does not push people to try new things. It becomes an insider play.”

By 1994, the industry’s old plurality had finally disappeared. The state’s RAI and Berlusconi’s Mediaset/Medusa television empire financed almost every Italian film, with the purpose of filling their primetime schedules. Berlusconi’s election that year meant Italian cinema was subject to his exclusive approval.

“It’s not as corrupt now as it was 15 years ago,” Jalongo says, explaining how Italian cinema is at last rallying from these body blows. “After the worst case of corrupt politicians who were giving out money to unknown people, there was a fever for change. And in the last five or six years we have had people in key places who are honest and capable. Since 2007 we’ve had a very bright woman, Caterina D’Amico – the daughter of Suso Cecchi D’Amico [co-writer of Bicycle Thieves – in charge of RAI Cinema, and she is much more open. But at some point someone is going to say, ‘These films you financed don’t play well to our primetime audience.’ We also have a handful of very good producers now, like Domenico Procacci. But each of them is in a fragile position: they always have to bring projects to RAI or Mediaset. And each time those companies can say, ‘No, this project is not good for us. Sorry.’ If Berlusconi wanted to put Procacci out of business, he could do it with a phone call. That’s the system we have now.”

The Man Who Will Come

Insidious attempts at censorship continue. Giorgio Diritti, director of last year’s The Man Who Will Come (L’uomo che verrà), a carefully crafted rural film climaxing in a fact-based Nazi massacre of civilians, was startled by RAI’s reaction: “They asked, ‘Are you going to show the actual massacre?’ There was a great deal of unease.” Soldini, meanwhile, saw his film Days and Clouds (Giorni e nuvole, 2007) – about the aftershock of unemployment on a middle-class couple – rejected by RAI and Medusa. “When you speak about social problems, the television channels look at you very strangely,” he says. “They think people won’t go.”

Berlusconi has affected Italian cinema more indirectly. What Do You Know About Me shows how even television news bulletins are tailored to suit Auditel audience-approval ratings. Erik Gandini’s complementary documentary Videocracy shows the sexed-up game shows and talk shows propagandising Berlusconi the boss. “With his television stations, he’s succeeded in changing the people themselves,” Soldini believes. “He’s taken everything down to the lowest common denominator. We’ve all become children.” Jalongo sadly agrees: “Italians are sedated by television, and by this political situation. When we had a strong, controversial, aggressive cinema, there was a lot of debate and depth in our cultural scene. Not any more.”

I Am Love

Italian cinema’s aesthetic ambitions were also crushed by being cheaply funded to fill bad television channels. Guadagnino, whose I Am Love quivers with stylised sensuality, passionately loathes the results. “I feel that after 20 years we have to regard Berlusconi as someone who has changed Italy completely,” he declares. “He’s won, totally and utterly.” As an example Guadagnino cites the recent Kiss Me Again (Baciami ancora), Gabriele Muccino’s sequel to his 2001 hit One Last Kiss (L’ultimo bacio): “When you see Kiss Me Again, the new film from Muccino – a strong director with a very successful history [he has also directed the Will Smith films The Pursuit of Happyness and Seven Pounds – produced by Domenico Procacci, the best, most important Italian producer today, you see that this middlebrow, superficial attitude to telling stories and depicting reality has won. There is a self-censorship in which you say to yourself: ‘I have to cast these people and tell these stories this way.’ In Italy, comedies have to be able to fit into the little screen of the television and be very easy-going and imitative – the effect of Friends and Desperate Housewives. Muccino has generated a very long wave of neurotic semi-comedies about bourgeois people in their mid-thirties.

“And then you have Paolo Sorrentino,” he continues, “using all the tools of commercials and video clips to paint glossy, typical Elio Petri Investigation of a Citizen above Suspicion grotesque stories like Il Divo. So what is the state of Italian cinema from the 1990s to the 2000s?” he concludes with a flourish. “I would say it’s televisual.”

“Television has conditioned cinematic forms in a crushing way – and not just in Italy,” Bellocchio agrees. “But whoever has talent can use that ‘language’, which is so foreign to the cinema, and personalise it. The margins of autonomy in the area of beauty, refinement and care are slight. But it’s there that we must concentrate our attentions.”

My Brother is an Only Child

Guadagnino and Sorrentino are their generation’s only genuinely, radically different high stylists. But part of Italian cinema’s thematic revival in the last few years has come from trying to confront the reign of bombs and terror that Jalongo thinks is inseparable from its 1970s collapse. With direct comment on the present almost impossible, ghosts of a violent past crowd these films. Daniele Luchetti’s My Brother is an Only Child (Mio fratello è figlio unico, 2007) sees one 1970s brother side with communist terrorists while the other becomes a fascist. Michele Placido followed his polished Mob hit Romanzo criminale (2005) with The Big Dream (Il grande sogno, 2009), a soft-focus saga drawn from his own experience as a policeman undercover amidst 1968’s Rome student protests; scenes in which policemen in fascist-era uniforms break heads echo the right-wing present. Bellocchio’s Good Morning, Night (Buongiorno, notte, 2003) ends its meditation on Christian Democrat leader Aldo Moro’s 1978 kidnapping and murder by the Red Brigade with Moro magically walking free, as if the long national nightmare of his death might be woken from. Il Divo lances the same trauma by making Andreotti, the prime minister blamed for letting Moro be killed and backing state terror, confess. “The objective was to create a sort of catharsis for the audience,” Sorrentino says. “It felt necessary to scream out some responsibility.”

The current discomfort of some Italians with any sort of critical cinema was displayed last year after a London Film Festival screening of Gabriele Salvatores’ As God Commands (Come Dio comanda), a gruelling, darkly beautiful thriller centring on Filippo Timi’s unemployable neo-fascist father in Italy’s depressed north-east. “Is it correct to present Italy in this way to the world?” a woman asked indignantly. “It’s not ‘correct’,” Salvatores told her. “It’s not right that we have a situation like this.”

Above investigation

Aside from Nanni Moretti’s brave The Caiman (Il caimano, 2006), which satirised Berlusconi (with mostly French backing), the central figure of Italy’s last 15 years has only been dealt with obliquely. Maybe, like Hollywood’s decade-late Vietnam cycle, it’s simply too soon. “It’s very hard for us to portray what’s happening in Italy,” says Costanzo. “Or maybe we are not talented enough. But nobody’s succeeded in making a movie about Berlusconi. That’s because Italian reality is stronger than our imagination. Berlusconi is already a movie, already something that you cannot imagine. Maybe in 20 years [films will depict him], when we get out of it.” Il Divo drops his name twice alongside Andreotti. “At the beginning, there’s a glossary,” says Sorrentino. “Berlusconi is mentioned as being in the P2 Masonic Lodge.” I Am Love also leaves only the subtlest clue to real-life comparisons with its wealthy northern Italian family’s cold heart. “You see the father reading Il Giornale, the newspaper published by Paolo Berlusconi, the brother of Silvio,” Guadagnino smiles. “I would like to make a movie about Berlusconi coping with his own interior reality, in the solitude of the moment in which he’s shitting, or waking up.”

Vincere

Bellocchio’s Vincere may be the bluntest critique. Stylistically concerned with Mussolini’s mastery of the media, lingering on minutes of archive footage of his strutting speeches, it lets you really look at the fascist leader Berlusconi helped to rehabilitate. Bellocchio has denied comparisons, however. “I didn’t want to draw parallels,” he explains, “because although they were both political figures who had a strong sense of their public image – Mussolini through the use of film and Berlusconi through television – Berlusconi never tried to overthrow democracy in Italy. He tried to influence it, yes, but Mussolini threw people in jail. His was a brutal dictatorship that did not allow freedom of speech. The climate of intolerance and censorship was worse when I started in 1965, too. If I didn’t draw parallels, it wasn’t a tactical means to avoid harming the film.”

“Well, he [Bellocchio] didn’t say that at the beginning,” Jalongo counters. “He was saying ‘Yes, of course they have a lot in common.’ But you shouldn’t be too harsh on this kind of watchful behaviour: Berlusconi is a dangerous man. Fellini called him ‘the gangster’ in private. His methods and the people he has around him right now are really scary. He’s not just referring to fascists by the way he dresses or the way he acts – the violence of the current clash in the political arena is really frightening. I wonder what will happen.”

Berlusconi’s influence on Italy’s cinema is baleful and profound. But he’s not a full alibi for its failings. “We screenwriters and directors are also to blame,” Sorrentino says bluntly in What Do You Know About Me. “Too often we make films that lack courage, about obsolete subjects. Plus, everyone says quality has suffered because audiences want inferior products. But what if audiences wanted paedophilia and incest? Do we give it to them?”

At the the London Film Festival three years ago, Film Italia’s annual cinematic cross-section included films whose makers complained to me about Berlusconi holding them back, but whose shoddy amateurishness didn’t deserve release. In 2009 the same event showcased As God Commands, which framed its scenes of clammy horror like a grimly beautiful fairytale, catching the social fractures in a chilly, jobless northern town while keeping its genre grip. Even more encouraging was debutant Guiseppe Capotondi’s vertiginous noir The Double Hour (La doppia ora), which conjured dread from sounds in the dark. Previously a pop-video director, Capotondi should join the truly new generation of Italian film-makers whose arrival was first announced by Sorrentino’s The Consequences of Love (Le conseguenze dell’amore, 2004), with its American-schooled flash and vigour and mordant Italian grotesques.

Gomorrah

Anyone still mourning the era of the old maestros in this context, or expecting a flood of fresh talent through the cracks opened by Gomorrah, doesn’t understand the Italian industry’s hierarchical, insular nature, as Guadagnino explains. “I think we will have more strong personalities coming along, like Sorrentino or Garrone. I don’t think the international success of these single films will become a wave – the industry doesn’t believe in that at all. It has almost no interest in the outside world. The problem is that Italy is about the importance of individuals. So they would say, ‘He is Garrone.’ They wouldn’t say, ‘This 21-year-old could make a Gomorrah,’ because that person isn’t Garrone. When I was preparing my first film The Protagonists at the age of 26, my friend the late Laura Betti, the singer and friend of Pasolini, said to me, ‘Remember, you’re a baby to them. And you will be regarded as a baby for a long time.’ Just now, I’m turning into a ‘young’ director. And I’m 38, I have a white beard.”

“It’s true that Gomorrah was very successful in Italy and outside,” producer Procacci concedes. “The problem is that in a great moment like the one we lived in 2008, you should build. You should have a strategy. You should invest. And in Italy, exactly the opposite happens. No one invests, and they’ve reduced the funds. In a culture we love, we don’t have a cultural policy. It’s absolutely tough, tougher than a few years ago.”

“2008 changed perceptions; there’s been a little more interest at home for Italian films,” Jalongo agrees. “But the producer who made Il Divo did not earn one penny from that movie, even though it’s been successful worldwide, because of the contract he has with Medusa, and not being able to sell it to television because of its subject. In a normal country, he would be a very successful producer now, with a slate of new productions. If the system is not good enough, it’s killing you.”

It may be no coincidence that Berlusconi was out of power in 2007, when a cineaste was put in charge of RAI’s funding and Italian cinema’s fragile revival prepared. The strength of talent finally stirring, though, means that the nation is now not just being defined by ‘the gangster’ or the maestros. Its story is being told again.

’I Am Love’ is now on release, and featured and reviewed in the May Italian Cinema special edition of Sight & Sound. ‘Vincere’ is released on May 14 and featured in the same issue. ‘Videocracy’ is released on 4 June, and both ‘Vincere’ and ‘Videocracy’ will be reviewed in the June issue of Sight & Sound. A season of recent Italian cinema runs at the Riverside, London from 16 to 25 April

Mid-August Lunch reviewed by Guido Bonsaver (September 2009)

Trastevere story: Tom Dawson interviews Mid-August Lunch’s Gianni Di Gregorio (online exclusive, September 2009)

Prince of darkness: Guido Bonsaver interviews Paolo Sorrentino about Il Divo (April 2009)

Geometry of feelings: Guido Bonsaver on L’Eclisse and Antonioni’s high modernism (July 2005)

The Consequences of Love reviewed by Philip Kemp (Film of the Month, May 2005)

Why Fellini?: Philip Kemp on il maestro’s ambivalent relationship with neorealism (August 2004)

Our friends from Turin:: David Forgacs on The Best of Youth (July 2004)

Late Fellini: A clown with wrinkles: Guido Bonsaver reconsiders the director’s late works (August 2004)

One deadly summit:: Patrick Kennedy on radical Italian film-makers undercover at the 2001 Genoa protests (September 2001)

Nights of Cabiria reviewed by Geoffrey Macnab (October 1999)

Aprile reviewed by Chris Wagstaff (April 1999)