Festivals

London Film Festival 2011: The S&S blog

The book of cult

Häxan (Witchcraft Through the Ages)

Jane Giles, 24 October

To launch the publication of 100 Cult Films (BFI Palgrave Macmillan), the London Film Festival presented a panel discussion at the BFI Southbank, illustrated with clips, about what makes a cult film. The book’s co-author Xavier Mendik appeared alongside FrightFest’s Alan Jones and myself (as former Scala cinema programmer), with film journalist Damon Wise moderating.

Arranged alphabetically from 2001: a Space Odyssey to The Wizard of Oz, Mendik and Ernest Mathijs’s accessible, scholarly guide aims to list the most influential titles from across a broad range of genres and nationalities, focusing on the films themselves rather than their context or audience. In doing so, 100 Cult Films moves the arguments on from Danny Peary’s three-volume benchmark studies Cult Movies, published in the 1980s. The panel noted that the book grapples with concerns such as whether cult films are a genre in and of themselves and if blockbusters such as Star Wars and The Sound of Music can occupy the same terrain as Debbie Does Dallas and Cannibal Holocaust (which they clearly can, as all are on the 100 Cult Films list).

The book also picks out the common elements of cult movies – transgression, abjection, freakery, utopia, ‘badness’, intertextuality, irony, and the fact that so many of them deal with themes of time (travel and ending), extreme forms of sex and violence, religious cultism, bad drug trips and midgets. But although the component parts of a cult film can be identified, any attempt to set out to make a cult film is likely to end in failure. We agreed that cult movies were both ironic and sincere.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

The panel were asked to present clips to illustrate our discussion. Jones chose a wildly camp extract from Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), the ill-advised 20th Century Fox studio film directed by the king of the cults, Russ Meyer. Mendik opted for the climax of Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) in which Leatherface performs a wild, nihilistic dance while an intended victim slowly loses her mind. Wise went for Mario Bava’s Bay of Blood aka Twitch of the Death Nerve (Ecologia del delitto, 1971), not one of the 100 Cult Films, but a giallo favourite by a key director and moreover a film with a juicy alternative title that features a highly innovative murder. After much dithering, I selected an unlikely double bill of Häxan (Benjamin Christensen, Sweden, 1922) and Café Flesh (Stephen Sayadian, USA, 1982).

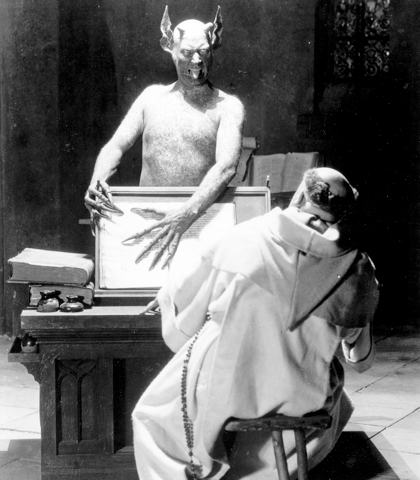

A quasi-documentary portrait of medieval devil worship, Häxan is a brilliant folly, an eye-wateringly expensive, overblown production that was so explicit and credible in its scenes of torture, nudity and ‘sexual perversion’ that it was practically unshowable, being banned or cut in many countries throughout the decades.

There were endless scenes I could have chosen, from the recreation of a Witches’ Sabbath to the Dreyer-esque trial of an accused elderly peasant, or the 20th-century hysteric in psychoanalysis, but ultimately I couldn’t resist the sequence in which the director himself pops up playing a horny devil to tempt a housewife from her conjugal bed.

I also chose to show not the tinted restoration, but the shorter, black and white 1968 release version with the narration by William S. Burroughs. This allowed me to discuss the influence of eccentric genius (and Bela Lugosi fanatic) Anthony Balch, who went from directing Kit Kat commercials to Towers Open Fire (1963), and was instrumental in London’s cutting-edge exhibition/distribution scene.

Café Flesh

Café Flesh was on my mind because it had recently shown in the Scala Forever season. I used to write about the film in my Film Studies essays, as a rich source of material with its themes of voyeurism and performance and a thundering post-apocalyptic AIDS allegory (although it was made in 1982, when the full horror of the virus had yet to reveal itself).

As creative director for Larry Flynt’s Hustler magazine, Sayadian’s movie remains the epitome of post-punk porno chic and features an electronic score by music producer Mitchell Froom (he of Crowded House albums, and ex Mr Suzanne Vega). I was pushed to find a clip that didn’t feature hardcore sex, but finally settled on the ‘skull in the cage’ speech by the film’s demented MC Max Melodramatic – the bastard offspring of Joel Grey and Henry Rollins.

Danny Peary said that cult movies are born in controversy and argument over their merits or quality, that they are “special films” (for ‘special people’! Or rather for the blessed few) that elicit a “fiery passion”. Despite the inclusion of blockbusters on the list, the panel were in agreement that the traditional definition of cult movies remains viable: these are films that are more heard about than seen.

The 1970s-80s remains the golden age of the cult movie, the moment when atmospheric big screen repertory cinemas or student film societies engaged audiences with a very wide range of films, while home video was just starting to take off and the limited number of films you could rent were particularly memorable, both because of their extreme content but also for the sheer impact on young minds of the arrival of the format in the home.

Cult films speak loudly to audiences’ imaginations – they deal in the uncanny, the spiritual and the surreal, and present an alternative that fulfils our desire to believe strongly in everything that our parents detested. What has changed is the issue of availability. The maturity of the DVD market and the accessibility of the internet give us ways of seeing everything, but small and privately. In this context, making sense of what we see becomes the real issue.

Around the world in 14 films »

See also

Revenge of the fleshpit!: Mark Pilkington remembers the Scala Cinema (August 2011)

Iván: Pedro Almodóvar remembers his late friend and director of Arrebato, Iván Zulueta (April 2011)

The Watcher in the Woods remembered by Joseph Stannard (Lost and found, March 2011)

Undead and kicking: FrightFest co-founder Alan Jones talks to Mark Pilkington (August 2010)

Messiah of Evil reviewed by Tim Lucas (January 2010)

Tarantino bites back: Quentin Tarantino talks to Nick James about Death Proof (February 2008)

Ten picks from the grindhouse: Tim Lucas’s trash top ten (June 2007)