Festivals

London Film Festival 2011: The S&S blog

Across the universe: Braden King’s HERE

Davina Quinlivan, 30 October

Following its premiere at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, Braden King’s HERE was one of the last films to be screened on the final day of the LFF, followed by a spirited Q&A with the director himself. King’s earlier, lyrical documentary Dutch Harbour: Where the Sea Breaks Its Back (1998) officially showcased his directorial vision, while his iconographic music videos for Sonic Youth, Will Oldham and the Dirty Three have served to establish his particular blend of photography, non-narrative filmmaking and visual art.

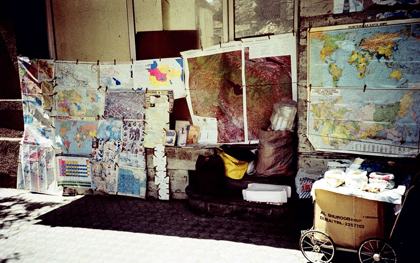

An assured fiction-feature debut, HERE is not only a synthesis of his previous work, but a bold endeavour to make a film inspired by a love of map-making and the mythology of exploration. Deliberately playing with style and genre conventions, it sets outs to map the path of love between Gadarine (Lubna Azabal), an ex-patriate Armenian and artistic photographer, and Will (Ben Foster), a Californian cartographer, as they voyage into unknown and unmapped territory in Armenia.

At the film’s core is the concept of map-making itself, or rather film experience as a kind of intimate encounter with another’s ‘map’ of time and space. Cutting across the axis of the film’s romantic drama are non-narrative intervals comprised of over-exposed, jerky, light-emblazoned images: colour-saturated polaroids here, views of Earth from outer space there. These experimental interludes are navigated and narrated by Peter Coyote, anchoring the film historically and scientifically with tales of ancient voyages and the creation of the world’s first maps.

HERE’s explicit investment in the theme of map-making, dreams and the interior lives of its protagonists may strike some viewers as exasperating whimsy (not least during those Coyote-voiced sections), but in many ways this film is an antidote to current cinema’s fascination with paranoid protagonists and detonated, hopeless landscapes. While the film is conceptually dense, the story that unfolds is subtle, sensuous and above all recognisable, in the sense that it authentically recalls what it is like to travel and be caught up in an adventure.

Crossing into the world of HERE, a line of prose appears on screen: “The story is sleeping. The story dreams.” Anticipating the ‘dream life’ of the film, as King was keen to point out during the Q&A, Here seems to knowingly channel Shakespeare’s line “We are such stuff / As dreams are made on; and our little life / is rounded with a sleep.”

This comparison between dreaming and the cinema is not a new one, but King’s methodology – experimental moving-image art, the mythic and the closely observed love affair – is genuinely rousing, imaginative and sensitively attuned to the technological potential of today’s cinema and its affirming qualities. (Von Trier’s images of the Earth in Melancholia are powerful for similar reasons.)

While much of HERE’s strength lies in its assured configuration of image and music (supplied by Michael Krassner and the Boxhead Ensemble), together with the understated performances and palpable chemistry of its two leads, King’s film- / map-making fashions an atlas out of memory and emotion in a way that makes clear the connections between geographic exploration and cinema’s unique invitation to explore everything and everyone.

Caught within the dream King sets in motion are the shadows of several other films. While a male photographer visits the ruins of churches in Armenia with his wife in Atom Egoyan’s Calendar (1993), Azabal’s Gadarine is not only a photographer but also a sort of female translator, much like Arsinée Khanjian in Egoyan’s film. Indeed, one sequence features Gadarine visiting an ancient Armenian church, filmed by British cinematographer Lol Crawley through blades of swaying grass, recalling one of the key textural motifs of Egoyan’s film. Certainly, King’s film works as an interesting counterpart to Calendar, a film more deliberately focused on questions of erotic fascination and the exotic.

There are also intertextual moments in HERE which seem to pay homage to the Armenian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov and his obsession with stillness, the wind and nature. (The crew also filmed within the Parajanov museum for the ‘transmedia’ art installation project King has also developed as a continuation of HERE’s visual language.)

Towards the end of the film, deep within the unchartered territory of the Nagorno-Karabagh region, Gadarine is seen wrapping her arms around Will’s body as he gazes at the beauty of the rural landscape they have found together. The camera tracks around the couple before insinuating itself within their embrace. Then Gadarine is seen to walk backwards, her hands slipping over, then away from Will’s chest. Beneath the surface charm and wonder of King’s poetic images is an acute awareness of the fact that we are all alone, no matter all our wildest endeavours to seek out others and to map them onto our own small islands.

They live! Treasures from the archive »

See also

The deathly hallows: Artist Mat Collishaw tells Isabel Stevens about his Retrospectre homage to the world of Sergei Parajanov (April 2010)

Out of the shadows: Ian Christie on the life and films of Sergei Parajanov (March 2010)

Ararat reviewed by Peter Matthews (May 2003)