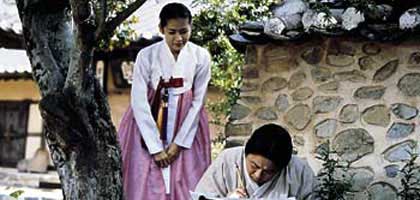

Chihwaseon Drunk on Women and Poetry

Republic of Korea 2002

Reviewed by Geoffrey Macnab

Synopsis

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

South Korea, the 1850s. Jang Seung-ub (Choi Min-sik), a young orphan, is saved by painting master Kim Byung-moon (Ahn Sung-ki) from a beating. A grateful Jang draws him a picture; Kim immediately recognises the boy's potential and becomes his mentor. Jang soon runs away. Some years later Jang renews his apprenticeship. Sent to study at the home of a Chinese nobleman, he falls for his master's sister So-woon (Son Ye-jin). She is attracted to him, but their relationship has no future because of Jang's lowly class status. He leaves and begins to hang out in bars, painting pastiches of Chinese art to make a living. These grow popular and eventually Jang is persuaded to study further at an art school run by acclaimed master Yoo-sook. His career blossoms. He meets Mae-hyang (You Ho-jeong), a noblewoman suffering hard times. He falls in love with her and paints her a screen but, she is a Catholic and is forced to flee to escape anti-Catholic persecution.

Jang's sadness is compounded by the death of So-woon. He embarks on a long journey. In his absence his work continues to be popular. On his return Kim gives him a prestigious pen name Oh-Won. Even so, he encounters hostility from artists and nobles because of his humble roots. Jang is furious to learn that one of his lovers Jin-hong (Kim Yeo-jin) has been unfaithful to him; in a drunken stupor that night he paints a monkey using his fingers instead of a brush. Frustrated with how his art is developing, he goes on the road and tries to teach himself to see the natural world in a new way. By coincidence he has a brief reunion with Mae-hyang. His fame is such that he is invited, along with other leading artists, to paint for the king. The other artists are appalled that he is allowed to make the first brush stroke, even before his master. He is taken to the king's palace to do a painting for a Chinese general, but refuses to work to order. Eventually he runs away.

During a peasants' uprising Jang is almost killed by the mob, which regards him as a parasite living off the aristocracy. Shocked, he goes on the road again, hoping to track down Mae-hyang. During his journey he meets with his master Kim, an exile now living modestly. Returning to Seoul, he has a final reunion with Mae-hyang. His health broken, he takes a job painting ceramics. Alone, he crawls into the furnace. Intertitles reveal that it is not known what finally became of Jang.

Review

Screen lives of the great artists constitute a mini-genre, one in which there are no fixed rules. Many films about painters, however, may be grouped under one of two approaches: some, such as Vincente Minnelli's Van Gogh portrait Lust for Life (1956), celebrate the artist as tortured, visionary genius, a figure who transcends his immediate social circumstances; others, notably Andrei Tarkovsky's 1966 epic about the icon painter Andrei Rublev, seek to show the era in which the artist lived. Im Kwon-taek's Chihwaseon combines elements of both approaches. It is a closely focused study of 19th-century Korean artist Jang Seung-ub a rebel from a poor background, looked down on by the art establishment; a sensualist who finds his inspiration in booze and women. But also, perhaps because there is so little now known about Jang, Im makes this outsider figure witness to some of the tumultuous events affecting Korean society at the time.

Chihwaseon offers an impressionistic, if slightly confusing account of the key moments in Jang's life, from his childhood to his eventual success. Throughout Im touches obliquely on the social and political chaos of late-19th-century Korea, as peasants revolt, Catholics are persecuted and the Japanese threaten invasion. None of this turbulence finds its way directly into Jang's exquisite paintings of birds, trees and flowers, but we're always made aware of the context in which he is working. In one scene we see him being beaten up because he has refused to kneel in the presence of an aristocrat; in another he is sneered at by peasants as a lackey of the old regime. He is a paradoxical figure: driven and ambitious, but so little interested in worldly success that he often gives away his most elaborate and ambitious paintings. Choi Min-sik plays him as a man of huge curiosity and voracious appetites, with a Rabelaisian zest slightly reminiscent of Toshiro Mifune.

Some commentators have described Chihwaseon as a companion piece to Im's 2000 feature Chunhyang. In terms of the lavish production design, period detail and close attention Im pays to the natural world, there are obvious overlaps. A love story set in the 18th century, Chunhyang has a narrative structure every bit as elliptical as that of its successor. (It is 'narrated' by a balladeer, singing out the story to a contemporary audience.) Again, Im takes what seems like a piece of folklore and uses it to make trenchant points about class, oppression and the relations between the sexes. However, Chihwaseon for all the zest of the central performance is a darker, more melancholy affair. By focusing so intently on the restless perfectionism of his artist protagonist, Im allows little room for the upbeat romanticism which characterises the earlier film.

Showing painters at work is obviously central to any artist biopic, but there's a risk that such a delicate, painstaking process can seem boring or ridiculous when depicted on screen (Ed Harris acknowledged as much when discussing his film Pollock). Im has no qualms about including frequent shots of Jang painting, and these prove to be among the most richly involving sequences in the film. Often the first brush strokes will be thick, seemingly clumsy, but these will give way to extraordinarily delicate renderings of the natural world. There's a sense of mirroring and of competition throughout, with Im and his virtuoso cinematographer Jung Il-sung trying to match Jang's work with the images they capture on film. There's an astonishing sequence in which we see a flock of thousands of birds swooping through the sky before being shown Jang's rendition of it.

There are obvious flaws in the narrative structure: certain characters most notably the different women with whom Jang becomes entangled enter his life in disconcertingly abrupt fashion. Im introduces various sub-plots for instance, the anti-Catholic persecution and peasants' revolt without elaborating the effect they had on society as a whole. The stated parallels between Im's struggles as a film-maker and Jang's as an artist are also likely to be lost on western audiences, for whom both Im and Jang are little-known figures. Nonetheless, this is a fascinating, consummately crafted and ultimately moving study of a man who conforms surprisingly closely to western archetypes of the artist as rebel and hedonist.

Credits

- Director

- Im Kwon-taek

- Producer

- Lee Tae-won

- Screenplay

- Kim Young-oak

- Im Kwon-taek

- Kang Hea-yun

- Director of Photography

- Jung Il-sung

- Editor

- Park Soon-duk

- Production Designer

- Ju Byoung-do

- Music

- Kim Young-dong