Primary navigation

UK/US 2006

Reviewed by Nick James

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

A documentary that sets out to unravel the enigma surrounding former pop idol, rock god and now avant-garde song composer Scott Walker. With an exclusive new interview with Walker to frame itself around, the film looks back from the studio sessions for his 2006 album The Drift to his Californian youth. He first made records under his real name, Scott Engel, in the late 1950s. In the early 1960s he played bass and sang backing vocals in the nascent Walker Brothers, who were then lured to 'swinging' London where they had huge success after Scott reluctantly took over the role of lead singer. Encouraged to write songs for B-sides, his left-field tastes found him innovating songs of poetic mystery that eventually lost him favour with the public. Various interviewees contextualise the shifts in his career, set alongside Walker's own reminiscences.

The ironies of Scott Walker's career as a pop idol, crooner, poetic songwriter and composer are so rich as to seem genuinely magical. Documentary director Stephen Kijak - formerly best known for the extraordinary study of New York film obsessives Cinemania - understands this completely. He knows that a cool presentation and juxtaposition of the facts and opinions in a tight order is his most effective means of letting the contradictions speak for themselves. But the ironies are not even the chief joy of this reverie-cum-tribute. For just when you think the arc of Walker's fame-to-obscurity narrative - how he went, that is, from pop hits like 'The Sun Ain't Gonna Shine Anymore' to such self-penned introspections as 'Montague Terrace (in Blue)' - is tied in a neat package, just when you're sure we're about to knuckle down to the difficulty of Walker's late avant-garde work in all its agonised reaching, Kijak diverts us with a sidestep of winning charm. Using the mini-story of Walker's revived esteem among younger musicians in the 1980s through The Teardrop Explodes singer Julian Cope's advocacy as its prompt, the film catches various commentators - Jarvis Cocker, Damon Albarn, Alison Goldfrapp et al - as they listen to, and are often visibly shaken by, Walker's music. The emotions here are so exposed you would have to be allergic to every aspect of Walker's singing not to experience at least a wobble of empathy. Remembering that existential symphony of the melancholy modern self that is a Scott Walker song gives us pause, as if all other rock music should somehow be ashamed of itself for being so unambitious.

Chief of the Walker ironies is that in his younger days he was a walking postmodern contradiction of a kind that's unimaginable today: a drop-dead handsome lead singer of a boy-band who just happened to have a beatnik existentialist's taste in films and music. Hence he was bemused in Paris when everyone only wanted to talk about Hollywood movies instead of French ones. As a guest on the Frankie Howerd show he would sing, not some MOR 'housewife's choice' number like 'Joanna', but Jacques Brel's scabrous Brussels street ballad 'Jackie'. Here that irony is compounded when Walker tells us that he was introduced to Brel's songs - Mort Shuman's English translations of which became central to Walker's transformation into a songwriter - by a Playboy bunny girl he picked up at the Playboy Club's opening-night party in London. His own songwriting only came about because the Walker Brothers' manager urged them to write songs for B-sides in order to get publishing royalties. Scott Walker found himself a fledgling writer with a full armoury of arrangers and orchestras to work with, so that if he said "I hear Debussy here" that's what he got. But the thing is, he did know his Debussy.

The film's only flaw is that it comes down so firmly on the side of snobbery. It doesn't allow that the adult musical and lyrical sophistication of the light, jazzy pop songs of the 60s that Walker sometimes sang - such as Burt Bacharach's - often makes them just as complex in their way as Walker's own stentorian curiosities. But then the film does have to deal, eventually, with the later work, which is far more of an acquired taste than the hall of anguished mirrors that is Scott 4, the album that lost him his pop constituency.

For this reviewer, Walker's late work had to be a question of advocacy, since I didn't know much of it. Again Kijack's film rises to the task. We find ourselves with Brian Eno, listening to tracks from the Walker Brothers' one-off reformation album Nite Flights. They recorded it knowing the company was going bust, so Scott Walker used the opportunity to write out-there songs which cause Eno to wilt with despair that music since then hasn't gotten any further. David Bowie (the film's executive producer) was working with Eno at the time and they both admit to the album's influence on what they were doing. For Walker, though, it was just the beginning of a career as a serious composer of songs that are closer to tone poems and noise than to anything the charts have ever listed.

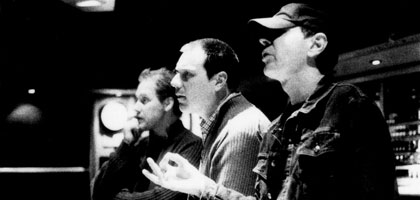

Seeing the Walker of today, who uses the brim of his baseball cap to avoid eye contact until he really gets to know you, the haunted quality of his looks is more pronounced. The music he makes now suits his spotlight-shunning, hypersensitive nature. Whatever his demons might be, he is true to his notion of art, and rather than make sense of him, this documentary thrillingly compounds his mythology.