Primary navigation

Two actors ruled the jungle after Johnny Weissmuller handed in his loincloth. Tim Lucas on the ape men

In March 2009, Warner Home Video responded to conflicting consumer demand and sagging DVD sales in a revolutionary manner. The company launched the Warner Archive Collection, a series of unrestored, no-frills web exclusives available from WBshop.com as $14.95 downloads or as $19.95 DVDs. These are not DVD-R discs as sometimes rumoured; they are NTSC, region-free, ‘play only’ discs in simple yet specific packaging, meant to work in ‘play only’ devices, although (the packaging states) they “may not play back in [certain] recorders and PC drives.” (I haven’t had trouble with either, and should also add that the titles are anamorphically enhanced when appropriate.) Warner Archive doesn’t fulfill individual requests for vault items, but it does issue new titles regularly, with its present inventory encompassing such worthwhile items as Roy Rowland’s poignant Our Vines Have Tender Grapes, Joseph Losey’s anti-conformity parable The Boy with Green Hair, and multi-disc sets devoted to the ‘Our Gang’ comedies.

Of particular interest is a series of 11 individual titles that continue the serial saga of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan the Ape Man from the moment ageing Olympic swimmer Johnny Weissmuller hung up his loincloth to become Jungle Jim. Inheriting his mantle (and chimp) for five films was Lex Barker, a naturally impressive physical specimen who went on to 1960s stardom in West Germany, while a further six starred the first bodybuilder Tarzan, Gordon Scott.

At their best, the Weissmuller Tarzan films struck a perfect balance between escapist romance and pulp jungle thrills – something for the ladies and something for the gentlemen. As the series passed from MGM to RKO and producer Sol Lesser, it fell under the ever-tightening strictures of the Hays Office and had to downplay the return-to-Eden fantasy enacted by Tarzan and Jane (Maureen O’Sullivan, followed by Brenda Joyce) in favour of Dorothy Lamour-like exotica and tribal pageantry. Lex Barker’s five Tarzan films are unquestionably troubled – it doesn’t help that he acts opposite a different Jane in each one – but that’s not to say they aren’t fun, and sometimes more. The first intelligent screen Tarzan, Barker was the actor closest to the image purveyed by artists Burne Hogarth and Hal Foster; visually, four of his five films benefit from the cinematography of Karl Struss (Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross); and they are directed by solid B-craftsmen such as Byron Haskin and Cy Endfield, working from scripts by the likes of Curt Siodmak (I Walked with a Zombie) and Cyril Hume, whose mostly unsung but impressive CV includes Tarzan the Ape Man, Weissmuller pinnacle Tarzan Escapes and Forbidden Planet.

The mistakes made in Barker’s first, Tarzan’s Magic Fountain (1949), including an embarrassing pair of slippers for the tenderfooted jungle lord and too much comedy relief from Cheeta, are all fixed in the second, Tarzan and the Slave Girl (1950), which benefits from the sultry Denise Darcel, who catfights Vanessa Brown’s Jane. Tarzan’s Peril (1951), featuring George Macready as a menacing gun-runner as well as distinguished African-American thesps Dorothy Dandridge and Frederick O’Neal, was the first Tarzan film to shoot on location in Africa, but this stab at authenticity sometimes deadens the jungle fantasy. Again, the series learned from its past missteps: in Tarzan’s Savage Fury (1952), Hume’s family-themed script not only brings the character back to his Greystoke roots, with the introduction of a murdered cousin, but back to his MGM roots by emphasising Tarzan’s romance with Jane (the overly movie-starrish Dorothy Hart) and the jungle education of a newly adopted son (Tommy Carlton) who is absent without explanation from the next picture. Tarzan and the She Devil (1953), the most consistent of the series if not the most ambitious, pits Barker against smug, big-gutted ivory hunter Raymond Burr and his slinky financer Monique Van Vooren, who abduct Jane (Joyce MacKenzie, Barker’s best match) and burn down Tarzan’s treehouse in the process, so that he thinks her dead and loses his will to survive.

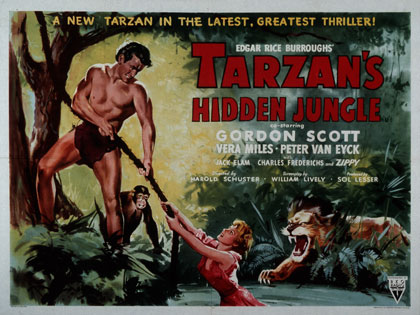

Jane is out of the picture in Gordon Scott’s debut, Tarzan’s Hidden Jungle (1955), the last of Lesser’s RKO pictures and notable only for a gorgeous Vera Miles, who married her Tarzan during production. Lesser then became a free agent, joining forces with British producers John Croydon and N. Peter Rathvon for the pleasing Tarzan and the Lost Safari (1957), the first Tarzan in colour, featuring a solid cast including Betta St John and George Coulouris. The unfortunate Tarzan and the Trappers (1958) is back to black-and-white, a feature version of an ill-fated television series project that saddles Scott with a suddenly-there Jane (Eve Brent) and Boy (Rickie Sorensen). They return in the slightly better colour feature Tarzan’s Fight for Life (1958), with Boy now called Tartu, but it is the next two pictures, made by producer Sy Weintraub following Sol Lesser’s retirement, that exonerate the Gordon Scott period.

Directed by John Guillermin, with Nicolas Roeg acting as camera operator, Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure (1959) reboots the franchise in the same way that Casino Royale did with the Bond films (a convenient analogy, given Sean Connery’s presence in a meaty early role). Working from a script finally pitched at adult audiences, Scott rises admirably to the occasion of acting opposite Anthony Quayle and Niall MacGinnis, scores his most valid screen relationship with Sara Shane, and carries the film to the most exciting climax of the entire series. Robert Day’s Tarzan the Magnificent (1960) is nearly as invigorating, with Tarzan asked to escort killer Coy Banton (Jock Mahoney) to justice – a task complicated by a group of stranded travellers he must protect, and the deadly tracking of Coy’s deranged kin.

The Scott films aren’t yet available as downloads, but WBshop.com is currently offering the Barker and Scott collections at a 50 per cent reduction.

Tarzan (Chris Buck & Kevin Lima, 1999) reviewed by Leslie Felperin (November 1999)