Review / From the archives

Before the Revolution

Bernardo Bertolucci’s second feature eyes the brief flickering of a young bourgeois’ revolutionary ardour in the director’s Parma hometown. Philip Strick admires his command, in this original 1969 Monthly Film Bulletin review

Before the Revolution

Italy 1964

Director: Bernardo Bertolucci

With Adriana Asti, Francesco Barilli, Allen Midgette, Morando Morandini, Domenico Alpi, Cristina Pariset, Emilia Borgi

112 mins

Synopsis

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

At the age of twenty, Fabrizio has fallen under the spell of Marxist ideology and makes fervent plans to wipe out the comfortable stagnation of the middle classes as represented both by his own background and that of his fiancée Clelia. He has two allies: Cesare, a schoolteacher, and Agostino, the attractively crazy young son of a prosperous manufacturer.

His first act of revolution is to break with Clelia, much to the disappointment of his parents, who promptly invite his young aunt, Gina, to stay for a while in the hope that she will be better able than they to communicate with their delinquent son. Fabrizio takes little notice of her until Agostino is suddenly drowned and his death leaves Fabrizio lost for a close friend; in talking to Gina about the greatness of Agostino, he becomes drawn to his aunt, who warmly returns his interest, and they soon become lovers.

Gina is an unstable and neurotic woman, and in trying to cope with her moods Fabrizio matures very quickly. One day he sees her emerge from a hotel with a man she has met in the street, and his blind bitterness at this encounter causes a rapid deterioration in their relationship; finally it is Cesare who helps her with her suitcases back to the station and she returns home to Milan. Depressed, Fabrizio returns to Clelia, the uncomplicated and beautiful girl who, like the way of life she represents, is so easy for him to settle for.

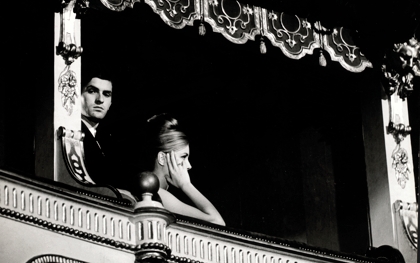

Visiting the Opera with her some months later, he unexpectedly runs into Gina again and finds that her fascination is still strong; but Gina leads him firmly back to Clelia. As Fabrizio and Clelia are married, Cesare preaches to a new generation of schoolchildren and Gina tearfully clutches Fabrizio’s younger brother.

Review

Unavoidably, of course, one links the names of Bertolucci and Pasolini, the latter, on the basis of sheer output and experience, being the greater so far. What was astounding about the disciple’s first film, however, continues to be enthralling in Before the Revolution – the fact that he can both overstate and understate and get away with either nearly every time. With the opening scenes of the film one could swear that it will never make sense, so curt is Bertolucci’s shorthand: a quote from Talleyrand, a diatribe against Catholicism, a bumping, urgent close-up of Fabrizio running, the briefest of magical panning shots with the docile Clelia, and shot upon shot of Agostino falling off his bicycle – the images, the landscapes, the statements come pouring out in a flood.

And then with the arrival of Gina and the beautifully held shots of Fabrizio’s parents painstakingly doing nothing at all, the explosive pieces start to drop easily into place. Agostino of the feathery hair and sensible and utterly impractical schemes he represents, and the marching song of Fabrizio’s revolt fades into the stiff breeze of another kind of passion. One can’t remember Pasolini’s anger ever taking this kind of direction (Accatone, for instance, was not the type to be bowled over by his many girlfriends), but Bertolucci’s possibly unconscious dilution by the influences of popular cinema, with Red River neatly giving way to Une Femme est Une Femme, has a complicity to it that fully matches the Pasolini dialectic.

Gina is an astonishing creation in all her seductive anguish; her scene with the stridently singing girl is a totally disorientating situation, even if none too well edited or dubbed, while the compulsive collection of a copy of every magazine in a newsagent’s and the furiously desolate telephone call to an unknown (to us) psychiatrist in the middle of the night are bold brushstrokes that fill out insanity before our eyes. Unfair, perhaps, to dash Fabrizio’s aspirations on the irrational ravings of a nymphomaniac, but one might just as well insist that we should have been present for Cesare’s teaching (surely he didn’t spend all his time quoting from Melville?) or at Agostino’s death. Both are graphically enough described, and what matters is their effect on Fabrizio; like all the middle-class – and in Bertolucci’s hands, Parma, his own home-town, seems to become the definitive bourgeois stronghold – he finds himself absolutely disorientated when he tries either to be more sophisticated or to be more primitive.

Far better to settle for the cool elegance of Clelia, who has the additional merit of being silent, and attend to the simple storyline and establishment composition of Verdi’s ‘Macbeth’. In that China is Near forecasts a similar process of erosion rather than of overnight salvation, it would seem that the new generation of Italian filmmakers are irritable Fabrizios to the life. “I thought I was living the Revolution,” he says gloomily, “but they turned out to be the years before the Revolution. For my sort they always are.” And Bertolucci has the sense to poke fun at this, too, with his ending: Cesare churning out the doctrine all over again to his new band of fidgeting pupils, Gina emoting over the curly head of the next Fabrizio in the line (it’s a nice touch to trick us into thinking that it actually is Fabrizio when we first see the shot), while the happily married couple drives away in a smooth and altogether right-wing limousine. The style, the narrative and the message may not be particularly revolutionary in themselves, but Bertolucci as a director with enormous promise is still in there, pitching away.

Philip Strick, Monthly Film Bulletin, April 1969

‘Before the Revolution’ is re-released at the BFI Southbank and around the UK from 8 April 2011

See also

Just like starting over: Tony Rayns on Bertolucci’s emergence from the influences of Pasolini and Godard (May 2011)

The killer inside: David Thomson on The Conformist (March 2008)

The Dreamers reviewed by Ginette Vincendeau (February 2004)

Bernardo Bertolucci’s top ten films (2002)

Besieged reviewed by Sally Chatsworth (May 1999)