Primary navigation

To mark a comprehensive Bertolucci retrospective, Tony Rayns looks back at the early 1960s, when the great Italian director hit his stride and emerged from the shadow of his mentors, Pasolini and Godard

There must be an elegant way of summing up a moment of transition in a film culture – a moment when a new spirit or attitude asserts itself – but I haven’t found it. The mission I rashly chose to accept was to look back 50 years to the arrival of Bernardo Bertolucci on the Italian film scene, and to examine how he came to terms with influences from two disparate spiritual mentors, Pier Paolo Pasolini in Rome and Jean-Luc Godard in Paris. Easier said than done: even without the gargoyle of Berlusconi to muddy everyone’s view of Italian culture and politics, it’s a daunting challenge to get a fix on the time when the young Bertolucci emerged. Factors in play include the political uncertainties of Italy’s post-war recovery (the residual taint of fascism), the way that regionalism and factionalism prevailed (running counter to the image of Italian unity), the disputatious intellectual climate of the day and the surprising developments in Italian pop-genre cinema in the 1960s (horror movies, muscle-queen exotica, westerns) – all on top of Bertolucci’s own desire to establish a distinctive voice of his own.

By contrast, the biographical facts are pretty easy. Bertolucci was born in Parma in 1941, son of the poet/critic Attilio Bertolucci, who numbered Cesare Zavattini (writer of De Sica’s most famous movies) among his former pupils – and, later, the gay poet/novelist/screenwriter Pier Paolo Pasolini among his friends. The young Bertolucci showed the symptoms of precocious cinephilia: he shot small movies in his early teens with family and friends, while avid cinemagoing equipped him for his later work on the screenplay for Leone’s Once upon a Time in the West (1968), where he and movie-buff Dario Argento (born 1943) pooled their memories of archetypal western plots and motifs.

The Bertolucci family moved to Rome in the late 1950s, and when Pasolini turned director in 1961 to make Accattone, Attilio asked his friend to hire his 21-year-old film-mad son as an assistant director. Bernardo Bertolucci has always described the experience of working on Accattone as his film school, and his association with Pasolini (who had already dedicated poems to the young man) led directly to the opportunity to direct his own debut feature the following year.

Our present-day sense of Italian cinema in the 1950s, shaped by what’s available on DVD, is defined by the work of the major directors: Rossellini, Visconti, Antonioni and Fellini, none of them much given to genre movies, and all with roots in the neorealist aesthetics of the late 1940s. It’s obvious enough that none of them felt limited or constrained by the tenets of neo-realism – their 1950s films are equally rooted in whatever else engaged them, from melodrama and sentimentality to Catholicism and opera. But it’s also clear from the 1960 films La dolce vita (Fellini) and Rocco and His Brothers (Visconti) that neorealism remained an important element in their work.

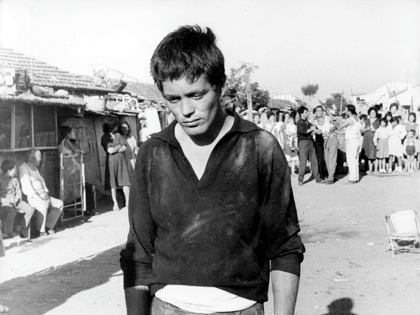

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Accattone

Pasolini’s street-life novels of the 1950s were also marked by neorealist impulses – specifically, a fascination with the virility of young working-class men – and it was this aesthetic/sexual orientation that smoothed his way into film circles. Fellini was one of the first to seek his help (Pasolini worked on the script for Nights of Cabiria in 1956), while Pasolini’s five-film collaboration with director Mauro Bolognini in the late 1950s included an adaptation of his own novel Ragazzi di vita under the title Le notte brava in 1959.

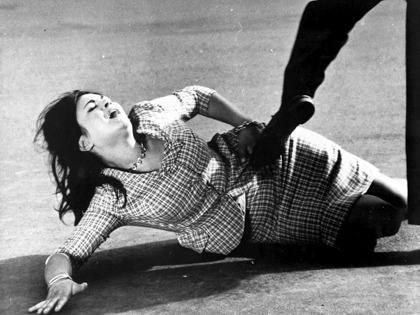

Thematically, Pasolini’s own Accattone picks up where the Bolognini films left off: with a homoerotic focus on male bonding and rivalry between street toughs, plus more ruminations on the resilience and psychological dependency of the girlfriends forced into prostitution. But from the opening plangencies of Bach on the soundtrack, Accattone committedly redefines the neorealist aesthetic. Pasolini’s filmmaking is marked from the very start by his argument that cinema can be either ‘prose’ or ‘poetry,’ and his clearly sets out to be poetic.

Pasolini’s poetry doesn’t in itself mark a radical break with the Italian cinema that preceded it, and no one thinks of Pasolini as the progenitor of an elusive Italian ‘new wave’. On the contrary, Pasolini seems always sui generis, while the impulse to sweep away old culture and start afresh stems from what was happening in French cinema in 1959/60. As a bright, poetically inclined cinephile in his early twenties, Bertolucci was naturally entranced by the nouvelle vague, and most particularly by Godard’s A bout de souffle (Breathless, 1959), with its blend of informality and gravity, its out-of-control cinephilia and its liberating jump cuts – not to mention its amoral closeness to a charming, cop-killing sociopath. So it’s not surprising that references and homages to Godard soon turn up in Bertolucci’s work when he becomes a director. It’s more interesting that graduating from the ‘film school’ of Accattone helped to prevent the young filmmaker from morphing into an Italian Godard.

The Grim Reaper

Bertolucci inherited The Grim Reaper (La commare secca, 1962) from Pasolini, who had intended it as his own debut feature before turning his attention to Accattone. The producer Antonio Cervi acquired the project, hoping that Pasolini himself would return to it, and offered it to the younger man when Pasolini went on to make Mamma Roma. Bertolucci collaborated on the shooting script with another graduate from Accattone, Sergio Citti. The film is framed as an investigation into the murder of a prostitute in a park at night, but Pasolini seems to have conceived it as the antithesis of a giallo thriller, and Bertolucci’s reworking of the script removes whatever traces of mystery or suspense may have been left in the original. The structure is episodic: an unseen cop questions a succession of men who were in the park that night, each testimony contributing to a broad picture of the various interactions and transactions that took place. (A gay cruising element is present, of course, but somewhat muffled in Bertolucci’s treatment.) There’s no misdirection or deduction involved, just a process of gradual revelation. The film is interspersed with images of the prostitute’s last hours of life, unrelated to the testimonies: woken by a downpour, she prepares to go out in search of a client.

In one way, this is all still very Pasolinian. Bertolucci takes up Pasolini’s visual syntax of formalised static portraits and panning shots, adding only the tracking shots, which Pasolini would have avoided; he also echoes Accattone’s patterns of repetition and variation. Equally, most of the characters and settings could have come straight from Accattone. What isn’t Pasolinian is the absence of a central protagonist, the absence of an imposed ‘sacred’ dimension of the kind provided by Bach, and the general sense that young people are aimless and unformed.

It’s the last of these that looks forward to Bertolucci’s next two features. Because of the casting, the most striking episode in The Grim Reaper is the one about Teodoro, a soldier on leave – he’s played by Allen Midgette, who also appears in small but crucial roles in Before the Revolution (1964) and The Spider’s Stratagem (La strategia del ragno, 1970). (Midgette was the man later hired by Andy Warhol to impersonate him on a lecture tour; he acts in Warhol’s Nude Restaurant and Lonesome Cowboys, and even puts in an appearance in the Godard/Dziga Vertov Group Vent d’est.)

Before the Revolution

Bertolucci’s second feature Before the Revolution (Prima della rivoluzione) is generally thought of as the movie in which he found his own voice. Everyone who has ever commented on it makes much of the director’s admission that it’s crammed with autobiographical resonances, even though it’s notionally modelled on Stendhal’s 1839 novel The Charterhouse of Parma – and spiked with homages to favourite films and filmmakers. But if we take the protagonist Fabrizio (played by Francesco Barilli) as a self-portrait, it’s a remarkably unflattering one. Fabrizio spends most of the movie jilting his pretty but dull fiancée Clelia (Cristina Pariset), in order to pursue a quasi-incestuous liaison with his emotionally unstable aunt Gina (Adriana Asti from Accattone, Bertolucci’s real-life partner at the time); when he finally marries Clelia in the closing scenes, it signals an abandonment of his rebellious impulses and a passive acceptance of bourgeois conformity. Although it features a scene at a Communist Party fair, neither the film nor Fabrizio himself has any defined political thrust; the final capitulation to bourgeois values makes the title doubly ironic.

Bertolucci pays homage to Godard (Fabrizio goes to see Une femme est une femme and then sits down in a café to discuss screen heroines) and to Pasolini (Fabrizio denounces the unholy bond between church and state). But the overall emphasis on individual psychology prevents Before the Revolution from feeling either Godardian or Pasolinian – although both directors are sometimes evoked in the frequent close-ups of faces. The autobiographical aspects, rooted in the settings and the reflections on cinema (the two come together in a sequence in the camera obscura in Fontanellato) in fact anticipate Bertolucci’s later immersion in psychoanalysis, not to mention the divided self at the centre of his third feature Partner (1968). The unflattering similarities between Fabrizio and Bertolucci himself bespeak a palpable desire to externalise and exorcise the aspects of his own psyche that he fears and distrusts.

It’s therefore curiously fitting that the film is both lyrical and disjointed; its stylistic jolts have no parallel in the film with which it’s often bracketed, Marco Bellocchio’s Fists in the Pocket (1965), another dysfunctional family romance that uses a Verdi opera to underline its climactic turning-point.

After those first two features, Bertolucci loosened up. His next two fictions, the short Agonia (shot in 1967 but released in the omnibus Amore e rabbia / Love and Anger, 1969) and the feature Partner are both founded on theatre, but only as a way of giving their content a Brechtian objectivity, while freeing the director to explore ideas of cinema. Agonia, a collaboration with Julian Beck and Judith Malina’s Living Theater, is a sardonic parable about the death of god and the manias of mankind, aggressively shot and cut. Partner, inspired by Dostoevsky’s The Double, is about a timid, academic drama teacher who encounters or imagines his own doppelgänger (both played by Pierre Clémenti) and watches as the double tries to foment revolution with his students.

Partner

Partner seeks to include everything from the Vietnam War to soap-powder advertising – and respects nothing. The teacher Jacob is flaky from the start (in the opening scene, perusing Lotte Eisner’s book on Murnau in a coffee shop, he imagines shooting the neighbour whose piano-playing has disturbed him) and the best joke in a film full of droll inventions is the increasing interchangeability of Jacob I and Jacob II: in later scenes, it’s often impossible to tell which one we’re watching.

Partner is frequently described as Bertolucci’s ‘most Godardian’ film, but it disses Godard along with everything else, and anyway has a breadth of reference unmatched in any Godard movie. Bertolucci reports that Clémenti made regular trips back to the riot-torn streets of Paris during the shoot, returning each time with new slogans and ideas to be incorporated in the film – which is no doubt why the result feels closer to the Belgian situationist writer Raoul Vaneigem than it does to Godardian cinema. Like Before the Revolution, though, it is a story of defeat – of bourgeois norms reasserting themselves and prevailing. (Jacob I even has a pretty, brainless fiancée, just as Fabrizio had, but Jacob imagines doing away with her on a streetcar named desire, and ends up alone with his double.) It’s not until he makes The Conformist (Il conformista, 1970) and The Spider’s Stratagem that Bertolucci finds more insidious and less confrontational ways of undermining the middle-class consensus. But that’s another story.

In Partner’s most notorious scene, Jacob II shows the drama students how to make a Molotov cocktail. It’s a bomb that the film itself cannot detonate, but the film certainly succeeds in lighting the blue touch-paper under Bertolucci’s two artistic mentors – this is the film in which he shakes off influences and becomes his own man, however contradictory and divided he may be.

Just before the revolutionary act that is fated to fail, Jacob I eagerly asks Jacob II how events will play out. It will begin and end in theatre, says Jacob II. “Theatre!” they call to each other, exultantly – until Bertolucci’s own voice whispers on the soundtrack: “Cinema!” A shining example to us all.

‘Before the Revolution’ is rereleased on 7 April. A Bertolucci retrospective plays at BFI Southbank, London until the end of May. ‘The Grim Reaper’ released on DVD by Mr Bongo on 25 April

Maestros and mobsters: Nick Hasted on a new generation of Italian filmmakers emerging from the legacy of cinematic nostalgia and political corruption (May 2010)

The killer inside: David Thomson on The Conformist (March 2008)

The Dreamers reviewed by Ginette Vincendeau (February 2004)

Bernardo Bertolucci’s top ten films (2002)

Paris match: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith on the post-war Parisian ferment that produced Jean-Luc Godard, Cahiers de cinema and the French New Wave (June 2001)

Besieged reviewed by Sally Chatsworth (May 1999)