The Gilbert Adair files

Favourites

Editor’s note:

Some of Gilbert Adair’s favourite artists are celebrated here: Jean Cocteau, Jean-Marie Straub, Danièle Huillet and Robert Bresson. The first piece, on Antonioni’s now largely forgotten Il Mistero di Oberwald, includes what were then far-sighted reflections on the cinema’s move towards electronically-generated imagery, while the review of Straub/Huillet’s Kafka adaptation Class Relations delves into questions of filmic and indeed critical style. The Bresson piece originated as a news item celebrating the discovery of his long-thought-lost slapstick comedy short (!), Les Affaires Publiques – but its vivid description of the film itself is doubly valuable given its continued inaccessibility.

— Michael Brooke

The Eagle Has Three Heads: Il Mistero di Oberwald

Reviewed in Sight & Sound Autumn 1981, page 276

As rarely, critical opinion on Il Mistero di Oberwald (Artificial Eye) has remained undivided since its frosty reception at the Venice Festival in 1980. By well-nigh universal consent, the film founders on three colossal mismatchings: Antonioni/Cocteau, Antonioni/video and video/Cocteau, each of them edgily stalking the other two as in the vicious triangle of a Sergio Leone shootout. Nothing, in fact, could better serve as the heading for an unsympathetic review than the title of the western I’m alluding to, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: a good director (Antonioni), having encumbered himself with a bad play (L’Aigle a deux têtes), perversely undermines it still further with an ugly electronic process (video). Since this is intended to be a basically sympathetic review, and since the film would be unlikely to receive too much attention did not its director’s past achievements justify interest in anything he does, I take the liberty of assuming as a given the first of these postulates. But what of the others?

L’Aigle a deux têtes was reputedly written at the request of Jean Marais, who craved a role that would give him the opportunity to “remain silent in the first act, weep with joy in the second, and fall downstairs in the third”. What Cocteau, a professional to his elegantly tapering fingertips, came up with was – depending on how attuned one is to his feverish imaginative world – either a flamboyantly Hugolian melodrama or Sardou with a lisp. Inspired by the myths shrouding the deaths of Ludwig n of Bavaria and the Empress Elisabeth of Austria, he ‘concocteaued’ an apocryphal enigma of his own – in the library of her crag-perched hunting lodge, a widowed Queen is discovered with a dagger in her back while a young anarchist poet, the image of the dead King, agonises at the foot of the staircase – then proceeded to write a play that would resolve it. If its plot is an insult to the intelligence, it is a deliberate, calculated insult; the paradox of it is that only by pulling all the stops out, by virtually courting disaster, can disaster be skirted. In a recent Chichester revival, Jill Bennett provoked incredulous giggles after her stabbing by fingering the small of her back as ineffectually as if her bra strap had got twisted.

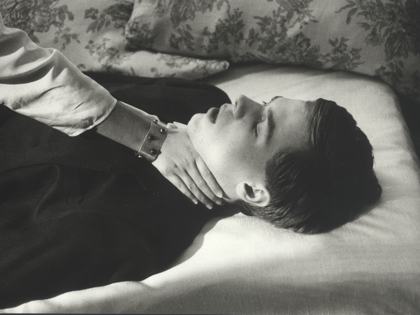

The strength, as also the crippling weakness, of Antonioni’s adaptation is that the intelligence which delivers him from that particular trap is the same that disqualifies him from seriously coming to terms with a work in which hyperbole is the common coin and anything less than the grand gesture constitutes a breach of etiquette. To be sure, both Monica Vitti and Franco Branciaroli (who bears a striking resemblance to the aforementioned Ludwig) look perfect, the latter renouncing Marais’ Tyrolean lederhosen in favour of a revolutionary’s worn corduroy (a visual pun here: corps du roi?) – a relatively minor detail, perhaps, but one symptomatic of Antonioni’s taste and discretion. As is the fact that the screenplay has been shorn of a few of Cocteau’s gold lamé excrescences: the dénouement, for example, treads a wary path between delirium and sweet reason by having Stanislas (renamed Sebastian for the film) simply shoot the Queen, then in his death throes stretch out his hand towards hers in a pose immortalised by another Michelangelo. But in the play’s preface Cocteau defines his characters’ psychology as ‘heraldic’, and the insignia of that heraldry are precisely the assassin’s lederhosen, the Queen’s insistently snapping fans, the candelabra à la Liberace. With commendable restraint Antonioni selected passages from Brahms, Schoenberg and Richard Strauss as background music, yet the more obvious Liebestod, however hackneyed from overuse, would also have been more apt; he and Tonino Guerra considerably abridged the Queen’s marathon 19-minute monologue, yet it’s a speech that only becomes effective the moment one begins to steal glances at one’s watch; and though the doomed lovers ought to be working up a storm fit to rival the thunder and lightning raging outside the window, Vitti is a strangely muted monstre sacre and Branciaroli a cypher (the role might have been – and, in other circumstances, probably would have been – written for Helmut Berger).

What is regrettable about such ‘excess in moderation’, as it were, is that Antonioni’s visuals (shot with a video camera, then transferred on to 35mm film) are certainly a match for Cocteau’s textual extravagance. Mine is a minority opinion, but I am convinced that his experiments with video and colour will make Il Mistero di Oberwald the Becky Sharp of cinema’s long-promised and long-deferred electronic era. Since, at this primitive stage of its development, a video image cannot compete with the seamless fabric of light and shadow spun by a great cinematographer, Antonioni has chosen to accentuate, rather than attempt to mask, the medium’s fragmented, honeycombed textures, so disturbing to the conditioned film buff. If Il Mistero’s literally dazzling landscapes, its baleful moon, the spectral chiaroscuro of its interiors (evoking, appropriately enough for such melodramatic silent film material, early essays in two-strip Technicolor) may be termed ‘painterly’, then it’s in the strictly theoretical sense of being no longer the two-dimensional imprints of a glamorous three-dimensional studio set. Here ‘beauty’ (and there seems no reason why video should forfeit any of the charms of traditional cinema) is something that is adjusted on a control panel – so much so that only a photogram, not a set photographer’s still, can give one the slightest clue to the film’s ‘look’. Such effects as the cold pastillised green with which the screen is suffused during a squabble between two mutually jealous courtiers and the clouds of mauve glory trailed by the scheming chief of police when he enters the Queen’s library allow the cinema for the first time in its history to lay claim to ‘lighting’ as rich and expressive as in the theatre. And if these examples appear pedantic or simple-minded, it should be said that the colours are more often deployed abstractly, even musically – almost as a suite of leitmotiven.

It would be vain to pretend that the results are anything but imperfect. But in view of the immense potential that the film opens up (for Antonioni has clearly understood that, like sound, colour, CinemaScope and 70mm, video is not only a technical process but an aesthetics), its easy, not to say snide, dismissal by the critical establishment makes for disheartening reading.

Amerikana: Class Relations

Reviewed in Sight & Sound Spring 1985, pages 144-145

The beauty of a ‘style’ – literary, musical, cinematic, whatever – is analogous to that of a face in love-making. One’s attention may increasingly be solicited elsewhere, but that ‘elsewhere’ remains contingent upon the beauty which attracted one in the first place (and which, in either context, can be sporadically re-verified by random ‘spot checks’). Not even those congenitally allergic to the cinema practised by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet are able to deny their unignorable visual mastery: the half-Euclidean, half-Blakean precision of their compositions; the controlled stillness or flux of movement within a given shot (the images of their films eschewing, as a result, the sort of pictorial plasticity that sets one dreamily measuring the screen for a frame); the preternatural ‘thereness’ of the humblest artefact (for the Straubs work on the principle that a filmed chair, let’s say, corresponds semantically to the word chair instead of to the three-dimensional object). Yet such metallic beauty (which, for now, I deliberately divest of any ‘meaning’ it might secrete) would appear to be incapable – in Britain, at least – of attracting an audience. It is judged arid, theoretical, dead. Worse than dead, ‘minimalist’. Why so?

It is with a certain bafflement that I pose the question, for their most recent feature, Klassenverhaltnisse or Class Relations (Artificial Eye), adapted from the incomplete and untitled comic novel by Kafka that is usually referred to as Amerika (reverberating with its author’s trademark k), strikes me as a great film – which is to say, a film like any other, except greater. And perhaps what is called for, as perverse as this may seem, is to have it reviewed like any other – in, or very nearly, the invent-orial, handily quoteful idiom of the populist press (“I found myself gripped from beginning to end…”, “Sensitively directed…”, “Immaculate performances all round…”, the near-mandatory “See it!”) – as though film criticism, often a case of making complex statements about simple works, might not on occasion consist of making simple statements about a complex work.

Let us run through it point by point, in the hope (one shared by those newspaper reviewers, I trust) that the film’s ‘feel’ will eventually be made tangible. What is complained of? For instance, that the Straubs’ camera tends to hang around after the departure of a character or characters from the shot, affectedly alerting us to a dim doorknob, it may be, or a blank brick wall. But what rule prescribes that I, the spectator, accompany the protagonist to the door? Am I his keeper or what? And why should a door just closed be any less generative of narrative suspense than one (in a horror movie) just about to be opened? To be sure, it is a contemplative form of suspense – the suspended, still pulsating, immobility of a space left vacant, of a trace. Like Bresson (whose L’Argent is the film Class Relations most resembles), the Straubs seem fascinated by such spectral traces; by, if you like, the Berkeleyan conundrum of what the world looks like, or whether it retains its existence at all, when no one except God (i.e. the camera) is perceiving it.

Then there is the problem of performance, of the notoriously zombielike Straubian delivery. It would be interesting to analyse the spoken ‘recitatives’ of Class Relations along strictly formal parameters of rhythm and musicality; or else, emancipated from the stale actorishness and sentimental rubato of what Barthes termed a ‘signaletic’ vocal art (one, that is, conveying the external signs of an emotion divorced from the emotion itself), as the authentic sound of Kafka. Why look so far, though? Crystallising the eerie, ceremonious passivity of Christian Heinisch as Karl Rossmann – an absence surrounded by presence, as some wag once denned a hole – is a throng of memorable minor characters, all of whom contrive to imprint themselves on the screen with instant, adamant aplomb. See for yourself: these performers act. (In fact, Mario Adorf, cast as Karl’s floridly nouveau riche immigrant uncle, may even be hamming it up a bit.) And whichever of the Straubs guided Libgart Schwarz, as the pallid, worn-out secretary Theres, interrupting her litany of afflictions with a chillingly brusque giggle and recounting the grisly circumstances of her mother’s death in a haunting monotone, is a brilliant director of actors.

Yet, continues the complainant, the film is little else but a series of verbal exchanges. At a Berlin Festival press conference, when the Straubs were asked why their film had been burdened with such a passé-sounding title as Class Relations, they replied that Kafka’s novel abounded in them. True or not, the world represented in the film version is one of masters and servants, of officiously truculent figures of authority (not a thousand miles away from the cantankerous creatures encountered by Carroll’s Alice) and weary, Soutinesque grooms. With his straw boater, his snugly packed metal suitcase and an inexhaustible fund of slightly crazy dignity, Karl travels steerage across the American continent as though it were a solider Atlantic. And if his confrontations with the Establishment are indeed articulated through a succession of duologues (or, more often, triologues), the set-ups in which these are framed might be regarded as veritable paradigms of socio-economic structure. Karl, ‘the man who disappeared’ (one of Kafka’s projected titles for his novel), seldom shares the screen with his betters: being ‘the lost one’ (yet another ur-title), he constitutes, not quite the film’s off-screen space, but an invisible contre-champ. As for the ruling class, shielded by a sleek armoury of office desks and tables, its immediate subordinates upright at their side, the merest hint of a hierarchical revision prompts a corresponding rearrangement of the set-up. The Hotel Occidental’s Head Cook, for instance, kindliest of Karl’s interlocutors, pointedly stands in front of her chair as his apologist, but installs herself behind it when coerced at last into doubting his innocence. By the itemising accumulation of such anxiety-inducing niceties, Class Relations acquires the quality of a courtroom drama, in which poor, trodden-on Karl is always in the dock.

And, to forestall the next complaint, many of these exchanges are funny, if in a deadpan sort of way. The unsmiling yet handsome and somehow poignant Heinisch recalls Keaton at his most starchily dapper; while his misadventures with Robinson, Delamarche and the gross Brunelda, not to mention being pursued by two droll Keystone Kops (how the k’s recur), made me laugh, audibly.

In short, Straub and Huillet have filmed Kafka in unslavishly faithful fashion, with a serenity strangely belying the venerable controversy which still cramps the cinematic adaptation of classic texts. They filmed everything that had to be filmed; and what they omitted to film would have been (neo-logistically echoing the dour, dismissive connotation with which the word literature was tainted by Verlaine) mere ‘cinemature’. See it!

Lost and found: Beby re-inaugurates

Reported in Sight & Sound Summer 1987, pages 157-8

Of all the lost films in cinema history’s phantom filmography, the ‘lostest’, so to speak, at least ex aequo with the complete Greed, has always been Robert Bresson’s Les Affaires Publiques. Virtually none of the fragmentary traces by which other celebrated lost films have succeeded in fitfully living on in the cinephiliac imagination – published stills, filmographical documentation, reviews dating from the initial release period – have ever emerged to invest it with even a semblance of reality (though it did form the subject of an article by Roger Leenhardt, now available in his Chroniques de Cinéma). All one knew was its title (which has turned out to be inaccurate), its date of registration (1934), its running time (approximately twenty minutes) and – most startlingly in view of the director’s subsequent reputation – the fact that it was a comedy. Indeed, Bresson himself referred to it, with perhaps more than a soupçon of poker-faced malice, as “like Buster Keaton, only much, much worse.”

Well, as certain readers will no doubt be aware, Les Affaires Publiques has been found – a real achievement considering that the title on the can of film was Le Chancelier (The Chancellor) while that on the print itself was Beby Inaugure (Beby Inaugurates). The can was chanced on by a group of film historians rummaging through the chaotically stacked archives of the Cinematheque Française and its contents were run through a moviola. When they understood what they had discovered, however, the question immediately arose as to Bresson’s own potential reaction. Though he had lately expressed a desire to see the film once more, it was by no means inconceivable that – this desire having, against the odds, become a reality – he would wish to have it suppressed. In the event, he confounded such pessimism by professing to be wholly enchanted with its unexpected exhumation from the Cinematheque’s vaults.

And the film itself? What, one asks, does a burlesque comedy by Robert Bresson actually look like? The answer: A circus with a plot; a piece of filmic doggerel; a cartoon with live actors – and like a cartoon activated exclusively by energy. For all that there is frankly nothing in Beby Inaugure quite as memorable as the fact and the circumstances of its belated rediscovery, it is not just a curiosity, to be savoured solely for its rarity; and if scarcely the revelation that might have been hoped, it is very much better, funnier than Bresson’s self-contradictory description had led one to fear.

Beby is, in fact, the performer’s, not the character’s, name: that of a (now forgotten) clown whose inscription within the title conforms to a French tradition of personalising burlesque comedies – Max se marie, Chariot patineur, Jerry souffre-douleur, and so on. Bresson aside, the only conjurable names on the credits are Marcel Dalio in a quartet of roles (radio announcer, admiral, fireman and sculptor) and Jean Wiener, composer of the perky incidental music. As for the plot, if that is the correct word, it is indescribable, being nothing more than a sequence of gags centred on two adjacent republics, Crogandia and Miremia (shades of Duck Soup), a Miremian aviatrix whose monoplane crashes on Crogandian soil, the solemn inauguration of a statue by the frock-coated Crogandian Chancellor (Beby), and the no less solemn and no less snag-infested launching of a ship.

Actually, despite glimmerings of Duck Soup, The Navigator (in the semi-choreographed animation of inanimate objects) and Million Dollar Legs (in the quaint surreality of the situation), Bresson’s maybe insufficiently anarchic sense of humour comes closest to the human puppetry of Clair’s Le Dernier Milliardaire. That said, there are, amid some stillborn bubbles of wit, a small cluster of absolute knockout jokes. At the screening I attended (three of us in the Cinematheque editing-room peering at the imagery on a moviola – a tough test, therefore, for any comedy), the most audible chuckles were reserved for the scene in which Dalio, wearing his fireman’s helmet, orders his men to be ‘at ease’, whereupon the entire brigade sinks gratefully backwards on to a row of deckchairs; and a marvellously whimsical visual pun involving the statue, whose gaping mouth prompts the audience into a collective fit of uncontrollable yawning until it occurs to Beby simply to close it, a trouvaille oddly evocative of another statue and the rather more ambiguous antics got up to by its mouth – that shown in Cocteau’s Le Sang d’un Poète. We laughed at these gags, I repeat, because they were funny, not because they had been devised by the creator of Pickpocket and L’Argent (which is, admittedly, a good joke in itself).

The ultimate question, though, one I have already been asked several times, must be: Seeing Beby Inaugure without foreknowledge of its auteur, is it possible to guess his identity? The film is a little jewel, sharply edited, on occasion felicitously composed, a delightful impromptu that is sort of perfect within its own tiny context – but no. Robert Bresson, one should after all be relieved to learn, has not missed his vocation.

See also

Introduction: Michael Brooke introduces our Gilbert Adair tribute trove (December 2011)

Early reviews: six of Adair’s early capsule reviews from the Monthly Film Bulletin (1979-80)

The rubicon and the rubik cube: Adair on exile, paradox and Raúl Ruiz (Winter 1981/82)

Memories of youth, anticipations of maturity: Adair’s reviews of La Luna and The Outsiders (Winter 1979-80 and Autumn 1983)

One elephant, two elephant: Adair’s reviews of That Sinking Feeling and Gregory’s Girl (Summer 1981)

Meandrous expeditions: Adair’s reviews of Stalker and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (Winter 1980/81 and Winter 1982/83)

Adair on music: reviews of Amadeus, Carmen and Ginger & Fred (Spring 1985, Spring 1986 and Monthly Film Bulletin March 1985)

The Nautilus and the nursery: Roland Barthes’s [sic] April-Fools paean to the Carry On cycle (Spring 1985)

Double takes: Heurtebise: Adair’s pseudonymous contributions to Sight & Sound’s Double Takes column (Winter 1984 to Summer 1985)

Gilbert Adair’s Top Ten films (September 2002)

The Dreamers reviewed by Ginette Vincendeau (February 2004)