The Gilbert Adair files

Meandrous expeditions

Editor’s note:

Andrei Tarkovsky and Steven Spielberg have little outwardly in common, but Adair admired both and wrote about each many times. It therefore seemed appropriate to pair the two, courtesy of these near-contemporary Sight & Sound reviews (although made in 1979, Stalker opened in Britain in 1981), both notionally science fiction but set in entirely recognisable earthbound milieux: the grim industrial backwaters of the Soviet Union, and Spielberg’s ‘suburban pastoral’ America. Present-day eyebrows may be raised at Adair’s repeated ‘E.T. as golliwog’ motif, an image that would already have been somewhat contentious even by 1982.

— Michael Brooke

Notes from the Underground: Stalker

Reviewed in Sight & Sound Winter 1980/1, pages 63-4

The narrative structure of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (Contemporary), as distinct from the meandrous expedition that occupies more than half its running time, is relatively, unexpectedly straightforward. The ‘stalker’ of the title (referred to by the English word throughout the film) is a guide who, for what is presumably a paltry fee, escorts two clients, a writer and a scientist, into an abandoned rural area named ‘the Zone’. Policed by armed guards in jeeps or on watchtowers, its sole inhabitants some lonely, haunted dogs and an occasional bird or fish, the Zone harbours at its centre a Room in which, it is claimed, one’s wishes are granted. How it has come to be invested with such a ‘gift’ is never explained, unless by a vague allusion to a meteorite that might have crashed there twenty years before (a conjecture possibly confirmed by the fact that the sparse flowers which have begun to bloom again have no scent); but its potential for sowing unrest is so feared by the state that the journey has to be undertaken clandestinely, with the most exquisite precaution.

Not that, once safely inside the region, the trio’s problems are over: though located no more than a few hundred yards from the Zone’s border, the Room would appear to be surrounded by a labyrinth of invisible – perhaps even, in a literal sense, immaterial – booby-traps, which only the stalker, possessed of mediumistic powers, is capable of negotiating without mishap. In the end, the scientist, denouncing the false hopes the Room must encourage, toys with the notion of blowing it up, while the writer, who had sought to spur his flagging creativity, contemptuously declines even to formulate a wish. To the wretched, by now half-demented stalker is left the Sisyphian task of sustaining a doubtful faith of which he is a humble priest but without which he is nothing.

An allegory, of course. Except that, where in most allegories the subject is displaced to allow the object to emerge to greater effect, Tarkovsky, with truly heroic deviousness, eliminates the genre’s random factor (eg, the orchestra as microcosm in Fellini’s Prova d’Orchestra) by setting Stalker not, as one would expect (as his Soviet masters doubtless expected), in an undefined mythical country, even less in the ‘America’ of the original novel, but, astonishingly, in the Soviet Union itself. Or rather (and this surely constitutes a first for contemporary Russian cinema), in nothing less than his own personal vision of the Soviet Union – a vision untrammelled by the precepts of socialist realism, unquestionably biased, yet riveting in its ferocity and pessimism. With this film, Tarkovsky re-entrusts to the medium a responsibility which in the West is upheld, if at all, only by documentaries (and by a rare maverick work like Pasolini’s Salò): that of testifying, of showing. (And, as always, it’s the films which show that are prevented from being shown.)

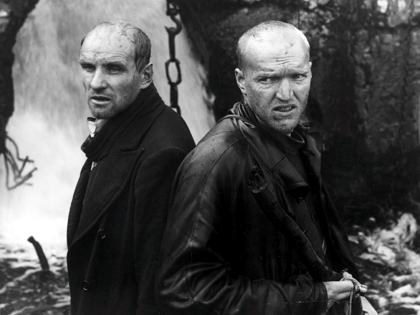

What we are given to see, in a preternaturally vivid style rendered Dostoevskyan by monochrome photography whose raspingly harsh textures suggest some grainy newsreel footage of the future, is a terrifying gallery of icons familiar from Solzhenitsyn and exploited – often to dubious ends – by the West but, till now, rigorously expunged from Soviet screens (and still likely to be projected only outside Russia). The stalker (an achingly tormented performance by Alexander Kaidanovsky), whose shaven head and filthy, ill-fitting clothes seem clearly to denote the political prisoner, and his two companions, disillusioned intellectuals both, enter the Zone with the weary stealth of refugees; and, earlier, in the window of the stalker’s bare apartment, is framed a vision not of Hell, but of earth circa 1980: the jagged, sooty silhouette of a factory disgorging its putrid fumes on to the sky and urinating unconcernedly into an oily, iridescent river. Such is the power of these filmic notes from the Gulag, the dissident underground and the ravages of ‘ordinary Communism’ that it matters less that they have been co-opted into allegorical science-fiction than that they are there at all, for the first time, on the screen.

Most disheartening, however, is the fact that the Zone, when finally breached, presents a scarcely more sanguine picture (one which is ironically emphasised by the film’s belated conversion to colour). Whatever its thaumaturgical properties (at one point, the grass is seen gently to undulate), this post-nuclear landscape is, to put it bluntly, a dump, the Room a twin to that in the stalker’s hovel. Vistas that had loomed green and inviting on the horizon turn out to be overrun by industrial detritus, and a lengthy pan along a polluted river bed uncovers an ugly trove of old coins, rusty metal pipes and, oddly, a syringe. Suddenly we find ourselves on no less shifting ground than the principals, as our perception of the Room’s authenticity is simultaneously strengthened and undermined.

For whereas Tarkovsky’s camera scrupulously respects the Zone’s fantastical topography (panning in such a way as to confound our expectations of where the actors stand in relation to the terrain, framing the stalker’s oval face upside down as it slowly rises from the river’s edge like an obscene sting ray), the two trespassers do succeed in defying its laws at no apparent risk to themselves. (Wilfully, as when the writer, in a fit of impatience, takes a taboo direct route, and fortuitously, as when the scientist, having lost his way, is later discovered peacefully munching sandwiches and drinking tea from a thermos flask.) And we remember then how, despite bullets buzzing around them and glimpses of sinister frontier guards, the legendary difficulty of access to the Zone had already seemed almost a contrivance, a pretence of barring entry (when in reality a select few were being ‘permitted’ it) by which the state could perhaps foster the useful illusion of limited but just attainable freedom.

If I have concentrated on the film’s visuals, it’s because the philosophical debate engaged in by the three men on the threshold of the Room, concerning both the fragility of faith and its insidious authority, seems to me much its weakest element, as if even Tarkovsky had been frustrated by what, in the Soviet context, still can or cannot be said and had reverted to the kind of banal generalities of professional ethics versus cynicism, and humanistic idealisation of art (“unselfish compared to all other human activities,” says the writer) to be found in cautiously ‘subversive’ East European films, notably Zanussi’s. More moving because more concrete is the direct interjection to the camera by the stalker’s long-suffering wife, speaking sadly but quite matter-of-factly about their hardships together.

Though allegories are traditionally multilayered, there is usually one layer which, like a forced playing-card, subtly imposes itself. In Stalker, that particular one is, I believe, specifically political and hardly needs to be spelt out. In any case, given Tarkovsky’s unique position (and one is dying to know the precise nature of the modus operandi arrived at between him and the Soviet establishment), the Western critic should learn to be as discreet as if he were reviewing a whodunit.

E.T. cetera: E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial

Reviewed in Sight & Sound Winter 1982/83, page 63

Several years ago, the BBC screened an imported American situation comedy series entitled Bewitched. It starred Elizabeth Montgomery, Dick York and Agnes Moorehead, and chronicled the misadventures of a middle-class junior executive type who had unwittingly married a witch. Aside from one episode which has stubbornly lodged itself in my memory, it was, as I recall, a feeble, undistinguished show. The episode I refer to centred around a prodigious, though mass-produced, doll or puppet or golliwog which, merely when touched, induced in its handler an ineffable, incommunicable sense of well-being. E.T. is just such a golliwog.

Critics would come back from last year’s Cannes festival, where the movie received its world premiere, critics of every conceivable theoretical cast, and they would brief you on the Antonioni, the Godard, Syberberg’s Parsifal and that intriguing little Rumanian film in the marché… and when in conclusion, just for a laugh, you enquired almost shamefacedly about Spielberg’s E.T. (UIP) an amazing transformation would occur. Our critic would go all soft, boneless, limp as a rag. He might even emit an audible coo, like a doting relative peering into a newborn’s cot. Robert Kramer, than whom it would be hard to name a director with a sensibility less attuned to Spielberg’s, feelingly described in an interview his wonderment, a wonderment at first reluctantly assumed, at the film’s capacity to generate happiness. And this – not its unprecedented commercial success, allegedly enriching Spielberg to the tune of $lm a day, not the $750m lawsuit brought against him for plagiarism (a grotesque claim, on the face of it, since anyone who has ever improvised a bedtime story for a child might consider himself as justified in suing), not the ubiquitous dolls, Christmas cards, teeshirts and cute bars of soap – is the real E.T. phenomenon.

However, like the golliwog in Bewitched, like the ineffable in general, it defies criticism. No, let me rephrase that: E.T. can of course be criticised, indeed it all but invites an unholy alliance of impressionistic, genre, sociological, auteurist and structuralist analyses. Except that, as we are dealing with a film to which one shamelessly capitulates, or does not, which draws laughter and tears as ‘naturally’ as hot and cold water can be drawn from the corresponding taps, or does not, subjecting it to a close analysis would be like performing upon it the same operation as threatens E.T. himself. Comparisons with Peter Pan, though apt, do not go nearly far enough. Barrie’s masterpiece, like all deeply felt expressions of nostalgia, is shot through with remorse, regret and melancholy (which in this case, as we know, concealed an acute sexual self-loathing). E.T., on the other hand, might be said to have been directed by Peter Pan. Since Spielberg has contrived to preserve intact, and without that sense of alienation from which Barrie suffered, a genuinely child-like idealism, the film’s dominant mode of ‘suburban pastoral’, exemplified by the magical shot of a Los Angeles street corner criss-crossed by Halloween night apparitions, reflects what is clearly a lived experience, one uncontaminated by wistfulness. Rather than Peter Pan, the work it evokes (bearing in mind that children these days, from whatever age group, are infinitely more sophisticated than their Edwardian predecessors) is Daisy Ashford’s The Young Visiters, prefaced by Barrie and written by its precocious authoress at the age of six. Now what purpose could possibly be served by analysing Daisy Ashford?

Yet, however sceptical as to the ultimate value of such an exercise, I have after all been commissioned to review E.T. What is there to say? Well, one might mention Spielberg’s version of the ‘other’ – here a benign, angelically sexless creature, whose visitation incorporates elements from the iconographies of the Annunciation and the Nativity; who, though capable of performing miracles, nevertheless remains dependent upon human protection from human aggression; who ‘dies’ only to be resurrected; and whose physical appearance suggests both the prematurely ageing astronaut in 2001 and the cosmic embryo into which he is metamorphosed. As already hinted at by the quasi-religious vibrations given off by Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Spielberg would seem to be groping towards a virtual theology of space, space as Heaven, offering solace to a world which has foolishly renounced its traditional God but still aches to extend its own spiritual frontiers. Which means, now purely in genre terms, that he can dispense with the cumbersome hardware of more ‘naturalistic’ science fiction. E.T.’s spacecraft resembles nothing so much as the flying saucer of comic strip convention, while the whimsical contraption he rigs up so as to beam an sos message back to his native planet would have struck one as perfunctory in a Méliès short. In fact, save for its ludic applications, technology is made the exclusive preserve of what, in E.T., subsists of the malignant ‘other’: the adult. Etc. (This could go on for pages.)

For the critic whose forte is the localising of sources and influences, E.T. is an echo chamber of allusive reverberations: from Disney, of course, particularly in the nocturnal sequences with which it opens and whose visuals are as densely animated as a 30s cartoon; from classic fairy tales, with the boy Elliott, for example, luring his newly befriended Hop o’ my Thumb to safety along a spoor of Smarties instead of breadcrumbs; from Hue and Cry and Emil and the Detectives, other films in which children gleefully join forces to thwart injustice; from Hitchcock; from Spielberg’s own work, via a few not-so-private jokes. Etc.

As to the empiricist, crawling over the film’s surface like a fly on a table-top, he would doubtless note that, though enlivened by a number of brilliant sight gags (e.g. Elliott’s mystified dog padding behind E.T. in the kitchen, then abruptly switching to the wheedling, tail-wagging posture of pet with master when E.T. opens the refrigerator door), its narrative construction is sometimes surprisingly clumsy. Elliott’s empathetic affinity with E.T. (his name is also book-ended by E and T) is so cavalierly introduced that one spends most of the classroom scene, in which he becomes tipsy by remote control, endeavouring to work out just what is happening. Nor does Spielberg ever bother to devise a convincing physiological (or psychosomatic) reason for E.T.’s false death; and his resuscitation, when divested of its Biblical overtones, appears to be a case of taking twenty tear-sodden pages to kill off Little Nell, so to speak, and applying artificial respiration on the twenty-first. Then there is the —

But beside the film’s boundless, airy, galactic charm such flaws pale into insignificance. And I recall, euphoric on the bus home after the screening, thinking of another bus, this time on film, and a gnomic conversation in which a trio of passengers were engaged. “Qui est-ce donc qui s’amuse à tourner en dérision l’humanité?” the first passenger asked. “Oui, qui nous manoeuvre en douce?” the second piped up. Let us revise the answer. “E.T., probablement.”

See also

Introduction: Michael Brooke introduces our Gilbert Adair tribute trove (December 2011)

Early reviews: six of Adair’s early capsule reviews from the Monthly Film Bulletin (1979-80)

The rubicon and the rubik cube: Adair on exile, paradox and Raúl Ruiz (Winter 1981/82)

Memories of youth, anticipations of maturity: Adair’s reviews of La Luna and The Outsiders (Winter 1979-80 and Autumn 1983)

One elephant, two elephant: Adair’s reviews of That Sinking Feeling and Gregory’s Girl (Summer 1981)

Adair on music: reviews of Amadeus, Carmen and Ginger & Fred (Spring 1985, Spring 1986 and Monthly Film Bulletin March 1985)

The Nautilus and the nursery: Roland Barthes’s [sic] April-Fools paean to the Carry On cycle (Spring 1985)

Double takes: Heurtebise: Adair’s pseudonymous contributions to Sight & Sound’s Double Takes column (Winter 1984 to Summer 1985)

Favourites: select Adair celebrations of Jean Cocteau, Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet and Robert Bresson (Autumn 1981; Spring 1985; Summer 1987)

Gilbert Adair’s Top Ten films (September 2002)

The Dreamers reviewed by Ginette Vincendeau (February 2004)