Review / From the archives

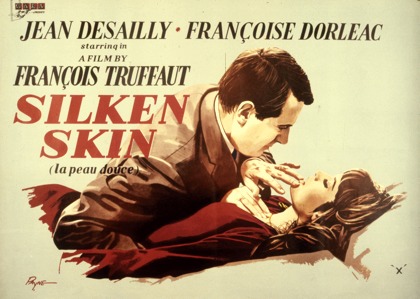

La Peau douce (Silken Skin)

‘Conventional’ on the surface, François Truffaut’s adultery drama hides deep seams of irony, melancholy and a newfound control, as Tom Milne argued in the December 1964 issue of the Monthly Film Bulletin

La Peau douce (Silken Skin)

France 1964

Director: François Truffaut

With Jean Desailly, Françoise Dorléac, Nelly Bénédetti

118 mins | Cert PG

Synopsis

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

Pierre Lachenay, aged 43, comfortably off, married and with a small daughter, runs a literary magazine in Paris. On a lecturing trip to Lisbon, he meets a young air hostess, Nicole, and has a brief but happy affair with her. Back in Paris again, and faced by his demanding, possessive wife, he discovers that Nicole has secretly given him her telephone number, so he rings her up. They meet several times, but she is nervous about letting him come to her flat, and they both find it squalid when they try and hotel. So he seizes the opportunity of a lecture at Reims to arrange to spend a couple of days with her in the country.

The need for concealment, which keeps Nicole hanging about while he fulfils his lecturing commitments, means that the weekend is not an unqualified success; and his wife, accidentally discovering that he had lied about the trip, begins to suspect his infidelity. Faced by her jealous rage, Pierre leaves her, determined to marry Nicole. A few days later he takes Nicole to see the flat he has chosen for them, but she is not interested in marriage, and walks out. Humiliated and alone, Pierre tries to ring his wife; but she, having just found proof of his infidelity, has already left for the restaurant where she knows he will be, and where she shoots him dead.

Review

To say that La Peau douce is conventional commercial filmmaking, as so many of its detractors have done, doesn’t take one very far. Truffaut’s tale of adultery may be conventional on the surface, but only on the surface. As the film begins, we see two hands clasping and unclasping behind the credit titles, in the casual embrace, perhaps, of two lovers in a cinema; and this image is the film’s own melancholy gloss on the tale it has to tell.

Pierre Lachenay is in search of love, but a love which will enclose all the tenderness and perfect harmony of the fairytale “and they lived happily ever afterwards”. But all he finds is the casual embrace, and this, perhaps, is all he can find in a world shattered by the bustle and tension of modern life. Nicole, the air hostess, can slip through Pierre’s fingers to the other side of the world in an instant; and their love is a fragmented affair, sandwiched between their other urgent preoccupations, and conducted in a world in the process of disintegration. Hence Truffaut’s persistent emphasis on images of disruption – gear changes in cars, lights being switched on and off – in a succession of extremely swift, choppy sequences. (It is worth noting that in Pierre’s one moment of untroubled joy, when he has just made his first date with Nicole, he switches on all the lights in his suite, thus achieving a kind of harmony.)

But not only is the love Pierre seeks impossible (or at least extremely rare), he is misled by the two women, who belie their appearance as well as the roles he has chosen for them: Nicole, as the mistress, should provide the passion, but she is cool and blonde, wears the white underclothes of purity, confesses that she can go for months without lovemaking, and at best can offer a passing tenderness; the wife, who should provide the understanding love, is dark and passionate, wears the black of sin, jangles fiercely on Pierre’s nerves, and reveals unfathomable reserves of physical love for him. At first glance the shooting at the end may seem to be out of key with the rest; but in fact, in a film which turns the usual routine of adultery upside-down, making the wife not only the injured party but the agent provocateur, it is not only just but right that it should end in a crime passionel.

It would be wrong, however, to suggest, that La Peau douce is a solemn film, for it is full of characteristic Truffaut touches of charm and humour; particularly effective is the very funny sequence at Reims, with Pierre racing from lecture room to hotel and back again, dashing by the way into a half-closed shop to buy stockings for his mistress, and then desperately trying to shake off his host while Nicole hovers crossly in the street outside, pestered by a lecherous passer-by. In some of Truffaut’s earlier work the charm was often stretched so far that it sat up and begged for admiration; here his control is almost perfect.

Tom Milne, Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1964

‘La Peau Douce’ is re-released around the UK from 4 February as part of the BFI’s François Truffaut retrospective at the BFI Southbank

See also

Sight & Sound’s top five film books (June 2010)

The New Wave at 50: The star reborn: Ginette Vincendeau on how the French New Wave transformed the nature of film stardom (May 2009)

The New Wave at 50: Riding the wave: six renowned directors describe what the New Wave meant to them (May 2009)

Radical chic: Chris Dark on Cannes’ hidden political tradition (June 2007)

Theatre of complicity: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith on the hidden artistry of Catherine Deneuve, France’s most beguiling enigma (May 2006)

Under the influence: Robin Buss explores Hitchcock’s influence on Dominik Moll’s Lemming and French filmmakers generally (April 2005)

Paris match: Godard and Cahiers: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith on the post-war Parisian fun and ferment that produced the New Wave (April 2001)

The Innovators 1950-1960: Divining the real: Peter Matthews calls for the rehabilitation of André Bazin, the high priest of realism (August 1999)

Looking at the rubber duck: Nicolas Roeg on François Truffaut (Winter 1984/85)