Review / From the archives

Taxi zum Klo

Frank Ripploh’s groundbreaking (self-)portrait of a gay teacher and errant lover is both impish and assured, wrote Bill Marshall in his 1982 Monthly Film Bulletin review

Taxi zum Klo

UK 1981

Director: Frank Ripploh

With Frank Ripploh, Bernd Broaderup, Orpha Termin, Dieter Godde

118 mins | Cert 18

Synopsis

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

Frank is a 31-year-old gay teacher living in Berlin. The pattern of his life and personality unfolds in a series of incidents, including his farcically locking himself out of his flat while naked, flirting with a garage attendant on his way to work, his popularity with both his pupils and his colleagues, and his casual pick-ups in public toilets. He takes cinema manager Bernd home for the night, but their love-making is interrupted by a distraught woman seeking refuge. They comfort her and, on Bernd’s insistence, she stays in the flat before going to a refuge house. As their relationship develops, Bernd moves in with Frank, but his dreams of fidelity and domestic stability in the country are undermined when he returns home to find Frank with another man. Entertaining Frank’s transvestite friend Wally for tea, they project the film Christian and his Stamp Collector Friend, used in school to show the horrors of homosexuality.

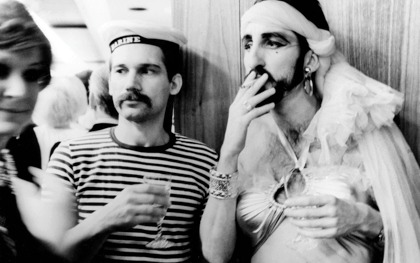

Frank has to spend several weeks in hospital after contracting hepatitis from a pick-up, but manages to sneak out and takes a taxi to various ‘cottages’; Bernd meanwhile plans on cementing their relationship with a holiday in the sun. The two quarrel one evening about their differing life-styles, and Frank continues to cruise. At a big fancy-dress ball, dressed as an Oriental princess, Frank flirts with a stable boy. In the morning, he and Bernd split up in the subway. Arriving at school in his costume, Frank soon has his class in a riot. A caption reveals that Bernd and Frank got together again, that Frank lost his job and became a filmmaker.

Review

Taxi zum Klo is a largely autobiographical venture, with Frank Ripploh and his former lover Bernd Broaderup reproducing their real-life situation. After a 1978 article in Stern in which he openly admitted to his homosexuality, Ripploh left teaching when disciplinary action was taken against him, and devoted himself full-time to filmmaking. This, his first feature, was made on a shoestring but the result is a mature work, perfectly controlled and finely photographed. Its mainstay is an attention to detail rather than generalisation, whether it is the jar of vaseline next to the alarm clock, or the omnipresence of the media from TV morning exercises or Liberace to the taxi-driver’s lurid tabloid. This is the manner of the opening sequence, where the visual exploitation of the badges and postcards on Frank’s wall, overlaid with Ripploh’s pat autobiography, points to the multi-faceted and even contradictory portrayal which will follow.

This and the film’s maturity and lack of drama recall Sunday Bloody Sunday, which examined similar questions of fidelity and homosexuality but in a vastly different milieu. Similarly, the subject of a gay teacher and the film’s relentless realism – notably the night drives through the city – owe much to Nighthawks [Ron Peck, 1978]. But here the central situation goes deeper into the issues surrounding a loving relationship, and rather than plodding, the narrative rhythm varies between the gradual introduction of highly endearing characters and the irruption of a number of unashamed gags in which Ripploh’s comic talent is evident. Unlike the Peck/Hallam film, the sex scenes are explicit and vary from the tender (Bernd and Frank bathing and shampooing each other) to the brutal (sado-masochism with the garage attendant). Moreover, the relationship with the heterosexual world is not as self-conscious: there is no scene where Frank confesses and explains his homosexuality to a colleague – simply, for example, the conversation with Irmchen about relationships in general.

Confrontation is represented obliquely – the stable boy revealing that he would lose his job if his homosexuality were known, the mocking reaction of a woman passenger to Frank and Bernd in fancy-dress. This approach is true of the portrayal of politics as a whole – Frank deciding to go to the baths instead of a meeting on Chile, his amusement at a neo-Nazi on TV calling on homosexuals to be put in work-camps. The most sustained ‘political’ sequence is the projection of the anti-gay film – required viewing at Ripploh’s own school – which also reveals the director’s assurance in his medium: the film-within-the-film combines with the favourite device of the cross-cut (often to-ing and fro-ing between Bernd and Frank) to show how Frank in the other room is trying, not to seduce his pupil, but to get him to pay attention to the dictation. The ending is not schematic: Bernd hugging a lamb in the countryside is the ‘tender’, couple-oriented homosexual; Frank is restless, but he does love Bernd, and the revelation of their reconciliation implies that nothing is really resolved. But the film’s irony, though often self-directed, hints at the creatively subversive nature of the subject: when Frank ‘comes out’ to his pupils, the result is not a round of serious questioning but the manifestation of anarchic revolt.

Bill Marshall, Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1982

‘Taxi Zum Klo’ is re-released from 22 April 2011 at venues around the UK

See also

The pride and the passion: Brian Robinson on 25 years of the London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival (April 2011)

Impetuous streams: Armond White on Raging Sun, Raging Sky and Julian Hernandez’s trilogy of mythical sex epics (March 2010)

The Class: Laurent Cantet talks to Ginette Vincendeau about his Palme d’Or-winning portrait of an inner-city school (November 2008)

Tell it to the camera: B. Ruby Rich on Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation (April 2005)

Queer and present danger: B. Ruby Rich on the influence of the early 1990s New Queer Cinema on subsequent mainstream indies (March 2000)