The pride and the passion: 25 years of the London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival

After a groundbreaking quarter of a century, the LLGFF is still relevant, says programmer Brian Robinson

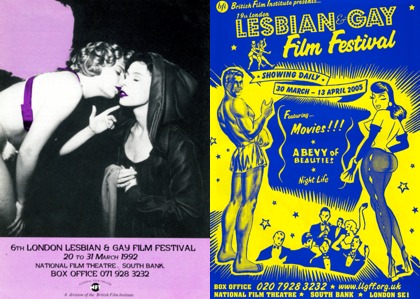

Going back to the start of the BFI London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival (LLGFF), which celebrates its 25th edition this year, takes us to 1986 – a world where paranoia about Aids and the government’s attempt to ban the promotion of homosexuality made the festival’s very existence a provocation to the prevailing zeitgeist. The idea itself goes back even further, however, to the founding of the Gay Liberation Front in Britain on 11 October 1970.

It was a gay-liberationist perspective that led Professor Richard Dyer of the University of Warwick to suggest a programme of gay films to parallel the work that had been done on women’s and black cinema at the BFI. More than 35 films, both contemporary and older, were shown at the National Film Theatre in the summer of 1977. Even questions by MPs over the validity of spending taxpayers’ money on ‘pornography’ failed to dent the event’s popularity.

Lesbians and gays had long found a fulfilling niche in film appreciation. Generations brought up on Cocteau, Visconti, Anger and Warhol knew that the cinema could bring pleasures and identifications outside the Hollywood mainstream. In film criticism, Parker Tyler’s writing had a resolutely queer inflection, while Robin Wood’s coming-out influenced his practice as a film critic so much that he changed his opinions and inscribed his sexuality on to his critical identity. In his essay ‘Responsibilities of a Gay Film Critic’ (originally delivered as a lecture at the NFT in 1976) Wood articulated his aim: “To contribute, in however modest a way, to the possibility of social revolution, along lines suggested by radical feminism, Marxism and gay liberation.”

The 1970s saw the growth of an appetite and audience for films with gay subjects, as the post-Stonewall generation created its own culture. Then in 1986 Mark Finch, a former student of Richard Dyer, convinced the NFT programmers to show a selection of nine films entitled ‘Gays’ Own Pictures’, based on an event at the Tyneside Film Festival.

The selection included Steve Buscemi’s acting debut Parting Glances, directed by Bill Sherwood, Donna Deitch’s Desert Hearts and Arthur Bressan’s Buddies, all of which remain classics of their genre. Dancing in Dulais, meanwhile, was a made-for-television account of an unlikely project in which a Welsh community in the grip of the Miners’ Strike was adopted by a group of left-wing activist lesbians and gay men.

This eclectic mixture of narrative, experiment and documentary remains the festival’s hallmark to this day. Looking back across its various editions, one is struck by the varied range of creativity on show, the gradual waning of the trope of the suicidal lonely queen, the increasing confidence of the communities reflected on screen and the increase in that once rarest of films, the lesbian narrative feature.

Inevitably, the impact of Aids is writ large across the programmes as filmmakers grappled to make sense of a devastating medical emergency. Rob Epstein and Peter Adair’s The Aids Show (1986), a vibrant agitprop video of an activist theatre project, was typical, as was Barbara Hammer’s Snow Job: The Media Hysteria of Aids (1986). Many filmmakers were themselves lost to Aids – to this day the great unspoken impact on queer cultural production. For a filmic take on this issue, watch David Weissman’s We Were Here, a brilliant and moving account of the Aids crisis in San Francisco that played at the Sundance and Berlin festivals and will feature in this year’s LLGFF.

In the 1980s there was a mere handful of gay film festivals; now there are over 180 worldwide. Notable pioneers were San Francisco’s Frameline, LA’s Outfest and Turin’s Da Sodoma a Hollywood. In 1992 Sundance elevated a generation of leading lesbian and gay filmmakers to public attention via its Barbed Wire Kisses panel, hosted by B. Ruby Rich. Its members – among them Isaac Julien, Todd Haynes, Gregg Araki, Gus Van Sant and Derek Jarman – are among the names who went on to define queer filmmaking. A seminal article by Rich, originally published in Village Voice, christened the movement when it was republished in Sight & Sound under the heading ‘New Queer Cinema’.

The Berlin Film Festival’s gay Teddy Award, also celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, has latterly been joined by initiatives at Venice (Queer Lion) and Cannes (Queer Palm). Previously, Europe’s A-list festivals (with the notable exception of Berlin) didn’t demonstrate much of an interest in gay films. But in recent years – with João Pedro Rodrigues’s O fantasma (Phantom, 2000) and John Cameron Mitchell’s Shortbus (2006) appearing at Venice, and Araki’s Kaboom (2010) at Cannes – there seems to be a new appetite for queer cinema. Anyone watching Gus Van Sant’s early diary films in 1986 would surely have been surprised to know that he would go on to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes for Elephant in 2003.

Out of the margins

So what does this mean for the future? Queer filmmakers may no longer be as marginalised as they once were, but audiences still need the chance to explore the coming generation of new voices, whose films reflect a diversity of interests and experiences that are still not part of the general vocabulary of cinema. True, one can follow the trajectory of a career like that of John Greyson – who was present at the festival with early shorts in 1987, and whose promise was more than fulfilled with the features Lilies (1996), Proteus (2003) and Fig Trees (2009). But for every Greyson or Araki, there are dozens of filmmakers who struggle.

Lesbian directors remain marginalised. There are exceptions: when Lisa Cholodenko’s High Art opened the LLGFF in 1999, few could have foreseen her receiving Oscar nominations for The Kids Are All Right. But how many other lesbians can you name who have made more than three narrative features?

Some distributors or directors resist having their films shown in a gay festival, worried that they will be labelled ‘gay films’. The marketing campaigns for A Single Man and Brokeback Mountain were object lessons in how to sell a gay film in a manner that would lure in the non-gay audience. However, the good news is that distributors increasingly enjoy the additional exposure and PR buzz that a gay festival can offer. Television and mainstream film distributors are generally not interested in a large part of the more provocative or challenging output of contemporary filmmakers, but there is a ready market for titles suitable for theatrical release or DVD.

The shocking fact remains, however, that a film as popular and widely seen as Parting Glances, released as recently as 1986, was in urgent need of restoration due to the lack of any surviving prints in distribution by the beginning of the 21st century – which gives an indication of the issue of access to queer cinema’s archives. The Outfest Legacy Project is an ongoing collaboration with the UCLA Film and Television Archives to rescue internationally important films of the queer canon, but it can only scrape the surface of what’s needed. Where are the DVD box-sets of John Greyson’s early work? And though Barbara Hammer will have a major retrospective at Tate Modern in 2012, there are dozens of her celluloid sisters who deserve another look.

The glory of the LLGFF, and one of the most important reasons for its existence, is discovery: exposing unknown independent filmmakers who have the cinematic intelligence to tell new stories in fresh ways – and celebrate sexual diversity. The existence of YouTube, Graham Norton and gay storylines in soap opera doesn’t remove the need for a festival like the LLGFF; if anything, with the technological and cultural explosion of image-making, we’re now in even greater need of a filter for big-screen work.

Xavier Dolan’s I Killed My Mother (J’ai tué ma mère, 2009) is an interesting example of a film that might previously only have been seen at a gay film festival, but played at Cannes and Toronto, as well as at last year’s LLGFF. His follow-up Heartbeats (Les Amours imaginaries) was also selected for Cannes in 2010 – a remarkable achievement for a 21-year-old filmmaker.

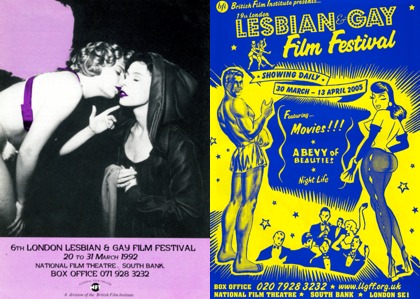

Although this year’s LLGFF has been constrained by budget cuts, and has consequently been shortened to a week, it still boasts more than 35 features, including a strong showing for UK films and world premieres from rising stars, such as Kanchi Wichman’s Break My Fall and Mark Harriott and Mike Matthews’s Unhappy Birthday.

Born out of radical activism, now courted by corporate sponsors, the LLGFF can, I hope, continue to adapt – while also continuing to showcase contemporary and earlier queer cinema to a new generation, engage with new debates and enhance the lives of viewers, regardless of sexual preference.

The 25th London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival runs 31 March–6 April 2011

See also

The Kids Are All Right reviewed by Sophie Mayer (November 2010)

Queen of Hollywood: Sophie Mayer on Hollywood’s pioneering director Dorothy Arzner (March 2010)

Impetuous streams: Armond White on Julian Hernandez’s trilogy of mythical sex epics (March 2010)

Roll forever: Gus van Sant on Andy Warhol’s persisting influence on cinema (August 2007)

The lost leader: Colin MacCabe on the missing influence of Derek Jarman in British cinema (January 2007)

Lonesome cowboys: Roger Clarke on Brokeback Mountain (January 2006)

Tell it to the camera: B. Ruby Rich on Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation (April 2005)

Gerry reviewed by Ryan Gilbey (October 2003)

Magnificent obsession: Richard Falcon on Todd Haynes’ Far from Heaven (March 2003)

But I’m beautiful: Andy Medhurst proposes Muriel’s Wedding as one of the best films of all time (July 2002)

Queer and present danger: B. Ruby Rich on the influence of the early 1990s New Queer Cinema on subsequent mainstream indies (March 2000)

High Art reviewed by Leslie Felperin (April 1999)

Psycho (van Sant) reviewed by Gavin Smith (February 1998)