Close up / From the archives

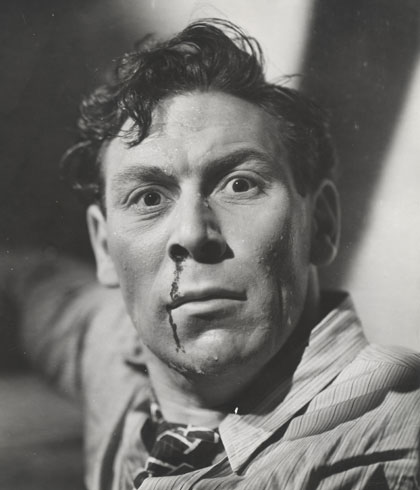

Murder in Reverse?

John Slater in Montgomery Tully’s Murder in Reverse?

Cathi Unsworth finds that despite some dated stylistic hiccups William Hartnell’s lead performance still gives ‘Murder in Reverse?’ a tough authenticity

“KILLER FINDS CORPSE ALIVE AFTER 15 YEARS!”

As a newspaper headline, even a congenitally accident-prone reporter like Peter Rogers (Jimmy Hanley) couldn’t fail to shift issues with it. As a plot twist to a post-war British thriller competing against Hollywood’s golden age of film noir it’s a fiendish premise. And it needed to be. Montgomery Tully’s debut Murder in Reverse? (1945) has to struggle against more than a modest budget to create the atmosphere of menace the Irish director clearly desired. It has to cope with the goofy odd couple of Hanley and Dinah Sheridan doing an awfully-awfully romantic-comedy routine slap bang in the middle of what clearly would have preferred to be an icy slab of hardboiled fiction.

No doubt this was what the producers felt they required to lure their faithful female audience into cinema seats, but thankfully Tully, who also wrote the script, had a couple of a secret weapons to deploy: an eye for telling detail in the Docklands saloon bars and dingy bedrooms where the story’s treachery and duplicity play out; and William Hartnell in the lead role.

The film begins in Fleet Street offices of the Daily Examiner, where editor ‘GS’ Sullivan (Brefni O’Rorke) has a story he wants chasing, but unfortunately the only reporter he has to hand is clueless cub Rogers, a Wodehousian toff who has already caused him “two libel actions, one prosecution for defamation of character and the best advertising account in the business”.

Snapping out orders between having a suit fitted and a call from the Home Office, GS comes across as a worldly hack who has hoofed his way to the top, while the Examiner’s palatial art deco office mirrors the Daily Mail’s former headquarters at Northcliffe House. Yet it soon becomes clear that GS is no Lord ‘Hats off to the Blackshirts!’ Rothermere. Rather, his stern exterior belies a softer heart, exposed as he recalls the scoop that made his name back in 1930: of stevedore Tom Masterick (Hartnell) and his love rival Fred Smith (John Slater).

Chili Bouchier and William Hartnell

Witnessed in flashback, Tom is the only person on his cobbled street unaware that his glamorous wife Doris (Chili Bouchier) is carrying on behind his back, despite her polka-dot suit, high heels and lashings of lipstick, supposedly applied for a night out at the talkies with her neighbour Mrs Moore (Maire O’Neill). Even his young daughter Jill (Petula Clarke) inadvertently reveals as much when she says that her poor performance at maths in school was down to him “not being able to put two and two together”. Only when the same Mrs Moore appears on his doorstep a few minutes after Doris has left, claiming not to have seen her all day, do the cogs slowly begin to whirr in Tom’s brain.

When Doris returns with another tall tale, Tom finds Limehouse lothario Fred Smith loitering on his doorstep. Spivvy Fred taunts Tom with quips about his missus and continues to provoke him on the docks the next day. Returning home to find a ‘Dear John’ letter and Doris departed, Tom is directed to the North Star public house by the all-knowing Mrs Moore.

“You might be doing the gardening Tom,” she tells him. “But someone else is picking all the plums.”

Hartnell and John Slater

Tom confronts his errant wife and her lover in an epic, sprawling pub fight, made all the more authentic by the nonchalance of the bar staff, who continue to polish glasses while Tom and Fred slug it out all over the shop and the customers retreat muttering to the edge of the room. The landlord (Scott Sanders) only becomes concerned when Tom reaches for the huge scimitar that is hanging on the wall and proceeds to chase Fred through the darkened wharves and up to the top of his crane. When his rival screams and plunges into the Thames, we cannot see whether the flash of the sword in Tom’s hand has actually delivered a killer blow.

But the locals are quick to make their own minds up and after a storm of gossip has brewed, Tom is driven away by the police, apparently bewildered by the whole affair and loudly protesting his innocence. From the back of the patrol car, he spots a ship called the Chichester and shouts that he can see Fred aboard the deck, a claim that is not backed up by the camera.

Needless to say, nobody believes him.

Soon Tom is in the dock of the Old Bailey, facing Kenneth Crossley QC (a lugubrious Kynaston Reeves), while in an inspired intersection of cut-away scenes he simultaneously receives the wisdom of the court of public opinion in the North Star – including the landlord, now bragging about the role of his sword in the drama.

Directed by the cross-examinations of Crossley, the jury find Tom guilty. Gripping the rail of the dock in a film of cold sweat, his saucer eyes dilated with the fear of a cornered beast, he cries out: “I am innocent! Lies, lies! Words, words!”

Hartnell, Dinah Sheridan and Brefni O’Rorke

Back in the present, GS explains to Rogers that a campaign for clemency led by the Examiner spared Masterick the noose and that today he is finally being released from Dartmoor. “Get down to Paddington and meet him off his train,” he commands. “Offer him a hundred pounds for his story.”

Showing some initiative at last, Rogers ponders the whereabouts of Tom’s daughter Jill these past 15 years. Informing him that “she was fostered by a respectable family”, a bridling GS orders him to drop the subject. We soon find out why. While Rogers hangs pointlessly around at the train station, Tom Masterick is already in GS’s office. He asks the editor how his daughter is and whether he may be permitted to see her – for little Pet has now grown up into shapely Sheridan, who confounds her adopted daddy’s plans to keep her from her real father by swanning into his office on cue to demand some pocket money. Despite being unaware of Tom’s identity, Jill feels an affinity to the “nice old man”, and a collision course is set that will see Tom striving to clear his name.

As convicted murderer Tom Hartnell conveys with twitching-eyed verisimilitude a man with a suppressed powder keg inside him, charting with superb ambiguity his character’s progress from the good-hearted family man who is cuckolded to, emerges 15 years later and after a chain of catastrophic events, a hardened old lag with revenge on his mind. In the film’s confrontational scenes, Tully proved that in Hartnell he had his equivalent of James Coburn: an actor who could convey so much with just the slightest of gestures. Tormented Tom Masterick is a part that the actor clearly relished, burning the rest of the cast off the screen with the intensity he brings.

William Hartnell (third from right) on the set of Brighton Rock

Murder in Reverse? was the beginning of Hartnell’s filmic golden years. Following service in the Tank Corps in World War II, the actor had only just made the transition from the light roles he had played before the conflict with his portrayal of Sergeant Ned Fletcher in Carol Reed’s 1944 war drama The Way Ahead. From then until the time he was hijacked by a TARDIS in 1963, he would enjoy a string of roles in which he would excel as a hardbitten policeman, street gangster or tough guy – most notably that of the whispering thug Dallow in John Boulting’s 1947 classic Brighton Rock.

Similarly, Tully would stick to the hardboiled path, directing noir films such as 36 Hours (1953) and The Glass Cage (1955) for Hammer, and the television series The Edgar Wallace Mysteries, Man from Interpol and Fabian of the Yard.

For Hartnell, who had run with gangs in his impoverished youth in 1920s Kings Cross and found his way out of a life of petty crime through the boxing gym and then the theatre, the milieu of Tom Masterick’s Limehouse cannot have been a hard stretch of the imagination. However hard to swallow some of Murder in Reverse? may seem today, it is Hartnell who draws the eye and holds our belief in his part right to the last scene.

‘Murder in Reverse?’ screens on 22 June in the Projecting the Archive / Capital Tales strand at the BFI Southbank, London

Cathi Unsworth is a journalist, editor of the anthology ‘London Noir’ (2006) and author of ‘The Not Knowing’ (2005), ‘The Singer’ (2007) and ‘Bad Penny Blues’ (2010) (all Serpent’s Tail).

See also

Lost and forgotten: Mark Sinker on the ‘forgotten’ watershed films of the 1970s (July 2010)

Bloody Yorkshire: Nick James on the Red Riding trilogy (March 2009)

I’ll Sleep When I'm Dead reviewed by Ryan Gilbey (Film of the Month, May 2004)

Eager beaver: Richard Attenborough interviewed by Geoffrey Macnab (September 2003)

Odd man out: Kevin Jackson on David Cronenberg’s Spider (January 2003)

Get smarter: Danny Leigh on a new breed of nostalgic, unreal British gangster movie (June 2000)