Odd Man Out

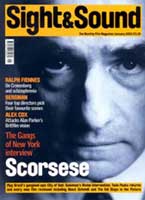

In Spider a master of the cool macabre directs one of the UK's finest actors in a portrait of a delusional misfit. Kevin Jackson talks to David Cronenberg and Nick James meets star Ralph Fiennes.

Close your eyes, relax, try to think of the characteristic look and feel of a David Cronenberg film. The first thing that comes to mind will probably be... well, let's be honest, it will probably be cherry-red gore or glop, vile, amorphous masses of mucoid substance yanked, blasted or secreted into daylight from deep inside the body cavity of some hapless mutilated person or ghastly thing. Now, dispose gently of this particular idée reçue and think again. This time the image most likely to emerge is one of a curiously ominous, portentous quality of light, a high-contrast sheen playing with unsettling delicacy over smooth surfaces of metal, glass or all-too-vulnerable flesh. The total effect is coolly, not to say chillingly, elegant, and has been acknowledged as a signature by the director's fans and detractors alike.

On the face of it Cronenberg's new film Spider appears to be bathed in a radically different kind of light - to be every bit as distinct in visual style from his usual form as it is in location and content. Adapted from a well-received novel by Patrick McGrath, Spider is the Canadian director's first venture into unadulterated English subject matter - no Crash-style relocations to North America this time round. Its eponymous protagonist, played by Ralph Fiennes, is a recently discharged mental patient, gaunt and aggressively timid, relocated to a slummy half-way house in the depths of London's East End run by one Mrs Wilkinson (Lynn Redgrave). In solitary, silent walks and nocturnal fantasies, Spider attempts to recreate the violent events from his boyhood that led to his confinement. These involve memories of his turbulent, pub-loving father Bill Cleg (Gabriel Byrne), his saintly mother Mrs Cleg, and Yvonne, the pub tart who eventually replaces her (both roles are played by Miranda Richardson).

This, plainly, is a very different milieu from those of the numbed bourgeoisie of Crash (1996), the sickly overachieving professionals of Dead Ringers (1988) or M. Butterfly (1993), or the glamorous techno-adventurers of eXistenZ (1999). Where other Cronenberg films have dwelled on the pristine surfaces of cars, transportation pods or baroque gynaecological instruments, Spider gloats on filthy, nicotine-stained fingers, piles of bespittled dog-ends, blisters in the browning wallpaper, vats of lumpy off-white porridge, shirt collars grown black with years of sweat and muck.

It is, in short, unrelentingly shabby; and yet there remains something in the quality of these calculatedly sordid visions that is stubbornly Cronenbergian. It's a style that readily accommodates two extremes - precise notation of period detail (viewers of a certain age will wince in sympathy at the sight of a 'Bronco' toilet roll, notorious for its harshness to tender parts) and sheer subjective fantasy - passing through all points between. This mongrel method has its antecedents in certain schools of literature as well as film, and Spider - which might be thought of as the third of Cronenberg's 'literary' productions, following his adaptations of J.G. Ballard's Crash and William S. Burroughs' The Naked Lunch (1991) - is at times reminiscent of the work of playwrights and novelists loosely associated with mid-20th-century absurdism or existentialism. The film's milieu, I suggested to Cronenberg, is not too far from that of, say, Harold Pinter's The Caretaker, another miniaturised epic set in a grimy upstairs room and featuring a man recently discharged from an asylum.

Archetype of the artist

"I saw the movie of The Caretaker and loved it, but we were thinking more of the novels of Samuel Beckett - Molloy, Malone Dies - and even of the look of Beckett himself. Of course, we couldn't do the cheekbones, but there was the haircut and the body language and the image of Beckett in the streets of Paris, walking around with his notes."

"I was also thinking of Kafka and Dostoevsky, but while we were making the movie I never consciously realised that though it appears to be about murder and false or 'infected' memory, it's really also about art, about being an artist, and that Spider is a kind of artist. In the novel Spider writes the novel - the novel is his journal - and that means he's very literary, verbally adept, self-aware. Patrick McGrath in his first draft of the script had Spider writing in good English, and then voiceover, reading from the novel - the old trick. And my trick was to say, let's get rid of that. I said to Patrick, these are two different Spiders - the Spider you've created yourself for the cinema can't be the same Spider who's reading this stuff. It's a different voice."

"At that point I could also have said we needn't show the journal, show him writing in the notebook. But I felt we wanted something physical for Spider to do, to demonstrate his obsessiveness and his attempt to organise his thoughts and to bring his memories into some kind of alignment. So I suggested the journal would be in his own language - some kind of hieroglyphics - and I asked Ralph Fiennes to develop this type of cipher because I wanted him to feel comfortable writing it. And it wasn't until I was editing the movie that I thought, my God, this is the archetype of an artist, the nightmare version of an artist mumbling to himself incoherently in the streets and writing passionately and obsessively and with great attention to detail in a language that's incomprehensible to anybody else and maybe even to himself."

"I was very excited to shoot in England, and, as a Canadian, to get to grips with my sense of Englishness. I love English films of the 1930s and 1940s, for instance Carol Reed's Odd Man Out, and I had a real sense of the experience of those years as delivered through cinema. To connect with that - to challenge my ability to accurately connect with it - was part of the excitement. There was never any question of relocating to North America."

"There was also a timeless element which I was conscious of wanting to capture without being coy. We chose a period that was slightly different from the book - in the book it's closer to the war, but you have only a hint of that in the film with the back-to-back street being replaced by structures that would have been there as late as the 1960s. My usual production designer Carol Spier was busy doing Blade II in Prague so it meant working with someone new. Luckily I found Andrew Sanders, who was not only English but the right age - he'd lived through this."

No compromise

For the sixth time in a row Cronenberg called on the services of cinematographer Peter Suschitzky, whom he's used exclusively since Dead Ringers in 1988, establishing an exceptionally fertile working relationship. Cronenberg first encountered Suschitzky in a book called How It Happened Here, about Kevin Brownlow's 1963 film of almost the same name, made when the English director was barely out of secondary school and Suschitzky was just 22 - reportedly the youngest cameraman ever to have shot a British film.

"Then I started to look out for his work. He'd shot The Empire Strikes Back, which I thought was the only good-looking Star Wars movie - it's almost like an art movie in terms of its lighting, which is so unexpected in comparison with the first one. I saw a couple of other things and I just knew I liked his lighting sensibility. Then, of course, we met and got along very well, though he's a very different kind of person from me."

"By now we've developed a shorthand, so we can be incredibly efficient and yet compromise nothing in terms of taking the time to do things right. We both work in the same way, it's very intuitive, not analytical - we may see a few movies, refer to a few paintings, but we don't set out with the idea of a 'look' and we don't know what we're going to do when we set up for the first shot. In the case of Spider we looked at a lot of photographs and period footage but the only other movie we really had in mind was Roy Andersson's Songs from the Second Floor. We were looking at it for the lack of contrast, the lack of light versus dark. Usually Peter and I are very interested in contrasty film and we use a negative that will give good contrast. But here we felt that the murkiness and lack of definition a low-contrast filmstock would bring would replicate Spider's confusion and the lack of definition in his thought. So we used a low-contrast Fuji stock."

"We find we're still pushing each other. In this movie I tried to get Peter to do something that's very much against a cameraman's instinct - I told him I didn't care where the light came from, how realistic it was. For instance, there's a lamp sitting on Spider's bedside table but we never turn it on, even though it would be a nice source of light if you're worrying about the reality. There are moments when light is coming from a wall, a place that couldn't be a light source - at a certain point I began to realise we were making an expressionist film, in a quiet way. Even in terms of the choreography of the streets - I had all kinds of period cars and extras lined up in period costume but whenever we used them it felt totally wrong and finally we'd be left with Spider alone on the streets. There's never been a time when London has been so empty."

Spider, c'est moi

Cronenberg lists several reasons why he was willing to take on a project that might initially seem remote from his characteristic concerns. In practical terms it was an unusual aspect of the production package that first tempted him - Ralph Fiennes had asked his agency to affix a letter to the script underlining his willingness to play the part. Intellectually the director was intrigued by the theme of how memory can be cast and recast to make sense - often false sense - of present-day identity. But in emotional terms it was because the raw material of McGrath's novel spoke very intimately to some of his more anxious fantasies.

"Spider, c'est moi - I can easily see myself becoming Spider, whether because of a medical problem or a financial problem or an emotional trauma. It isn't an abstract feeling but a strong, visceral feeling that I can connect with this creature. I could see myself walking the streets muttering to myself and what I was saying would have meaning for me but for nobody else. When you say this some people think you're being cute, they don't believe you for a minute. But there was a French journalist, and I said to him, 'I am Spider', and he said, 'Well, who isn't?'"